Cal has my coffee mug filled as soon as I step into his shop. “Get to the back room quick, Sy. Cathleen’s got another Crazy Theories seminar going back there.”

So I do. First thing I hear is Amanda finishing her turn at the mic. “And that’s why humans evolved male pattern baldness.”

A furor of “Amanda! Amanda! Amanda!” then Cathleen regains control. “Thank you, Amanda. Next up — Newt Barnes. What’s your Crazy Theory, Newt?”

“Crazy idea, not a theory, but I like it. Everybody’s heard of black holes, right?”

<general nodding>

“And we’ve all heard that nothing can leave a black hole, not even light.”

<more nodding>

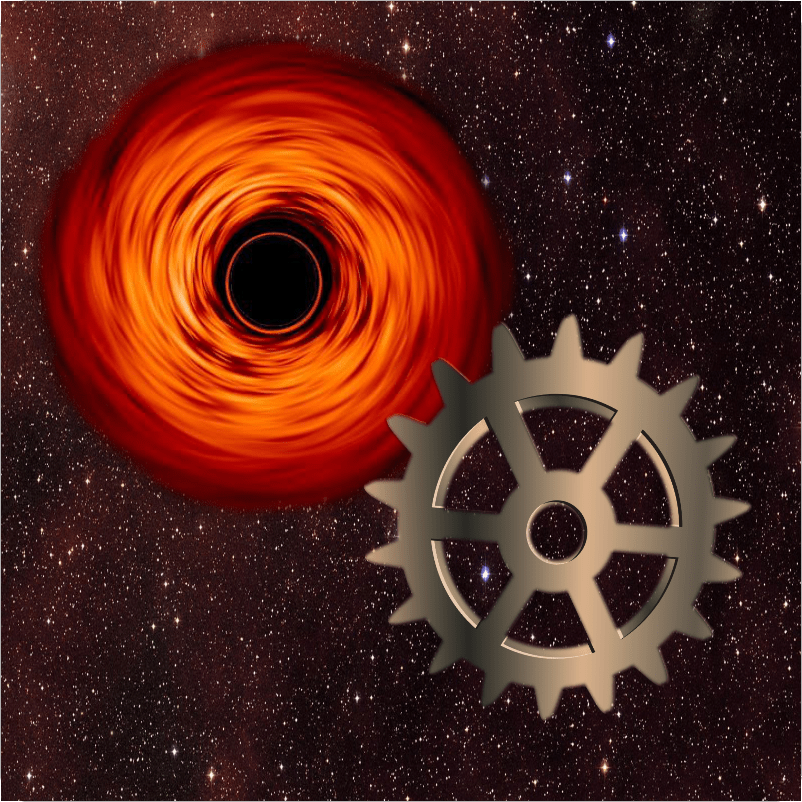

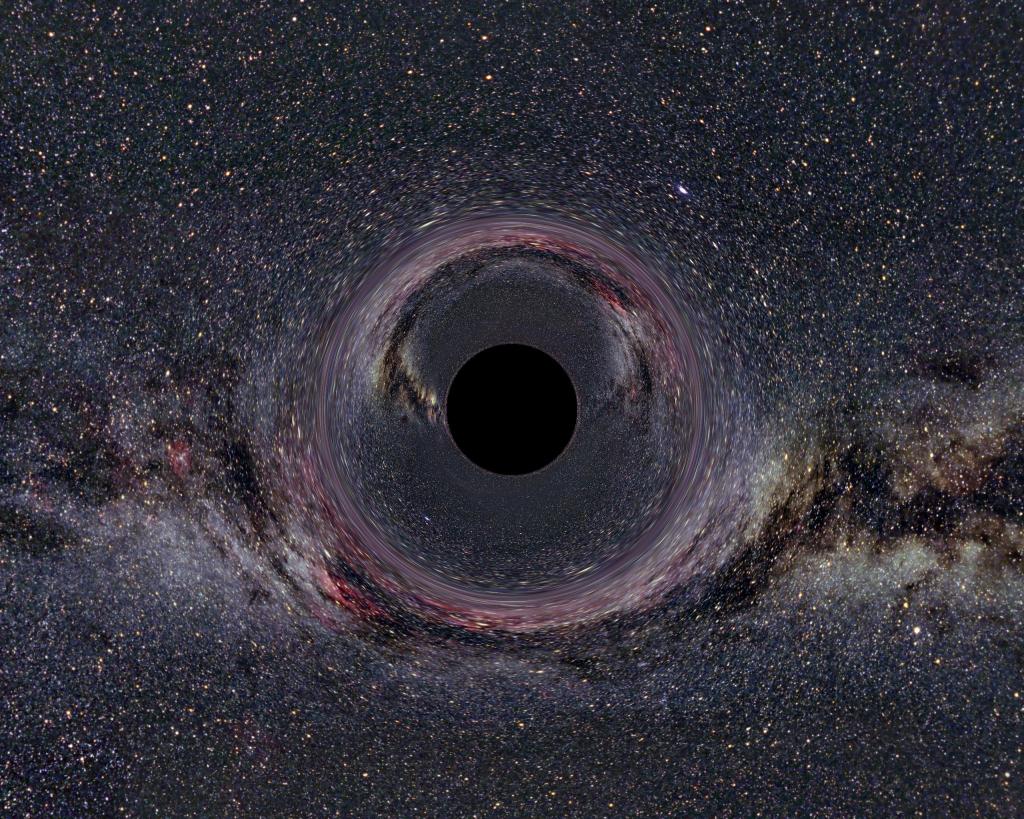

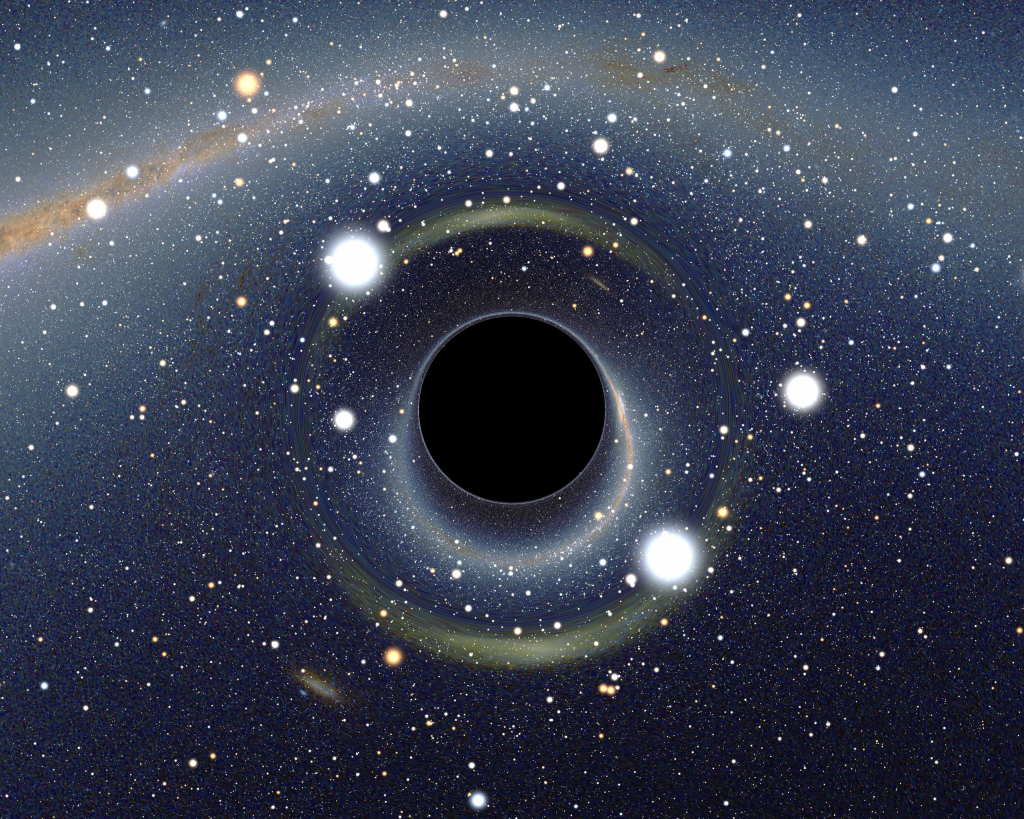

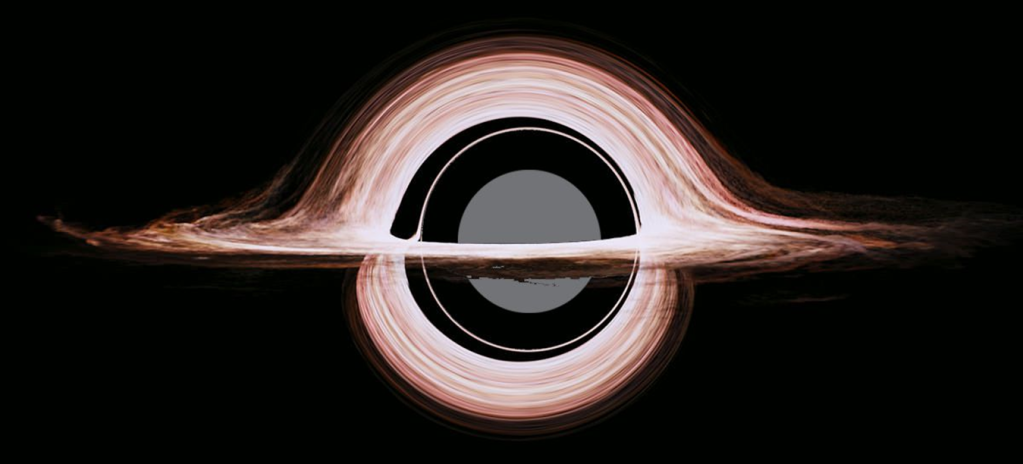

“Well in fact that’s mostly not true. There’s so much confusion about black holes. We’ve known about a black hole’s event horizon and its internal mass since the 1920s. It took years for us to realize that the central mass could wrap a shiny accretion disk around itself, and an ergosphere, and maybe spit out jets. So, close outside the Event Horizon there’s a lot of light‑emitting structure, right?”

<A bit less nodding, but still.>

“Right. So I’ll skip in past a few controversial layers and get down to the famously black event horizon. Why’s it black?”

Voice from the back of the room — “Because photons can’t get out because escape velocity’s faster than lightspeed.”

“That’s the answer I expected, but it’s also one of the confusing parts. You’re right, the horizon marks the level where outward‑bound massy particles can’t escape. The escape velocity equation depends on trading off kinetic and gravitational potential energy. Any particle with mass would have to convert an impossible amount of kinetic energy into gravitational potential energy to get through the barrier. But zero‑mass particles, photons and such, are pure kinetic energy. They aren’t bound by a gravitational potential so escape velocity trade‑offs simply don’t apply. There’s a deeper reason photons also can’t get out.”

VBOR — “So what’s trapping them?”

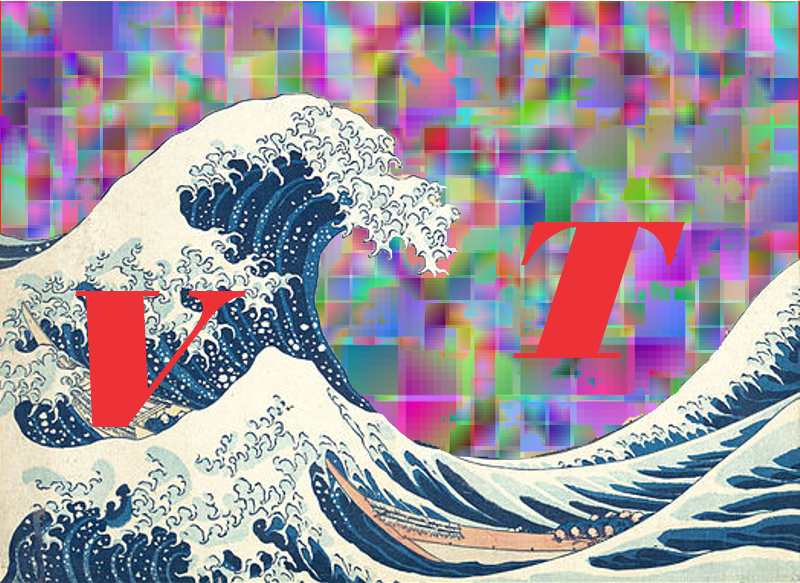

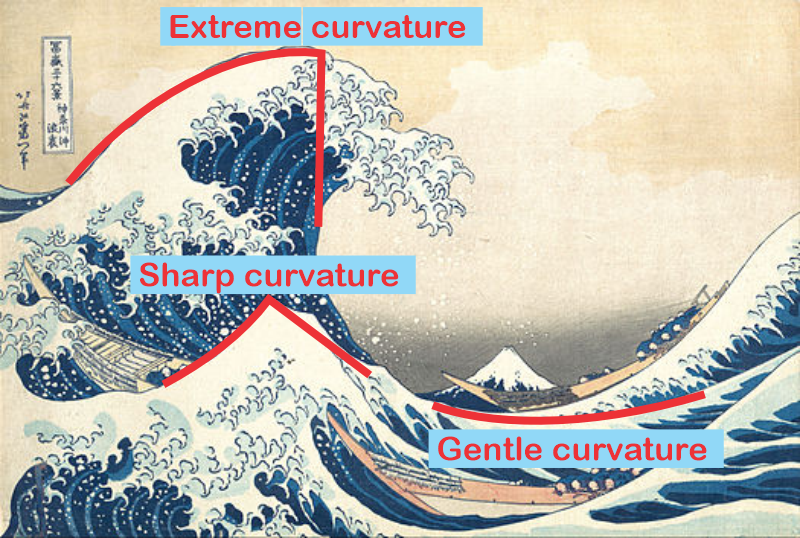

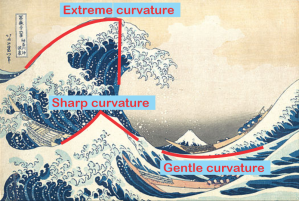

“Time. It traps photons and any kind of information. The other thing about the Event Horizon is, it’s the level where spacetime is so bent around that the time‑coordinate is just on the verge of pointing inward. Once you’re inside that boundary the cause‑and‑effect arrow of time is against you. Whatever direction you point your flashlight, its beam will emerge in your future and that’s away from the horizon. Trying to send a signal outside would be like sending it into your past, which you can’t do. Nothing gets away from a black hole except…”

“Except?”

“Roger Penrose found a loophole and I may have found another one. There’s something that Wheeler called the No-Hair Theorem. It says that the Event Horizon hides everything inside it except for its mass, electric charge and angular momentum.”

“How do those get out?”

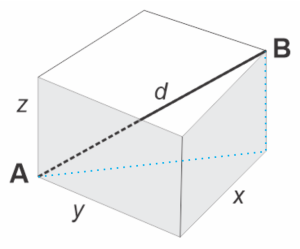

“They don’t get out so much as serve as backdrop for all the drama in the rest of the structure. If you know the mass, for instance, you can calculate its temperature and the Horizon’s diameter and a collection of other properties.”

Cathleen senses a teachable moment and breaks in. “Talk about charge and spin, Newt.”

“I was going there, Cathleen. Kerr and company’s equations take account of both of those. Turns out the attractive forces between opposite charges are so much stronger than gravity that it’s hard for an object in space to build up a significant amount of either kind of charge without getting neutralized almost immediately. Kind of ironic that the Coulomb force, far stronger than gravity, generates net energy contributions that are much smaller than the gravity‑based ones. Spin, though, that’s where the loopholes are. Penrose figured out how particles from the accretion disk could dip into the black hole’s spinning ergosphere, steal some of its energy, and stream up to power the jets.”

VBOR — “What’s your loophole then?”

“Speed contrast between layers. The black hole mass is spinning at a great rate, dragging nearby spacetime and the ergosphere and the accretion disk around with it. But the layers go slower as you move outward. Station a turbine generator like an idler gear between any two layers and you’re pulling power from the black hole’s spin.”

Silence … then, “Amanda! Amanda! Amanda!”

~ Rich Olcott