“Okay, Sy, what’s your third solution?”

“Solution to what, Susan?”

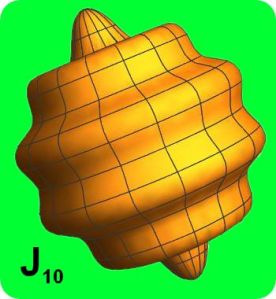

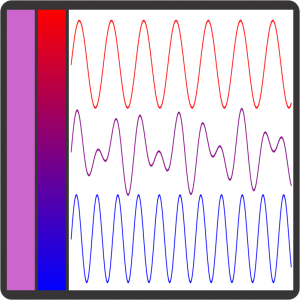

“These harmonic thingies. They’re about angles so it makes sense to chart them in polar or spherical coordinates, but when they take on negative values the radius goes the wrong way. You said one solution was to chart the negatives in a different color. That’s confusing, though. Another solution is to square all the values to get everything into positive territory. That’s okay for chemists like me because the peaks and nodes we care about stay in the same places. What’s the third option?”

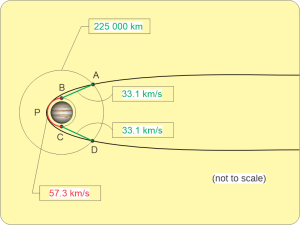

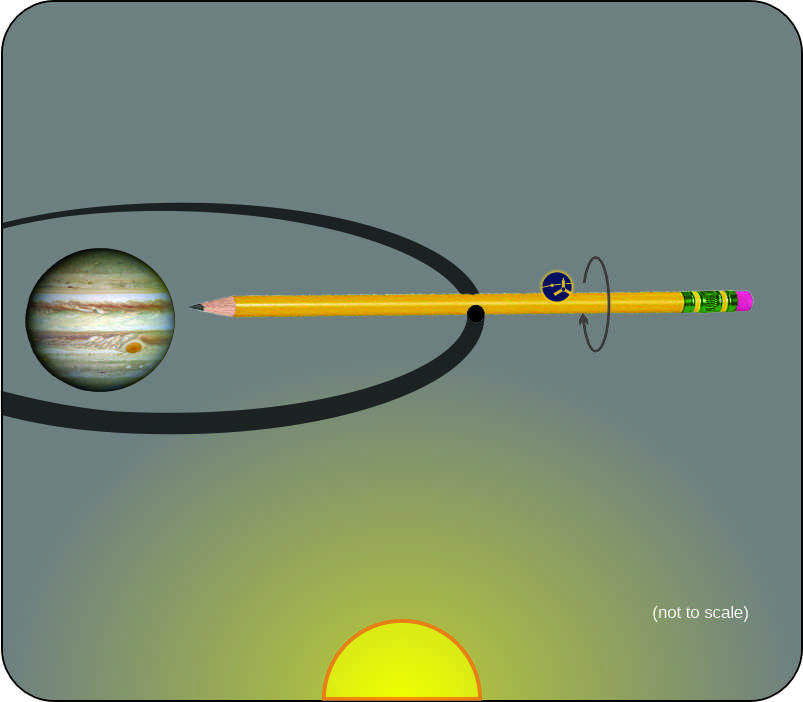

“One that gets to why these ‘harmonic thingies’ are interesting at all. When Juno‘s orbiting Jupiter, does it feel each of Kaspi’s Jn shapes individually?”

“No, of course not, she just reacts to how they all add togethherrr … Oh! So you’re saying we can handle negative values from one harmonic by adding it to another one that’s more positive and plotting the combination.”

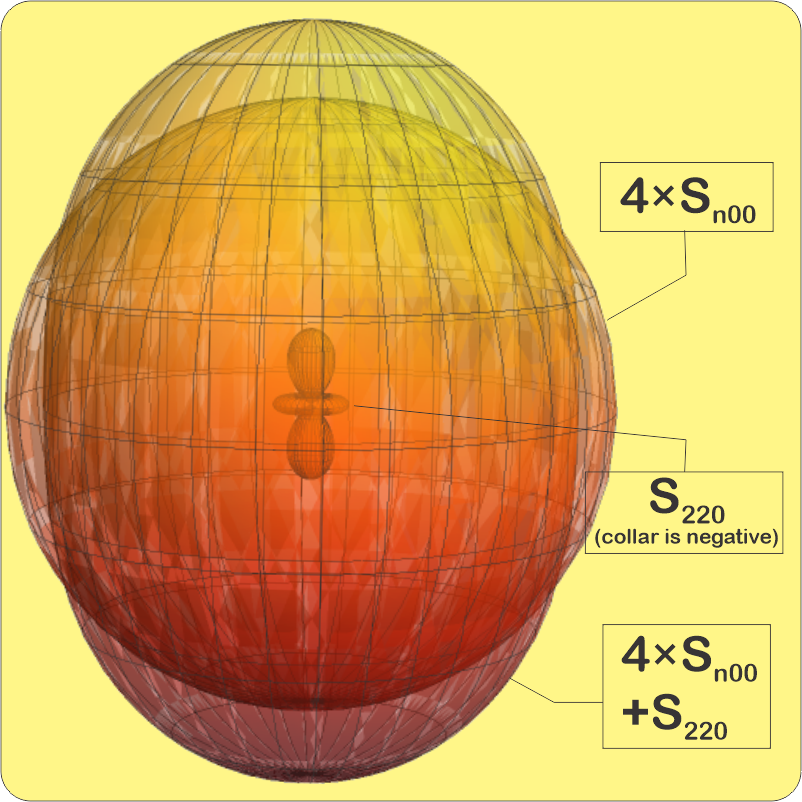

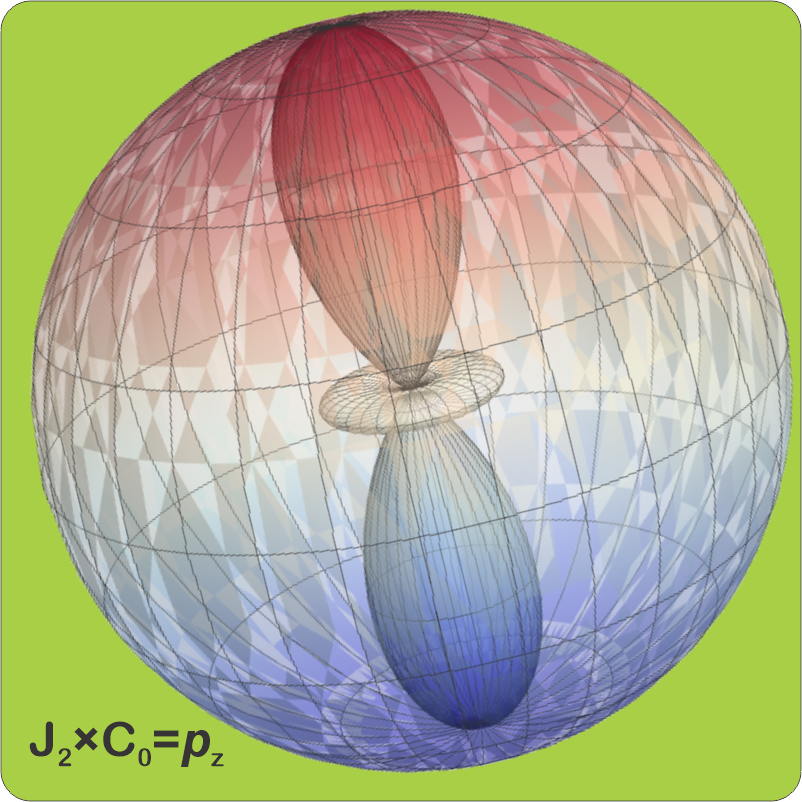

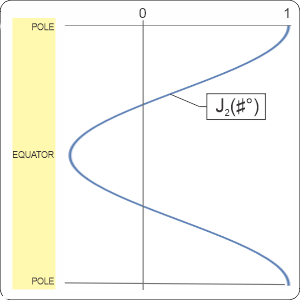

<pointing to paper napkin> “Bingo! Remember this linear plot of J2 where I colored its negative section pink?” <pointing to display on Old Reliable> “When you multiply J2 by C0 you get S220. I added that to four helpings of Sn00 to get this combination.”

“Ah, that negative region in S220‘s middle shaves back the equator on Sn00‘s sphere while the positive part adds bumps top and bottom.” <Susan gives me the side‑eye> “Why’d you pick that 4‑to‑1 ratio, and what’s with those n subscripts instead of numbers?”

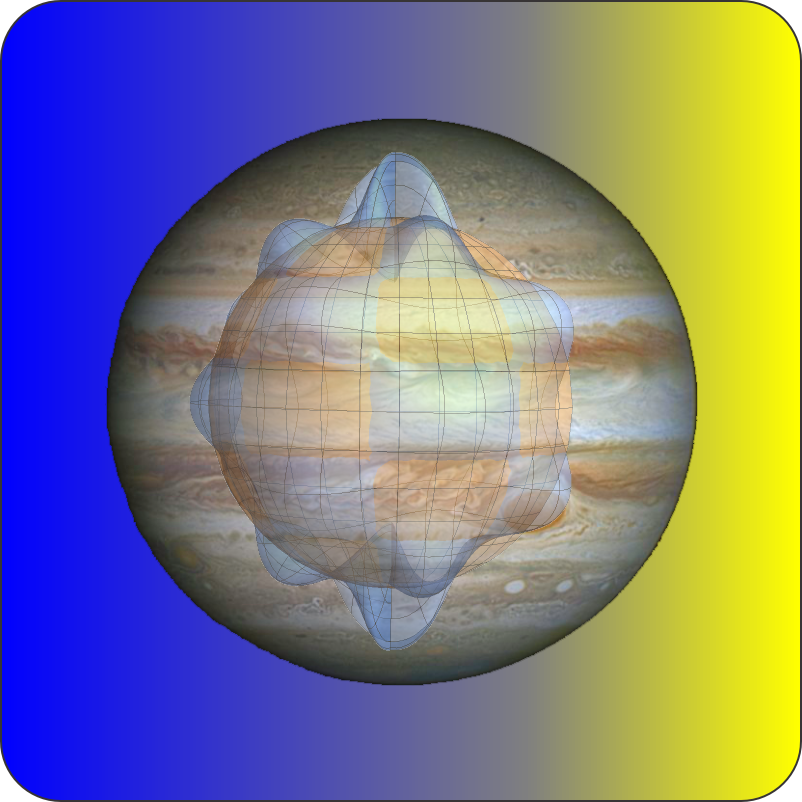

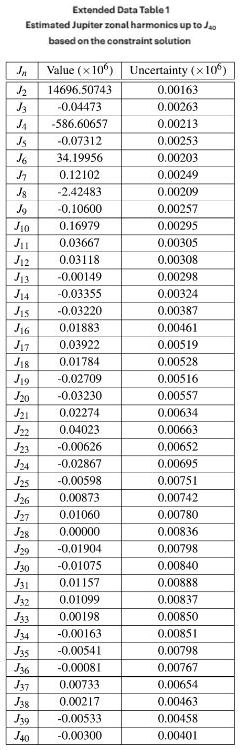

“Getting a little ahead of myself. For the moment let’s concentrate on Juno‘s experience with Jupiter’s gravity. One reason I chose that ratio was that it’s pretty easy to see in the picture. In real cases the physical system determines the ratios. Kaspi’s team derived their ratios experimentally. They used math to fit a model to Juno‘s very slightly wobbly orbit. Their model of Jupiter’s gravity field started from the spherical J0 shape. They tweaked that by adding different ratios of J2 through J40, adjusting the ratios until the model’s total gravity field predicted an orbit that matched the real‑world one. J2‘s share was about 15 parts per thousand but most of the rest contributed less than a part per million. Jupiter probably uses multiple mass blobs to make the J2 shape. The point is, the planet’s really a mess but we can analyze the mess in terms of the harmonics.”

“So that’s how you drew what Cal called your wiggle-waggles — you followed Kaski’s Jn recipe and then added some constant to push the polar plot out far enough that the negatives didn’t poke out the wrong side. That constant — what value did you use and why that one?”

“That’s exactly what I did do, Cathleen. Frankly, I don’t even remember what constant I added, just something that was big enough to make the negatives behave nicely, not so large that the peaks vanished by comparison. Calibrating accurately to Jupiter’s J0 would shrink the peaks down to parts‑per‑thousand invisibility. After all, I was more concerned with peak position than peak size.”

“Now we’re back to your 4‑to‑1 ratio. Was that arbitrary, too?”

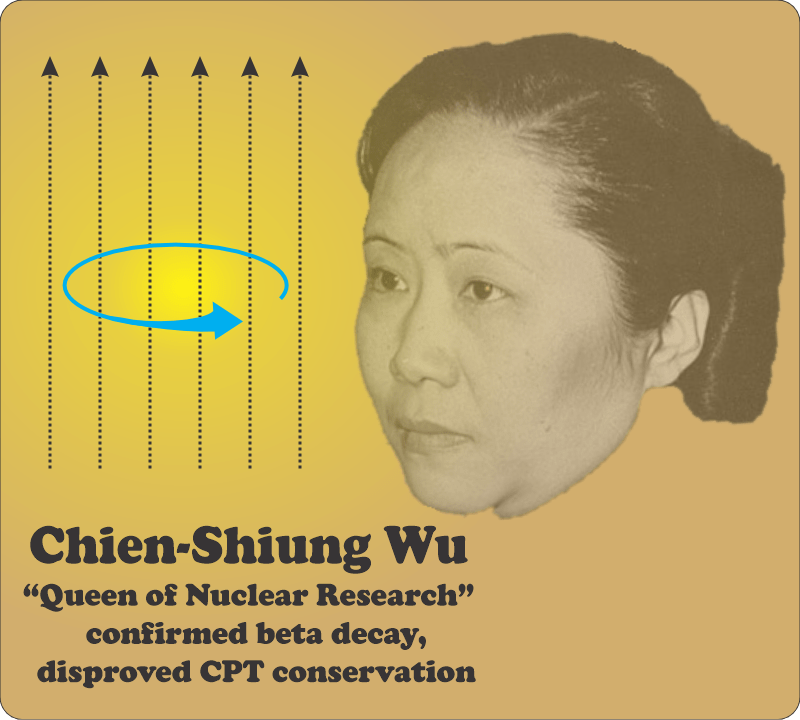

“No, it wasn’t, Susan. Would it have been closer to Chemistry if I’d labeled that figure as 1s22s22p1?”

“Two electrons in the 1s‑shell, two in the 2s‑shell plus one 2p electron … that’s a boron atom? But you’re showing only one radial shell, not two separate ones.”

“True, but that’s to make another point. There isn’t an electron in the 1s shell, or even a pair of them nicely staying on opposite sides. The atom’s charge, all five electrons‑worth of it, is smeared out as a wave pattern across the entire structure. The Sn00 pattern captures everything that’s spherical. The S220 pattern gets what’s left.”

“But what about the radial nodes? Isn’t that the difference between 1s and 2s, that 2s has a node?”

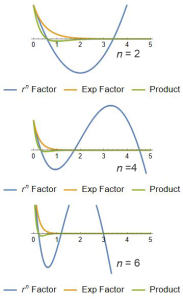

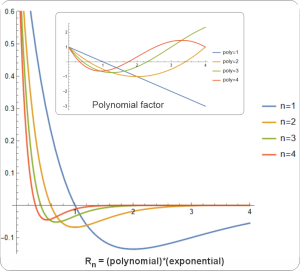

“Oh there are nodes, alright, but they don’t have much effect. Each radial harmonic is the product of two factors — a polynomial and an exponential. The exponential part squeezes the polynomial so hard that adjacent peaks and valleys are barely bumps and dents.”

“So Jupiter and atoms use the same math, huh?”

“So does the Sun.”

~~ Rich Olcott