It’s either late Winter or early Spring, trying to make up its mind. Either way, today’s lakeside walk is calm until I get to the parking lot and there he is, all bundled up and glaring at a huge pile of snow. “Morning, Mr Feder. You look even more out of sorts than usual. Why so irate?”

“The city’s dump truck buried my car in that stuff.”

“Your car’s under that? But there’s a sign saying not to park in that spot when there’s a snow event.”

“Yeah, yeah. Back on Fort Lee we figure the city just puts up signs like that to remind us we pay taxes. I’ll park where I want to. Freedom!”

“I’m beginning to understand you better, Mr Feder. Got a spare shovel? I can help you dig out.”

“My car shovel’s in the car, of course. I got another one at home for the sidewalk.”

I notice something, move over for a better view. “Step over here and look close just above the top of the pile where the sunlight’s hitting it.”

“Smoke! My car’s burning up under there!”

“No, no, something much more interesting. You’re looking at something that I’ve seen only a couple of times so you’re a lucky man. That’s steam, or it would be steam at a slightly higher temperature. What you’re looking at is distilled snow. See the sparkles from ice crystals in that cloud? Beautiful. Takes a very special set of circumstances to make that happen.”

“I’d rather be lucky in the casino. What’s so special?”

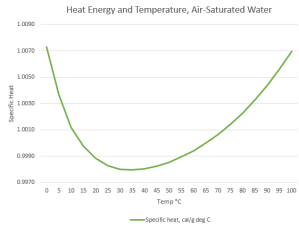

“The air has to be still, absolutely no breeze to sweep floating water molecules away from the pile. Temperature below freezing but not too much. Humidity at the saturation point for that temperature. Bright sun shining on snow that’s a bit dirty.”

“Dirty’s good?”

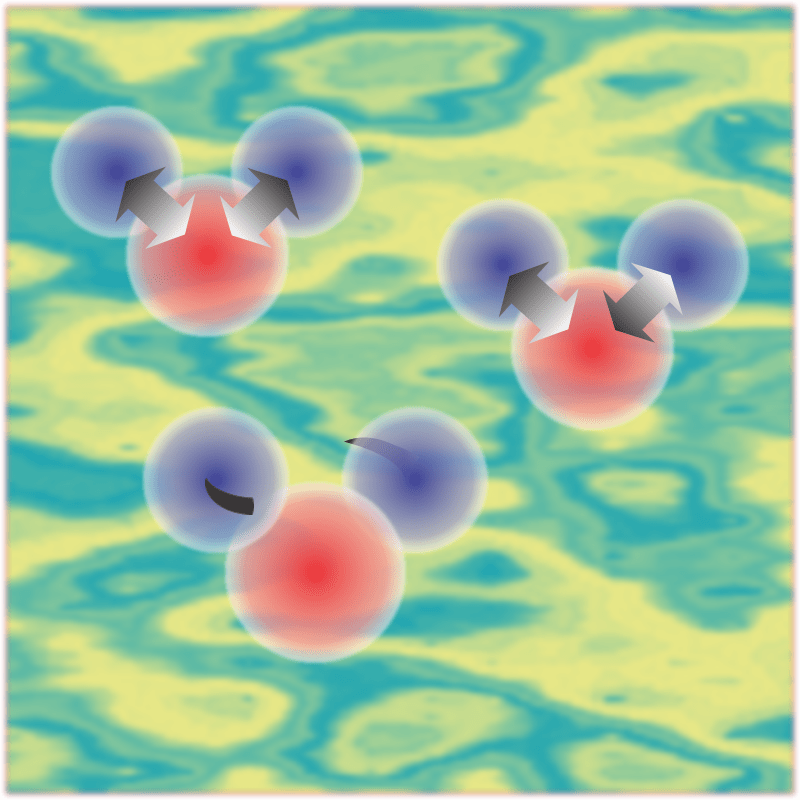

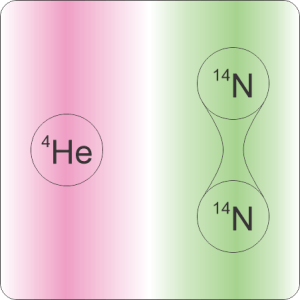

“In this case. Here’s the sequence. Snow is water molecules locked into a crystalline structure, right? Most of them are bonded to neighbors top, bottom and every direction. The molecules on the surface don’t have as many neighbors, right, so they’re not bonded as tightly. So along comes sunlight, not only visible light but also infrared radiation—”

“Infrared’s light, too?”

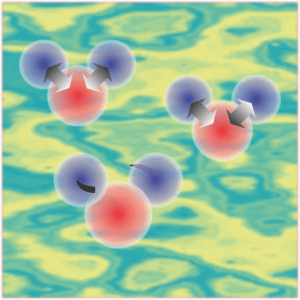

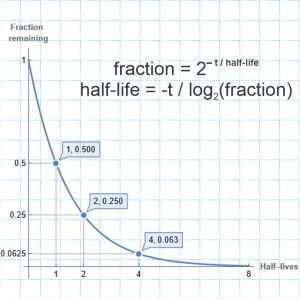

“Mm-hm, just colors we can’t see. Turns out because of quantum, infrared light photons are even more effective than visible light photons when it comes to breaking water molecules away from their neighbors. So a top molecule, I’ll call it Topper, escapes its snow crystal to float around in the air. Going from solid directly to free-floating gas molecules, we call that sublimation. Going the other way is deposition. Humidity’s at saturation, right, so pretty soon Topper runs into another water molecule and they bond together.”

<sarcasm, laid on heavily> “And they make a cute little snow crystal.”

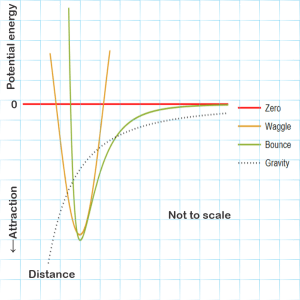

“Not so fast. With only two molecules in the structure, you can’t call it either solid or liquid but it does grow by adding on more molecules. Thing is, every molecule they encounter gives up some heat energy as it ties down. If the weather’s colder than it is here, that’s not enough to overcome the surrounding chill. The blob winds up solid, falls back down onto the pile. If it’s just a tad warmer you get a liquid blob that warms the sphere of air around it just enough to float gently upwards—”

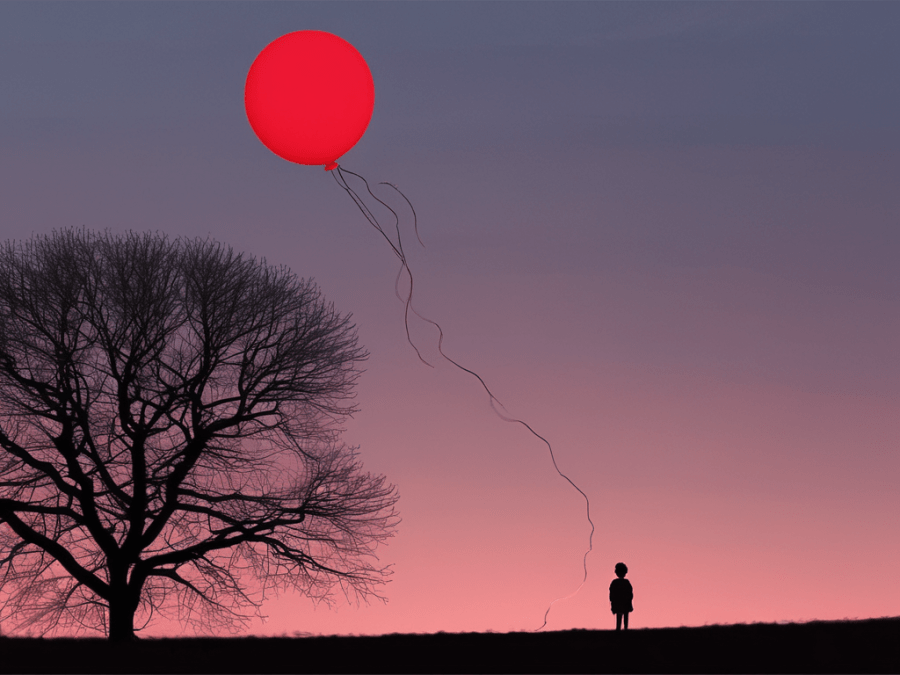

“Like a balloon, I got the picture.”

“Floats up briefly. It doesn’t get up far before the surrounding chill draws out that heat and wins again. Not so brief when there’s a little dirt in there.”

“The dirt floats?”

“Of course not. The dirt’s down in the snow pile, but it’s dark and absorbs more sunlight energy than snow crystals do. What the dirt does is, it tilts the playing field. Heat coming from the dirt particles increases the molecular break‑free rate and there’s more blobs. It also warms the air around the blobs and floats them high enough to form this sparkling cloud we can see and enjoy.”

“You can enjoy it. I’m seeing my car all covered over and that’s not improving my mood.”

“Better head home for that shovel, Mr Feder. The snow dumper’s coming back with another load.”

~ Rich Olcott