“Sy, I’m trying to get my head wrapped around how the potential‑kinetic energy thing connects with your enthalpy thing.”

“Alright, Vinnie, what’s your cut so far?”

“It has to do with scale. Big things, like us and planets, we can see things moving and so we know they got kinetic energy. If they’re not moving steady in a straight line we know they’re swapping kinetic energy, give and take, with some kind of potential energy, probably gravity or electromagnetic. Gravity pulls things into a circle unless angular momentum gets in the way. How’m I doing so far?”

“I’d tweak that a little, but nothing to argue with. Keep at it.”

“Yeah, I know the moving is relative to whether we’re in the same reference frame and all that. Beside the point, gimme a break. So anyway, down to the quantum level. Here you say heat makes the molecules waggle so that’s kinetic energy. What’s potential energy like down there?”

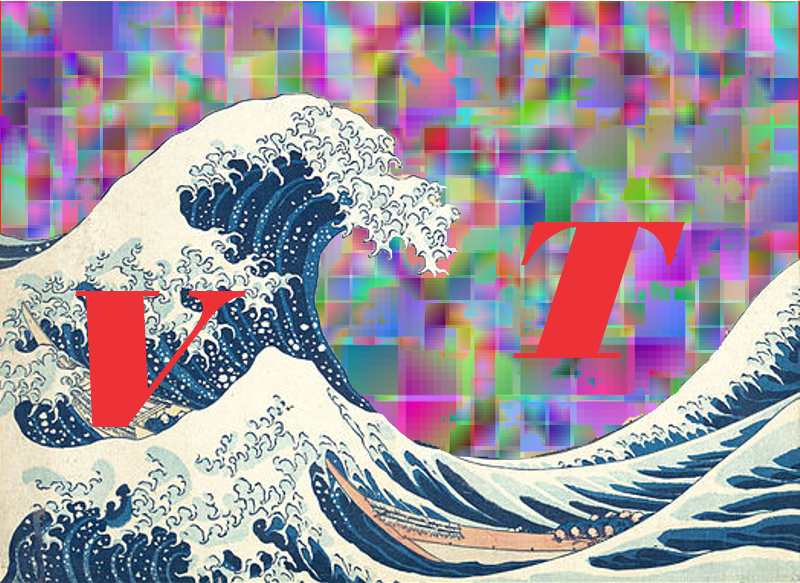

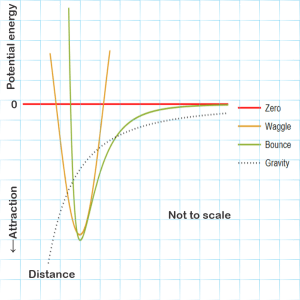

<grabs another paper napkin> “Here’s a quick sketch of the major patterns.”

“Hmm. You give up potential energy when you fall and gravity’s graph goes down from zero to more negative forever, I guess, so gravity’s always attracting.”

“Pretty much, but at this level we don’t have to bother with gravity at all. It’s about a factor of 1038 weaker than electric interactions. Molecular motions are dominated by electromagnetic fields. Some are from a molecule’s other internal components, some from whatever’s around that brandishes a charge. We’ve got two basic patterns. One of them, I’m labeling it ‘Waggle,’ works like a pendulum, sweeping up and down that U‑shape around some minimum position, high kinetic energy where the potential energy’s lowest and vice‑versa. You know how water’s H‑O‑H molecules have that the V‑shape?”

“Yeah, me you and Eddie talked about that once.”

“Mm‑hm. Well, the V‑shape gives that molecule three different ways to waggle. One’s like breathing, both sides out then both sides in. If the hydrogens move too far from the oxygen, that stretches their chemical bonds and increases their potential energy so they turn around and go back. If they get too close, same thing. Bond strength is about the depth of the U. The poor hydrogens just stretch in and out eternally, swinging up and down that symmetric curve.”

“Awww.”

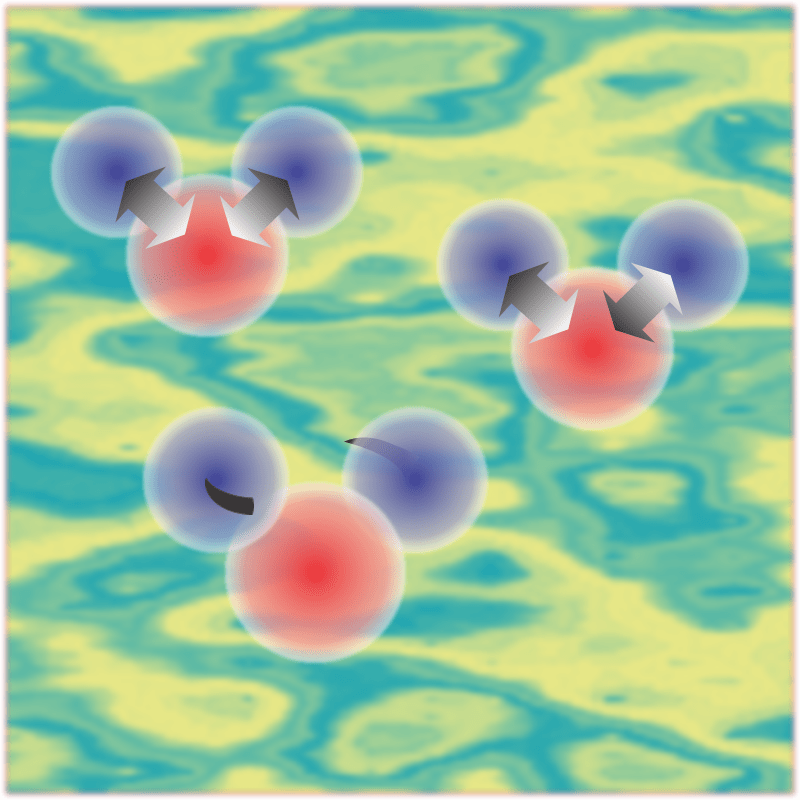

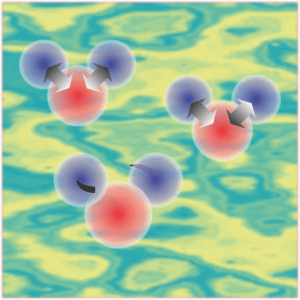

“That’s a chemist’s picture. The physics picture is cloudier. In the quantum version, over here’s a trio of fuzzy quarks whirling around each other to make a proton. Over there’s a slightly different fuzzy trio pirouetting as a neutron. Sixteen of those roiling about make up the oxygen nucleus plus two more for the hydrogens plus all their electrons — imagine a swarm of gnats. On the average the oxygen cloud and the two hydrogen clouds configure near the minimum of that U‑shaped potential curve but there’s a lot of drifting that looks like symmetrical breathing.”

“What about the other two waggles?”

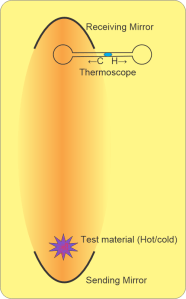

“I knew you’d ask. One’s like the two sides of a teeterboard, oscillating in and out asymmetrically. The other’s a twist, one side coming toward you and then the other side. Each waggle has its own distinct set of resistance forces that define its own version of waggle curve. Each kind interacts with different wavelengths of infrared light which is how we even know about them. Waggle’s official name is ‘harmonic oscillator.’ More complicated molecules have lots of them.”

“What’s that ‘bounce’ curve about?”

“Officially that’s a Lennard-Jones potential, the simplest version of a whole family of curves for modeling how molecules bounce off each other. Little or no interaction at large distances, serious repulson if two clouds get too close, and a little stickiness at some sweet-spot distance. If it weren’t for the stickiness, the Ideal Gas Law would work even better than it does. So has your head wrapped better?”

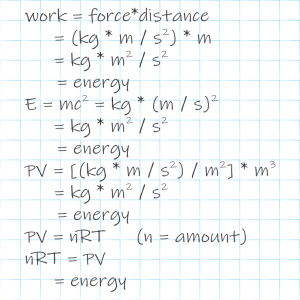

“Sorta. From what I’ve seen, enthalpy’s PV part doesn’t apply in quantum. The heat capacity part comes from your waggles which is kinetic energy even if it’s clouds moving. Coming the other way, quantum potential energy becomes enthalpy’s chemical part with breaking and making chemical bonds. Did I bridge the gap?”

“Mostly, if you insist on avoiding equations.”

~ Rich Olcott