“How the heck do they know that?”

“Know what, Vinnie?”

“That the galaxy they saw with that gravitational lens is 13 billion years old? I mean, does it come with a birth certificate, Cathleen?”

“Mm, it does, sort of — hydrogen atoms. Really old hydrogen atoms.”

“Waitaminit. Hydrogen’s hydrogen — one proton, one electron per atom. They’re all the same, right? How do you know one’s older than another one?”

“Because they look different.”

“How could they look different when they’re all the same?”

“Let me guess, Cathleen. These old hydrogens, are they far far away?”

“On the button, Sy.”

“What where they’re at got to do with it?”

“It’s all about spectroscopy and the Hubble constant, Vinnie. What do you know about Edwin Hubble?”

“Like in Hubble Space Telescope? Not much.”

“Those old atoms were Hubble’s second big discovery.”

“Your gonna start with the other one, right?”

“Sorry, classroom habit. His first big discovery was that there’s more to the Universe than just the Milky Way Galaxy. That directly contradicted Astronomy’s Big Names. They all believed that the cloudy bits they saw in the sky were nebulae within our galaxy. Hubble’s edge was that he had access to Wilson Observatory’s 100-inch telescope that dwarfed the smaller instruments that everyone else was using. Bigger scope, more light-gathering power, better resolution.”

“Hubble won.”

“Yeah, but how he won was the key to his other big discovery. The crucial question was, how far away are those ‘nebulae’? He needed a link between distance and something he could measure directly. Stellar brightness was the obvious choice. Not the brightness we see on Earth but the brightness we’d see if we were some standard distance away from it. Fortunately, a dozen years earlier Henrietta Swan Leavitt found that link. Some stars periodically swing bright, then dim, then bright again. She showed that for one subgroup of those stars, there’s a simple relationship between the star’s intrinsic brightness and its peak-to-peak time.”

“So Hubble found stars like that in those nebulas or galaxies or whatever?”

“Exactly. With his best-of-breed telescope he could pick out individual variable stars in close-by galaxies. Their fluctuation gave him intrinsic brightness. The brightness he measured from Earth was a lot less. The brightness ratios gave him distances. They were a lot bigger than everyone thought.”

“Ah, so now he’s got a handle on distance. Scientists love to plot everything against everything, just to see, so I’ll bet he plotted something against distance and hit jackpot.”

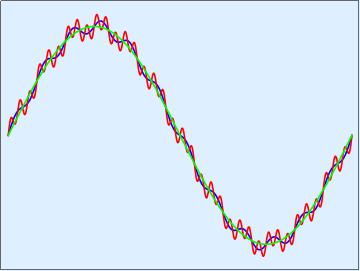

“Well, he was a bit less random than that, Sy. There were some theoretical reasons to think that the Universe might be expanding. The question was, how fast? For that he tapped another astronomer’s results. Vesto Slipher at Lowell Observatory was looking at the colors of light emitted by different galaxies. None had light exactly like our Milky Way’s. A few were a bit bluer, but most were distinctly red-shifted.”

“Like the Doppler effect in radar? Things coming toward you blue-shift the radar beam, things going away red-shift it?”

“Similar to that, Vinnie, but it’s emitted light, not a reflected beam. To a good approximation, though, you can say that the red shift is proportional to the emitting object’s speed towards or away from us. Hubble plotted his distance number for each galaxy he’d worked on, against Slipher’s red-shift speed number for the same galaxy. It wasn’t the prettiest graph you’ve ever seen, but there was a pretty good correlation. Hubble drew the best straight line he could through the points. What’s important is that the line sloped upward.”

“Lemme think … If everything just sits there, there’d be no red-shift and no graph, right? If everything is moving away from us at a steady speed, then the line would be flat — zero slope. But he saw an upward slope, so the farther something is the faster it’s going further from us?”

“Bravo, Vinnie. That’s the expansion of the Universe you’ve heard about. Locally there are a few things coming toward us — that’s those blue-shifted galaxies, for instance — but the general trend is away.”

“So that’s why you say those far-away hydrogens look different. By the time we see their light it’s been red-shifted.”

“93% redder.”

~~ Rich Olcott

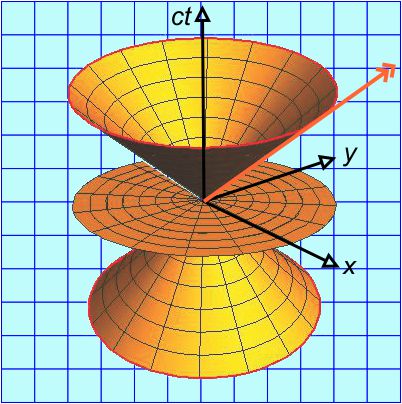

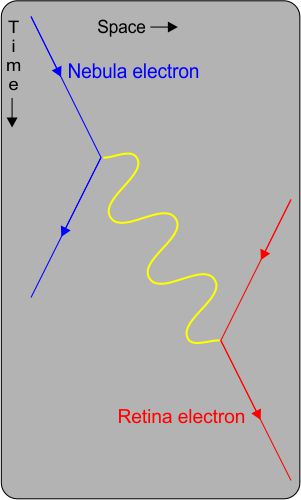

Last week’s Minkowski diagram was two-dimensional. It showed time running along the vertical axis and Pythagorean distance d=√(x²+y²+z²) along the horizontal one. That was OK in the days before computer graphics, but it loaded many different events onto the same point on the chart. For instance, (0,1,0,0), (0,-1,0,0), (0,0,1,0) and (0,0,0,1) (and more) are all at d=1.

Last week’s Minkowski diagram was two-dimensional. It showed time running along the vertical axis and Pythagorean distance d=√(x²+y²+z²) along the horizontal one. That was OK in the days before computer graphics, but it loaded many different events onto the same point on the chart. For instance, (0,1,0,0), (0,-1,0,0), (0,0,1,0) and (0,0,0,1) (and more) are all at d=1.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

Nonetheless, mathematicians and cryptographers have forged ahead, calculating π to more than a trillion digits. Here for your enjoyment are the 99 digits that come after digit million….

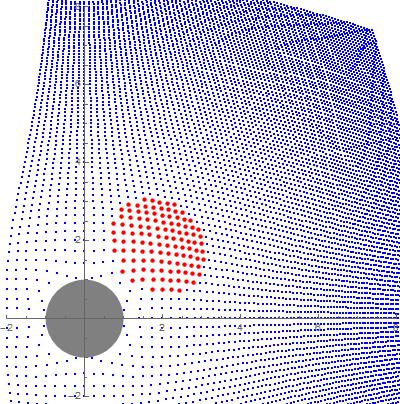

Nonetheless, mathematicians and cryptographers have forged ahead, calculating π to more than a trillion digits. Here for your enjoyment are the 99 digits that come after digit million…. Back to π. The Greeks knew that the circumference of a circle (c) divided by its diameter (d) is π. Furthermore they knew that a circle’s area divided by the square of its radius (r) is also π. Euclid was too smart to try calculating the area of the visible sky in his astronomical work. He had two reasons — he didn’t know the radius of the horizon, and he didn’t know the height of the sky. Later geometers worked out the area of such a spherical cap. I was pleased to learn that π is the ratio of the cap’s area to the square of its chord, s2=r2+h2.

Back to π. The Greeks knew that the circumference of a circle (c) divided by its diameter (d) is π. Furthermore they knew that a circle’s area divided by the square of its radius (r) is also π. Euclid was too smart to try calculating the area of the visible sky in his astronomical work. He had two reasons — he didn’t know the radius of the horizon, and he didn’t know the height of the sky. Later geometers worked out the area of such a spherical cap. I was pleased to learn that π is the ratio of the cap’s area to the square of its chord, s2=r2+h2. Astrophysicists and cosmologists look at much bigger figures, ones so large that curvature has to be figured in. There are three possibilities

Astrophysicists and cosmologists look at much bigger figures, ones so large that curvature has to be figured in. There are three possibilities

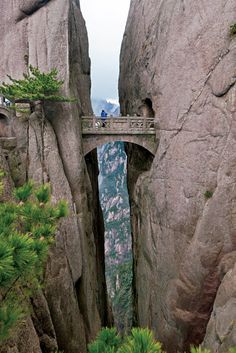

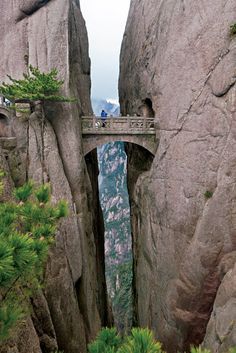

See that little guy on the bridge, suspended halfway between all the way down and all the way up? That’s us on the cosmic size scale.

See that little guy on the bridge, suspended halfway between all the way down and all the way up? That’s us on the cosmic size scale. So that’s the size range of the Universe, from 1.6×10-35 up to 2.6×1026 meters. What’s a reasonable way to fix a half-way mark between them?

So that’s the size range of the Universe, from 1.6×10-35 up to 2.6×1026 meters. What’s a reasonable way to fix a half-way mark between them?