“Hey, Uncle Sy, I’ve got a what‑if for you.”

“What’s that, Teena?”

“Suppose we switched Earth’s air molecules with helium. No, wait, except for the oxygen molecules. I know we need them.”

“First off, a helium-oxygen atmosphere wouldn’t last very long, not on the geological time scale. That’s an unstable situation.”

“Why, would the helium burn up like I’ve seen hydrogen do?”

“No, helium doesn’t burn. Helium atoms are smug. They’re happy with exactly the electrons they have. They don’t give, take or share electrons with oxygen or anything else. No, the issue is that helium’s so light.”

“What difference does that make?”

“The oxygen and helium won’t stay mixed together.”

“The air’s oxygen and nitrogen molecules are all mixed together. They told us that in Science class.”

“That’s correct. But oxygen and nitrogen molecules weigh nearly the same. It would take eight balloon‑fulls of helium to match the weight of one balloon‑full of oxygens. Suppose you had a bunch of equal‑weighted marbles, say red ones and blue ones. Pretend you pour them into a big bucket and stir them around like an atmosphere does. Which color would wind up on top?”

“Both, they’d stay mixed together.”

“Uh-huh. Now replace the blue marbles with marble‑sized ping‑pong balls and stir well.”

“The heavy marbles slide to the bottom. The light balls need to be somewhere so they get bullied up to the top.”

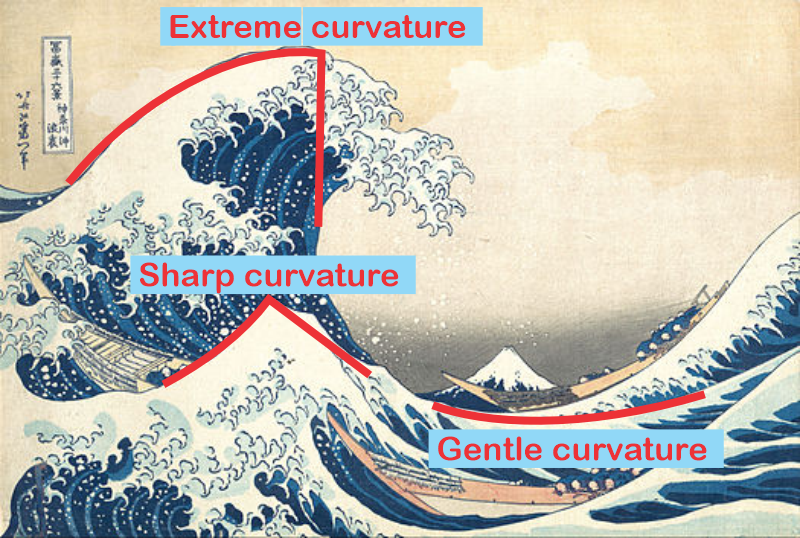

“Exactly. That’s what the oxygen molecules would do — sink down toward the ground and shove the helium atoms up to the top of the atmosphere. Funny thing though — the shoving happens faster than the sinking.”

“Why’s that?”

“It’s the mass thing again. At any given temperature, helium atoms in a gas zip around four times faster than oxygen molecules do. Anyway, the helium atoms that arrive up top won’t stay there.”

“Where else would they go?”

“Anywhere else, basically. Have you heard the phrase, ‘escape velocity‘?”

“It has something to do with rockets, doesn’t it?”

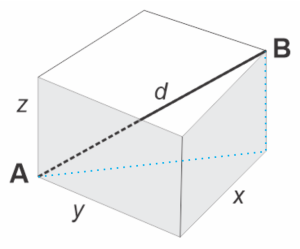

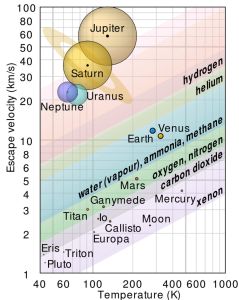

“Well, them, too. The general idea is that once you reach a certain threshold speed relative to a planet or something, you’re going too fast for its gravity to pull you back down. There’s a formula for calculating the speed. The fun thing is, the speed depends on the mass of what you’re escaping from and your distance from the object’s center, but it doesn’t depend on your own mass. It applies to everything from rockets to gas molecules.”

“And we were just talking about helium being zippy. Is it zippy enough to escape Earth?”

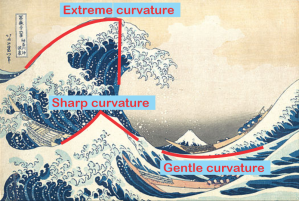

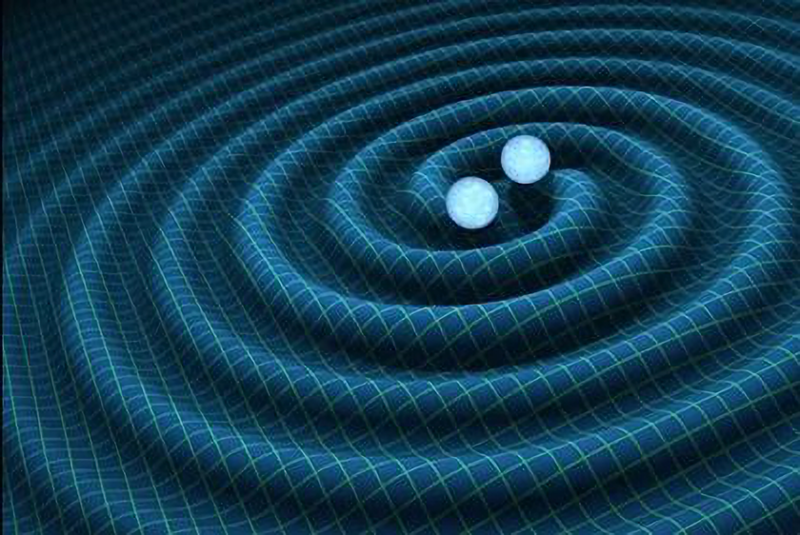

CCA-SA 3.0 Unported

“Good thinking! That’s exactly where I was going. The answer is, ‘Maybe.’ It depends on temperature. Warm molecules are zippy, cold molecules not so much. At the same temperature, light molecules are zippier than heavy ones. There’s a chart that shows thresholds for different molecules escaping from different planets. Earth could hold onto its helium atoms, but only if our atmosphere were more than a hundred degrees colder than it is. Warm as we are, bye‑bye helium.”

“How long would that take?”

“That’s a complicated question with lots of ‘It depends’ in the answer. Probably the most important has to do with water.”

“I didn’t say anything about water, just helium and oxygen.”

“I know, but much of Earth’s weather is driven by water vaporizing or condensing or just carrying heat from place to place. Water‑powered hurricanes and even big thunderstorms stir up the atmosphere enough to swoosh helium up to bye‑bye territory. On the other hand, suppose our helium‑Earth is dry. The atmosphere’s layers would be mostly stable, light atoms would be slow to rise. We’d have a very odd‑looking sky.”

“No clouds.”

“Pretty much. But it wouldn’t be blue, either.”

“Would it be pink? I like pink.”

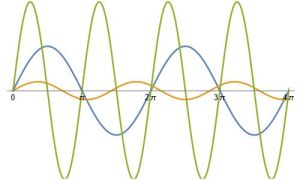

“Sorry, sweetie, it’d be dark dark blue, some lighter near the horizon. Light going past an atomic or molecular particle can scatter from its temporarily distorted electron cloud. Nitrogen and oxygen molecules distort more easily than helium atoms do. Earth skies are blue thanks to sunlight scattered by oxygen and nitrogen. Helium skies wouldn’t have much of that.”

~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks again to Xander, who asked a really good helium question.