It was December, it was cold, no surprise. I unlocked my office door, stepped in and there was Vinnie, standing at the window. He turned to me, shrugged a little and said, “Morning, Sy.” That’s Vinnie for you.

“Morning, Vinnie. What got you onto the streets this early?”

“I ain’t on the streets, I’m up here where it’s warm and you can answer my LIGO question.”

“And what’s that?”

“I read your post about gravitational waves, how they stretch and compress space. What the heck does that even mean?”

floating in a zero-gravity environment,

each depicting a local x, y, and z axis

“Funny thing, I just saw a paper by Professor Saulson at Syracuse that does a nice job on that. Imagine a boxful of something real light but sparkly, like shiny dust grains. If there’s no gravitational field nearby you can arrange rows of those grains in a nice, neat cubical array out there in empty space. Put ’em, oh, exactly a mile apart in the x, y, and z directions. They’re going to serve as markers for the coordinate system, OK?”

“I suppose.”

“Now it’s important that these grains are in free-fall, not connected to each other and too light to attract each other but all in the same inertial frame. The whole array may be standing still in the Universe, whatever that means, or it could be heading somewhere at a steady speed, but it’s not accelerating in whole or in part. If you shine a ray of light along any row, you’ll see every grain in that row and they’ll all look like they’re standing still, right?”

“I suppose.”

“OK, now a gravitational wave passes by. You remember how they operate?”

“Yeah, but remind me.”

(sigh) “Gravity can act in two ways. The gravitational attraction that Newton identified acts along the line connecting the two objects acting on each other. That longitudinal force doesn’t vary with time unless the object masses change or their distance changes. We good so far?”

“Sure.”

“Gravity can also act transverse to that line under certain circumstances. Suppose we here on Earth observe two black holes orbiting each other. The line I’m talking about is the one that runs from us to the center of their orbit. As each black hole circles that center, its gravitational field moves along with it. The net effect is that the combined gravitational field varies perpendicular to our line of sight. Make sense?”

“Gimme a sec… OK, I can see that. So now what?”

“So now that variation also gets transmitted to us in the gravitational wave. We can ignore longitudinal compression and stretching along our sight line. The black holes are so far away from us that if we plug the distance variation into Newton’s F=m1m2/r² equation the force variation is way too small to measure with current technology.

“The good news is that we can measure the off-axis variation because of the shape of the wave’s off-axis component. It doesn’t move space up-and-down. Instead, it compresses in one direction while it stretches perpendicular to that, and then the actions reverse. For instance, if the wave is traveling along the z-axis, we’d see stretching follow compression along the x-axis at the same time as we’d see compression following stretching along the y-axis.”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

“Exactly. You can see how that affects our grain array in this video I just happen to have cued up. See how the up-down and left-right coordinates close in and spread out separately as the wave passes by?”

“Does this have anything to do with that ‘expansion of the Universe’ thing?”

“Well, the gravitational waves don’t, so far as we know, but the notion of expanding the distance between coordinate markers is exactly what we think is going on with that phenomenon. It’s not like putting more frosting on the outside of a cake, it’s squirting more filling between the layers. That cosmological pressure we discussed puts more distance between the markers we call galaxies.”

“Um-hmm. Stay warm.”

(sound of departing footsteps and door closing)

“Don’t mention it.”

~~ Rich Olcott

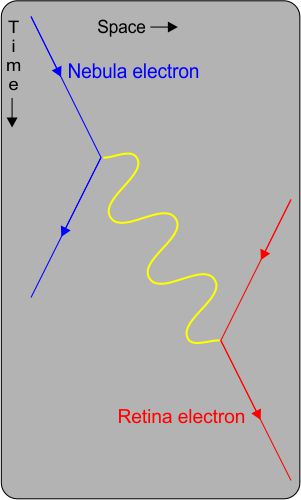

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

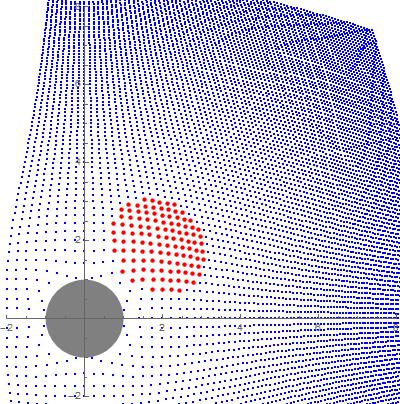

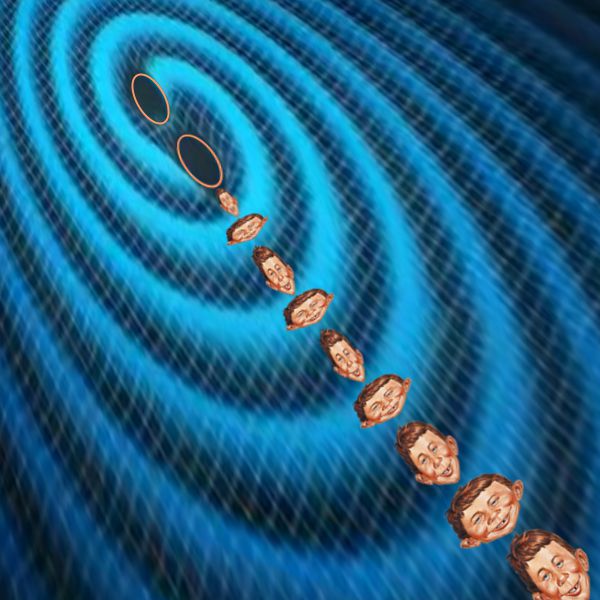

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba).

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba). Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic.

Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic. We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be).

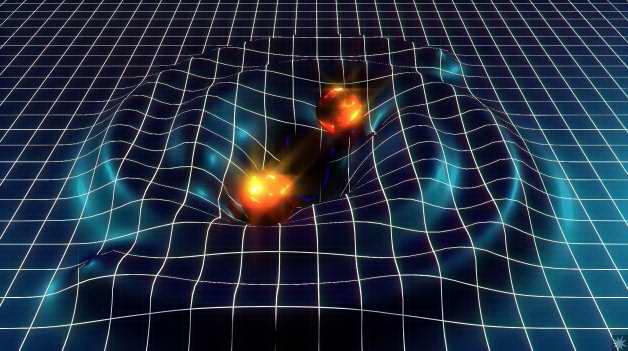

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be). An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See