“C’mon in, Sy.”

“Morning, Cathleen. You know my niece Teena.”

“Hi, Teena. What brings you here to my office?”

“I’m working on a school project about eclipses, Dr O’Meara, and I noticed something weird. Uncle Sy said you could explain it to me. You know how an eclipse isn’t in just one place, the Moon writes its shadow along a track?”

“Of course, dear, I do teach Astronomy.”

“Sorry, I was just giving context.” <Cathleen and I give each other a look.> “Anyhow, I found this picture of lots of eclipse tracks and see how they weave together almost like cloth?”

“Oh, it’s better than that, Teena. Look at the dates. Is there a pattern there, too?”

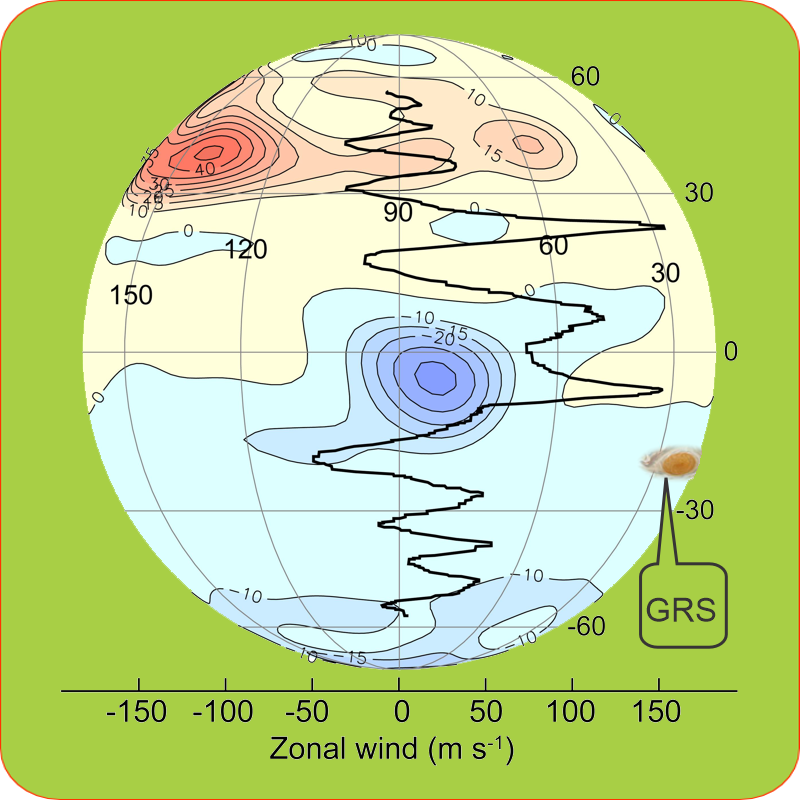

“Oooh, the Springtime ones go northeast and the Fall ones go southeast. Hey, I don’t see any in the Summer or Winter! Why is that?”

“It’s complicated, because it’s the result of several kinds of motion all going on at once. Have you ever played with a gyroscope?”

“Uh-huh, Uncle Sy gave me one for my birthday last year. He said that 10 years was old enough I could make it spin without hitting someone’s eye with the string. He was mostly right and I promise I really wasn’t aiming at Brian.”

<another look> “Well … okay. What’s a gyroscope’s special thing?”

“Once you start it spinning it tries to stay pointing in the same direction, except mine acts dizzy a little. Uncle Sy says the really good ones they put in satellites don’t get hardly get dizzy at all.”

“Good, you know gyroscope behavior. Planets spin, too, though a lot slower than your gyroscope. Do you know about planets?”

“Oh yes, when I was small and we looked at the eclipse my Mom and Uncle Sy explained about how we live on a planet that goes round the Sun and sometimes the Moon gets in the way and makes a shadow on us but when the Earth turns so we’re facing away from the Sun we’re in Earth’s shadow.”

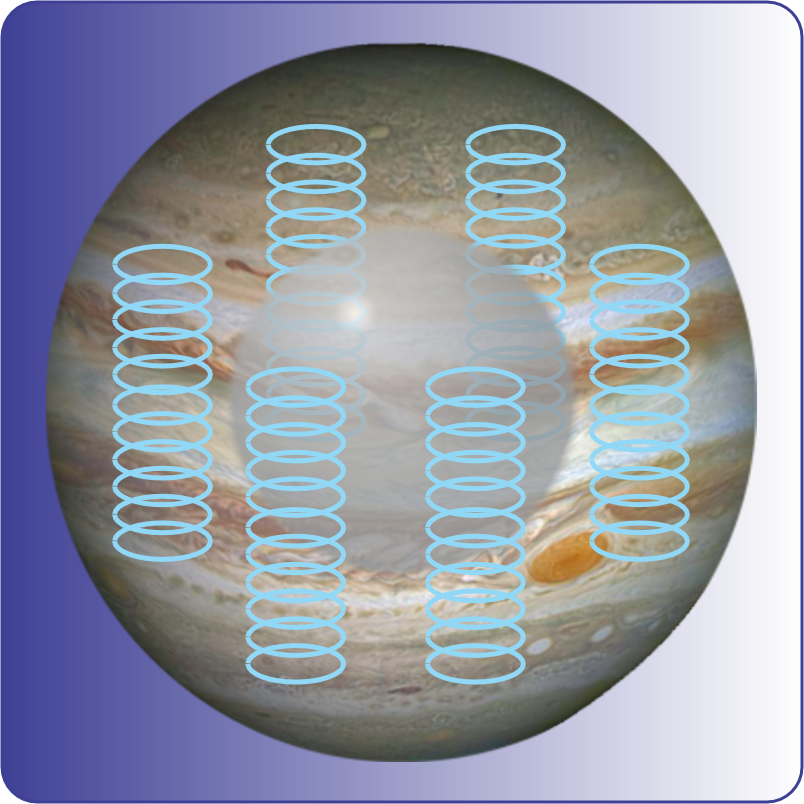

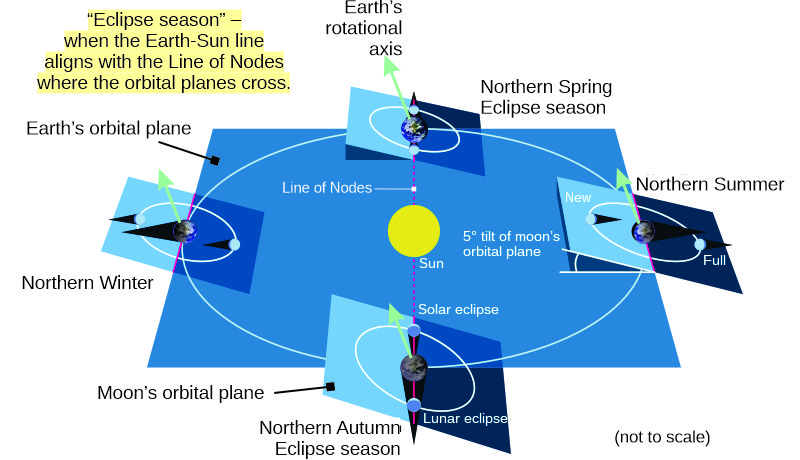

“Nice. Well, here’s a diagram about how eclipses happen. It shows four Earth‑images at special points in its orbit. Each Earth has Moon‑images at two special points in the Moon’s orbit. There’s also an arrow coming out of each Earth’s North Pole to show the axis that the Earth spins on. We’ve got three circular motions and each one acts like your gyroscope.”

“Does the Moon spin, too?”

“We talked about this a couple years ago, sweetie. The Moon always keeps one face towards the Earth so it spins once each month as it orbits around the Earth. Dr O’Meara’s just using a single circle to cover both, okay?”

“Okay. So there’s three gyroscopes, four really but one’s hiding. The picture says that all three point in different directions, right, and they stay that way?”

“Perfect.”

“Excuse me, but those angles don’t look right. The Earth axis is pointed too close or something.”

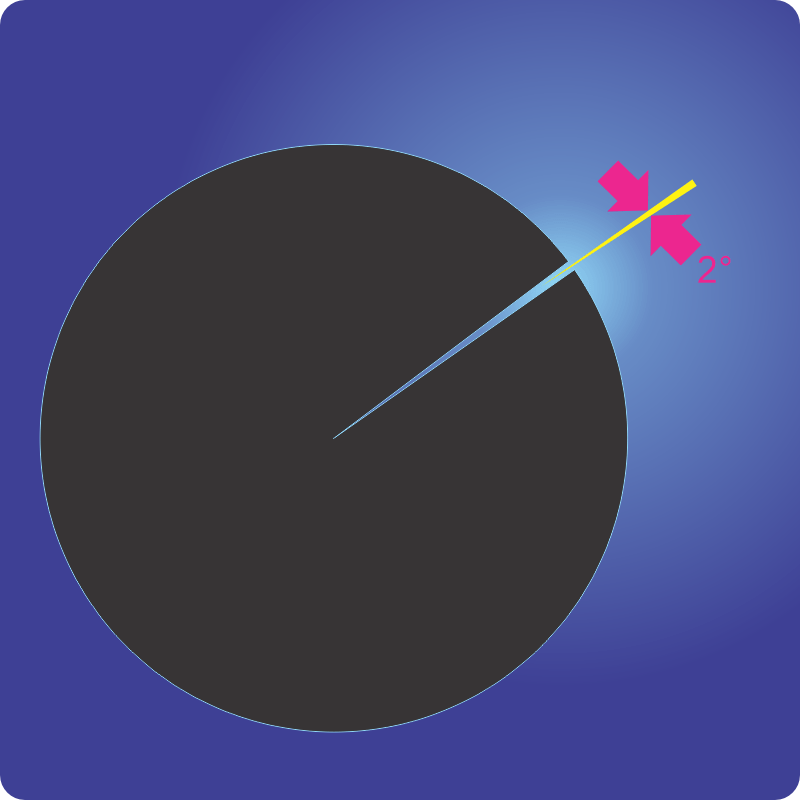

“Sharp, Sy. You’re partially correct. Actually, that axis is at a proper 23° angle from the perpendicular to Earth’s orbital plane. It’s the lunar orbital plane and its axis that are off. They’re supposed to be at a 5° angle to Earth’s plane but they’re drawn at 15° to highlight that important line where the two planes meet. The gyroscopes keep that line steady all year.”

“What’s so important about the line?”

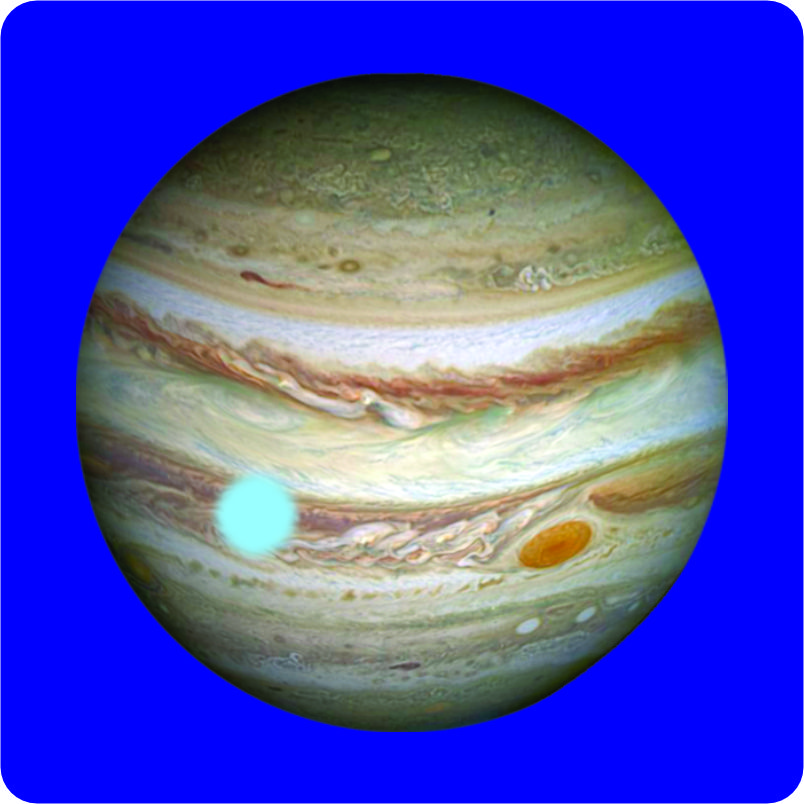

“If the Moon is too far above or below Earth’s plane, its shadow is too far above or below Earth to make an eclipse. Eclipses only happen when the line runs through the Sun AND when the Moon is close to the line. The line only runs through the Sun in the Spring and Fall, in this century anyway, so those are our eclipse seasons.”

“Why not every century?”

“A century ago, the eclipses came a few months earlier. The gyroscopes slowly drag the line around Earth’s solar orbit, shifting when the eclipse seasons arrive. If you want a New Year eclipse you’ll have to wait a long, long time.”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Naomi Pequette, Peak Nova Solutions, whose “Eclipses” presentation inspired this post.