Afternoon coffee time, but Al’s place is a little noisier than usual. “Hey, Sy, come here and settle this.”

“Settle what, Al? Hi, Vinnie.”

<waves magazine> “This NANOGrav thing, they claim it’s a brand‑new kind of gravity wave. What’s that about?”

“Does it really say, ‘gravity wave‘? Let me see that. … <sigh> Press release journalism at its finest. ‘Gravity waves’ and ‘gravitational waves’ are two entirely different things.”

“I kinda remember you wrote about that, but it was so long ago I forget how they’re different.”

“Gravity waves happen in a fluid, like air or the ocean. Some disturbance, like a heat spike or an underwater landslide, pushes part of the fluid upward relative to a center of gravity. Gravity acts to pull that part down again but in the meantime the fluid’s own internal forces spread the initial up‑shift outwards. Adjacent fluid segments pull each other up and down and that’s a gravity wave. The whole process keeps going until friction dissipates the energy.”

“Gravitational waves don’t do that?”

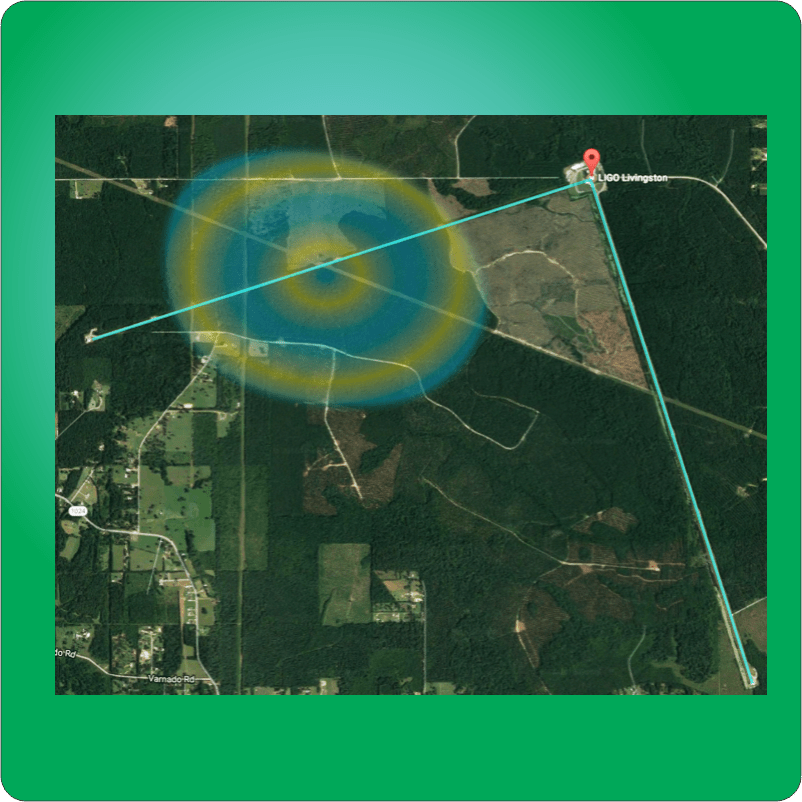

“No, because gravitational waves temporarily modify the shape of space itself. The center doesn’t go up and down, it…” <showing a file on Old Reliable> “Here, see for yourself what happens. It’s called quadrupolar distortion. Mind you, the effects are tiny percentagewise which is why the LIGO apparatus had to be built kilometer‑scale in order to measure sub‑femtometer variations. The LIGO engineers took serious precautions to prevent gravity waves from masquerading as gravitational waves.”

“Alright, so now we’ve almost got used to LIGO machines catching these waves from colliding black holes and such. How are NANOGrav waves different?”

“Is infrared light different from visible light?”

“The Hubble sees visible but the Webb sees infrared.”

“Figures you’d have that cold, Al. What I think Sy’s getting at is they’re both electromagnetic even though we only see one of them. You’re gonna say the same for these new gravitational waves, right, Sy?”

“Got it in one, Vinnie. There’s only one electromagnetic field in the Universe but lots of waves running through it. Visible light is about moving charge between energy levels in atoms or molecules which is how the visual proteins in our eyes pick it up. Infrared can’t excite electrons. It can only waggle molecule parts which is why we feel it as heat. Same way, there’s only one gravitational field but lots of waves running through it. The LIGO devices are tuned to pick up drastic changes like the <ahem> massive energy release from a black hole collision.”

“You said ‘tuned‘. Gravitational waves got frequencies?”

“Sure. And just like light, high frequencies reflect high‑energy processes. LIGO detects waves in the kilohertz range, thousands of peaks per second. NANOGrav’s detection range is sub‑nanohertz, where one cycle can take years to complete. Amazingly low energy.”

“How can they detect anything that slow?”

“With really good clocks and a great deal of patience. The new reports are based on fifteen years of data, half a billion seconds counted out in nanoseconds.”

“Hey, wait a minute. LIGO’s only half‑a‑dozen years old. Where’d they get the extra data from, the future?”

“Of course not. Do you remember us working out how LIGO works? The center sends out a laser pulse along two perpendicular arms, then compares the two travel times when the pulse is reflected back. Light’s distance‑per‑time is constant, right? When a passing gravitational wave squeezes space along one arm, the pulse in that arm completes its round trip faster. The two times don’t match any more and everyone gets excited.”

“Sounds familiar.”

“Good. NANOGrav also uses a timing‑based strategy, but it depends on pulsars instead of lasers. Before you ask, a pulsar is a rotating neutron star that blasts a beam of electromagnetic radiation. What makes it a pulsar is that the beam points away from the rotation axis. We only catch a pulse when the beam points straight at us like a lighthouse or airport beacon. Radio and X‑ray observatories have been watching these beasts for half a century but it’s only in the past 15 years that our clocks have gotten good enough to register timing hiccups when a gravitational wave passes between us and a pulsar.”

~ Rich Olcott