I’m in the scone line at Cal’s Coffee when suddenly there’s a too‑familiar poke at my back, a bit right of the spine and just below the shoulder blade. I don’t look around. “Morning, Cathleen.”

“Morning, Sy. Your niece Teena certainly likes auroras, doesn’t she?”

“She likes everything. She’s the embodiment of ‘unquenchable enthusiasm.’ At that age she’s allowed.”

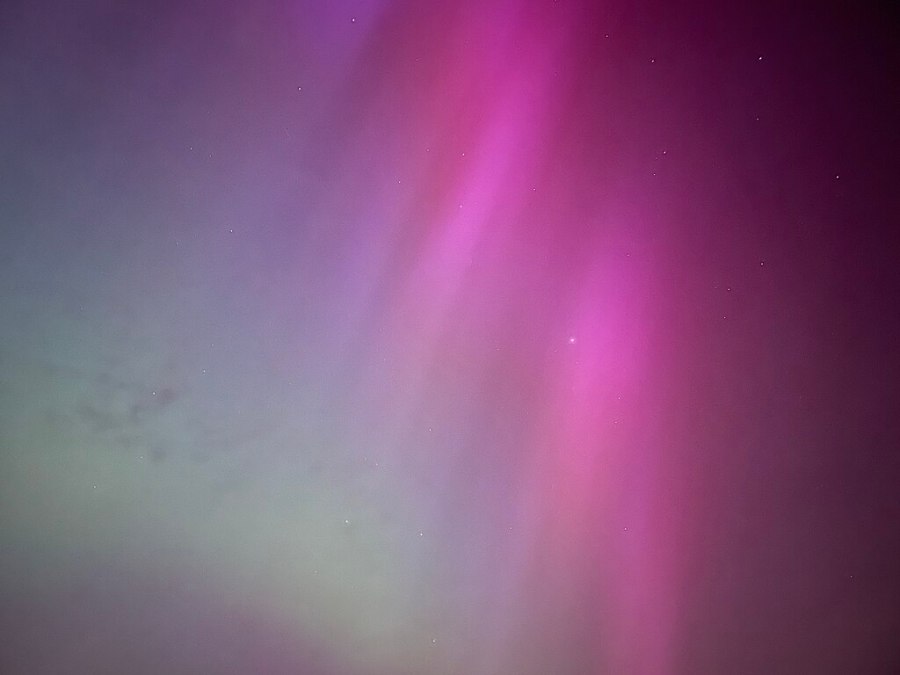

“It’s a gift at any age. Some of the kids in my classes, they just can’t see the wonders no matter how I try. I show them aurora photos and they say, ‘Oh yes, red and green in the sky‘ and go back to their phone screens. Of course there’s no way to get them outside late at night at a location with minimal light pollution.”

“I feel your pain.”

“Thanks. By the way, your aurora write-ups have been all about Earth’s end of the magnetic show. When you you going to do the rest of the story?”

“How do you mean?”

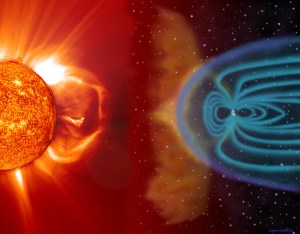

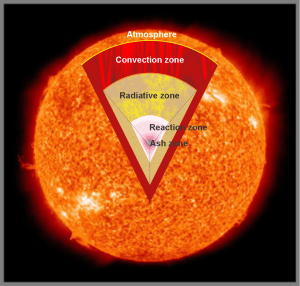

“Magnetism on the Sun, how a CME works, that sort of thing.”

“As a physicist I know a lot about magnetism, but you’re going to have to educate me on the astronomy.”

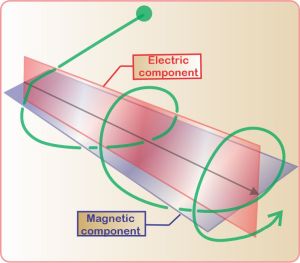

Electric (E) component is red

Magnetic (B) component is blue

(Image by Loo Kang Wee and Fu-Kwun Hwang from Wikimedia Commons)

Licensed under CC ASA3.0 Unported

“Deal. You go first.”

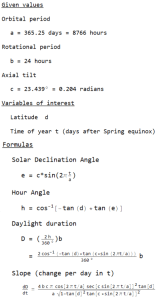

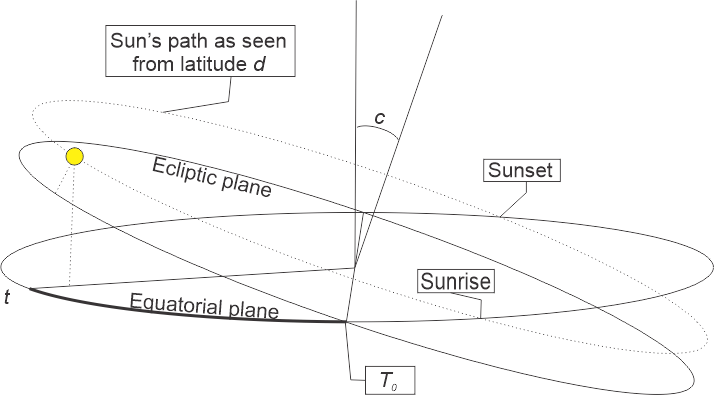

<displaying an animation on Old Reliable> “We’ll have to flip between microscopic and macroscopic a couple times. Here’s the ultimate micro — a single charged particle bouncing up and down somewhere far away has generated this Lorentz‑force wave traveling all alone in the Universe. The force has two components, electric and magnetic, that travel together. Neither component does a thing until the wave encounters another charged particle.”

“An electron, right?”

“Could be but doesn’t have to be. All the electric component cares about is how much charge the particle’s carrying. The magnetic component cares about that and also about its speed and direction. Say the Lorentz wave is traveling east. The magnetic component reaches out perpendicular, to the north and south. If the particle’s headed in exactly the same direction, there’s no interaction. Any other direction, though, the particle’s forced to swerve perpendicular to both the field and the original travel. Its path twists up- or downward.”

“But if the particle swerves, won’t it keep swerving?”

“Absolutely. The particle follows a helical path until the wave gives out or a stronger field comes along.”

“Wait. If a Lorentz wave redirects charge motion and moving charges generate Lorentz waves, then a swerved particle ought to mess up the original wave.”

“True. It’s complicated. You can simplify the problem by stepping back far enough that you don’t see individual particles any more and the whole assembly looks like a simple fluid. We’ve known for centuries how to do Physics with water and such. Newton invented hydrodynamics while battling the ghost of Descartes to prove that the Solar System’s motion was governed by gravity, not vortices in an interplanetary fluid. People had tried using Newton‑style hydrodynamics math to understand plasma phenomena but it didn’t work.”

<grinning> “I don’t imagine it would — all that twistiness would have thrown things for a loop.”

“Haha. Well, in the early 1940s Swedish physicist Hannes Alfven started developing ideas and techniques, extending hydrodynamics to cover systems containing charged particles. Their micro‑level electromagnetic interactions have macro‑level effects.”

“Like what?”

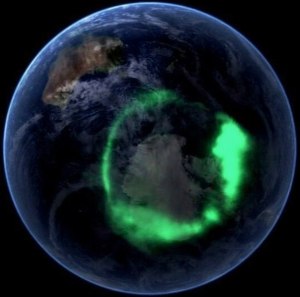

“Those aurora curtains up there. Alfven showed that in a magnetic field plasmas can self‑organize into what he called ‘double layers’, pairs of wide, thin sheets with positive particles on one side against negative particles in the other. Neither sheet is stable on its own but the paired‑up structure can persist. Better yet, plasma magnetic fields can support coherent waves like the ones making that curtain ripple.”

“Any plasma?”

“Sure.”

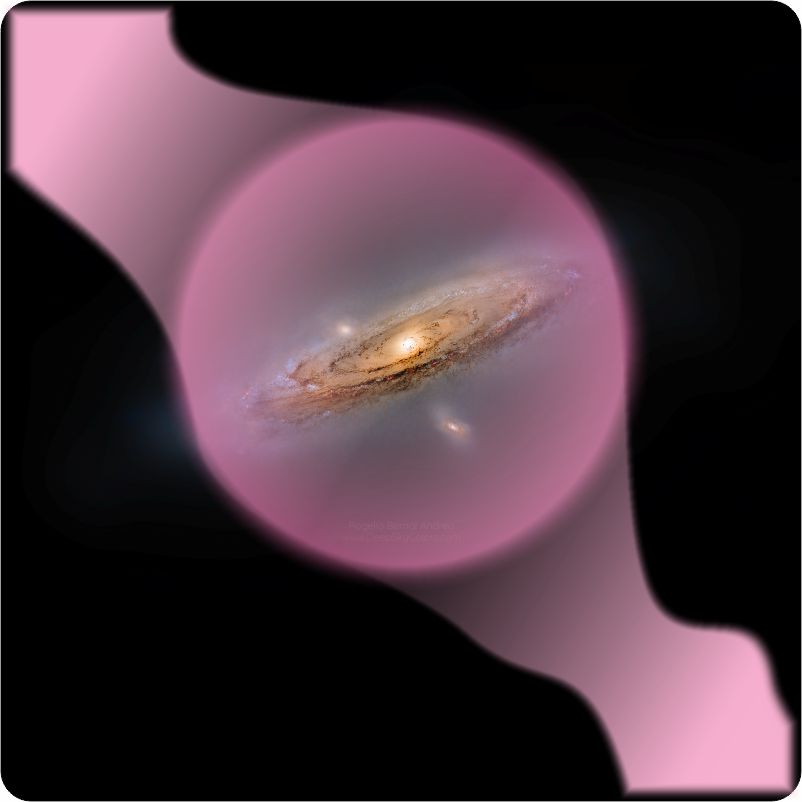

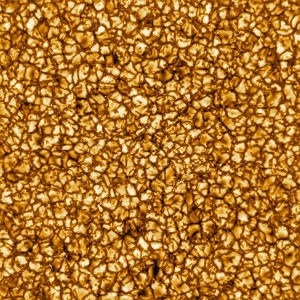

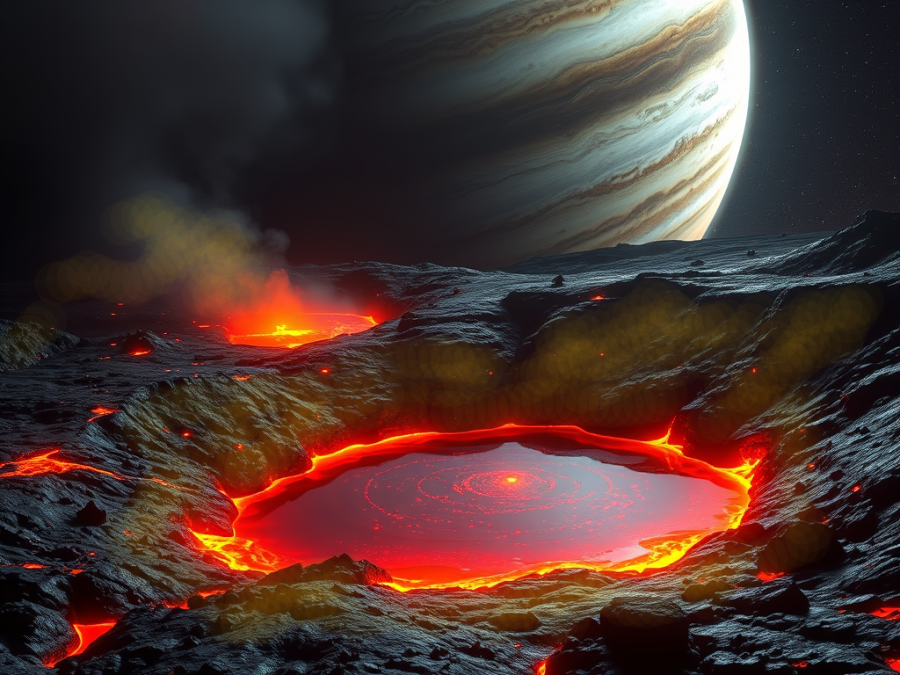

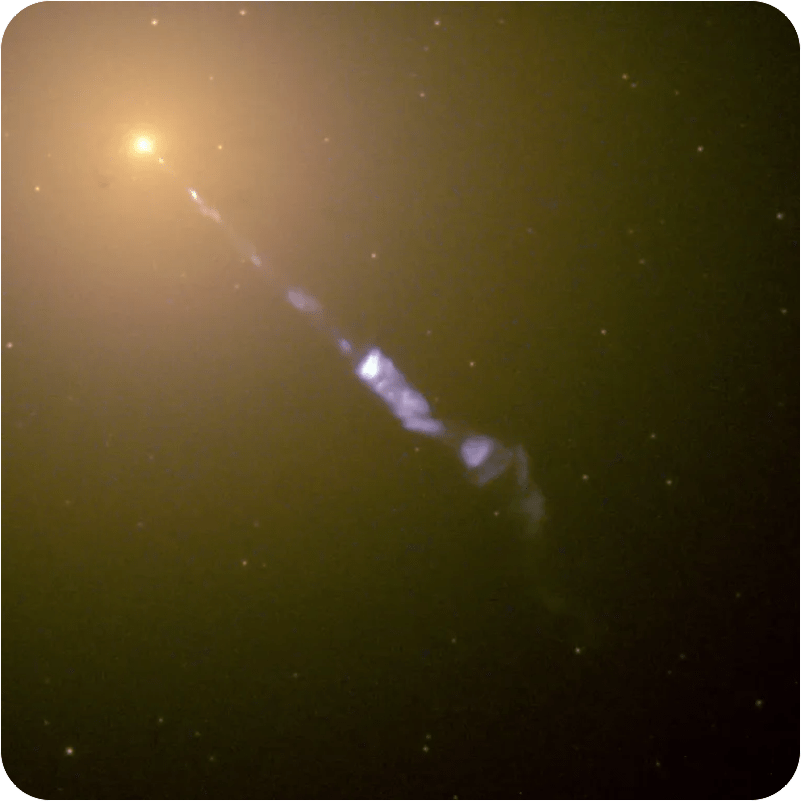

“Most of the astronomical objects I show my students are associated with plasmas — the stars themselves, of course, but also the planetary nebulae that survive nova explosions, the interstellar medium in galactic star‑forming regions, the Solar wind, CMEs…”

“Alfven said we can’t understand the Universe unless we understand magnetic fields and electric currents.”

~ Rich Olcott