“I got another question, Moire.”

“Of course you do, Mr Feder. Let’s hear it.”

“I read on the Internet that there’s every kind of radioactivity coming out of lightning bolts. So is that true, how’s it happen and how come we’re not all glowing in the dark?”

“Well, now, like much else you read on the Internet there’s a bit of truth in there, and a bit of not-truth, all wrapped up in hype. The ‘every kind of radioactivity’ part, for instance, that’s false.”

“Oh yeah? What’s false about that?”

“Kinds like heavy-atom fission and alpha-particle ejection. Neither have been reported near lightning strikes and they’re not likely to be. Lightning travels through air. Air is 98% nitrogen and oxygen with a sprinkling of light atoms. Atoms like that don’t do those kinds of radioactivity.”

“So what’s left?”

“There’s only two kinds worth worrying about — beta decay, where the nucleus spits out an electron or positron, and some processes that generate gamma-rays. Gamma’s a high-energy photon, higher even than X-rays. Gamma photons are strong enough to ionize atoms and molecules.”

“You said ‘worth worrying about.’ I like worrying. What’s in the not-worth-it bucket?”

“Neutrinos. They’re so light and interact so little with matter that many physicists think of them as just an accounting device. Trillions go through you every second and you don’t notice and neither do they. Really, don’t worry about them.”

“Easy for you to say. Awright, so how does lightning make the … I guess the beta and gamma radioactivity?”

“We know the general outlines, although a lot of details have yet to be filled in. What do you know about linear accelerators?”

“Not a clue. What is one?”

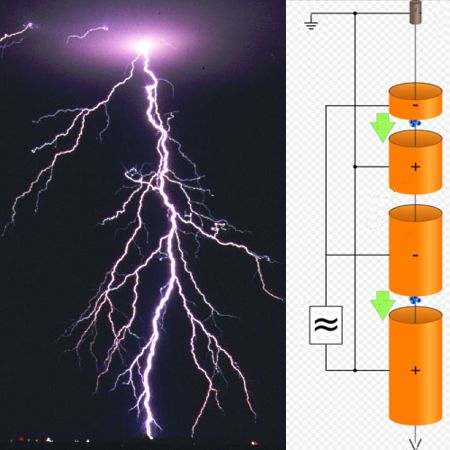

Sgbeer – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

“It’s a technology for making high-energy electrons and other charged particles. Picture a straight evacuated pipe equipped with ring electrodes at various distances from the source end. The source could be an electron gun or maybe a rig that spits out ions of some sort. Voltages between adjacent electrodes downstream of a particle will give it a kick when it passes en route to the target end. By using the right voltages at the right times you can boost an electron’s kinetic energy into the hundred-million-eV range. That’s a lot of kinetic energy. Got that picture?”

“Suppose that I do. Then what?”

“Lightning is the same thing but without the pipe and it’s not straight. The electrons have an evacuated path, because plasma formation drives most of the molecules out of there. Activity inside the clouds gives them high voltages, up to a couple hundred megavolts. But on top of that there’s bremsstrahlung.”

“Brem…?”

“Bremsstrahlung — German for braking radiation. You know how your car’s tires squeal when you make a turn at speed?”

“One of my favorite sounds, ‘specially when … never mind. What about it?”

“That’s your tires converting your forward momentum into sound waves. Electrons do that, too, but with electromagnetism. The lightning path zigs and zags. An electron’s path has to follow suit. At each swerve, the electron throws off some of its kinetic energy as an electromagnetic wave, otherwise known as a photon. Those can be very high-energy photons, X-rays or even gamma-rays.”

“So that’s where the gammas come from.”

“Yup. But there’s more. Remember those nitrogen atoms? Ninety-nine-plus percent of them are nitrogen-14, a nice, stable isotope with seven protons and seven neutrons. If a sufficiently energetic gamma strikes a nitrogen-14, the atom’s nucleus can kick out a neutron and turn into unstable nitrogen-13. That nucleus emits a positron to become stable carbon-13. So you’ve got free neutrons and positrons to add to the radiation list.”

“With all that going on, how come I’m not glowing in the dark?”

“‘Because the radiation goes away quickly and isn’t contagious. Most of the neutrons are soaked up by hydrogen atoms in passing water molecules (it’s raining, remember?). Nitrogen-13 has a 10-minute half-life and it’s gone. The remaining neutrons, positrons and gammas can ionize stuff, but that happens on the outsides of molecules, not in the nuclei. Turning things radioactive is a lot harder to do. Don’t worry about it.”

“Maybe I want to.”

“Your choice, Mr Feder.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

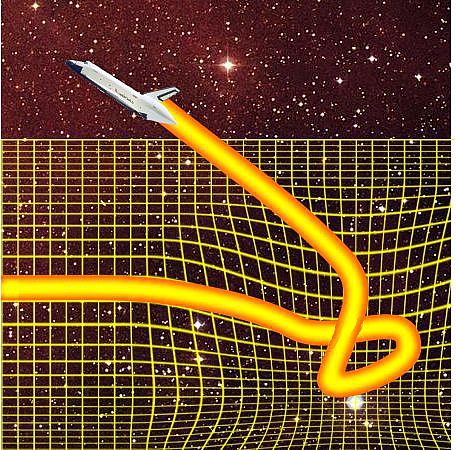

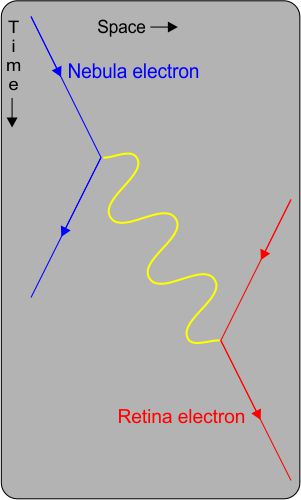

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

But there are other accelerations that aren’t so easily accounted for. Ever ride in a car going around a curve and find yourself almost flung out of your seat? This little guy wasn’t wearing his seat belt and look what happened. The car accelerated because changing direction is an acceleration due to a lateral force. But the guy followed Newton’s First Law and just kept going in a straight line. Did he accelerate?

But there are other accelerations that aren’t so easily accounted for. Ever ride in a car going around a curve and find yourself almost flung out of your seat? This little guy wasn’t wearing his seat belt and look what happened. The car accelerated because changing direction is an acceleration due to a lateral force. But the guy followed Newton’s First Law and just kept going in a straight line. Did he accelerate? Suppose you’re investigating an object’s motion that appears to arise from a new force you’d like to dub “heterofugal.” If you can find a different frame of reference (one not attached to the object) or otherwise explain the motion without invoking the “new force,” then heterofugalism is a fictitious force.

Suppose you’re investigating an object’s motion that appears to arise from a new force you’d like to dub “heterofugal.” If you can find a different frame of reference (one not attached to the object) or otherwise explain the motion without invoking the “new force,” then heterofugalism is a fictitious force.

Gargh, proto-humanity’s foremost physicist 2.5 million years ago, opened a practical investigation into how motion works. “I throw rock, hit food beast, beast fall down yes. Beast stay down no. Need better rock.” For the next couple million years, we put quite a lot of effort into making better rocks and better ways to throw them. Less effort went into understanding throwing.

Gargh, proto-humanity’s foremost physicist 2.5 million years ago, opened a practical investigation into how motion works. “I throw rock, hit food beast, beast fall down yes. Beast stay down no. Need better rock.” For the next couple million years, we put quite a lot of effort into making better rocks and better ways to throw them. Less effort went into understanding throwing. Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with anything so unsystematic. He was just full of theories, many of which got in each other’s way. One theory was that things want to go where they’re comfortable because of what they’re made of — stones, for instance, are made of earth so naturally they try to get back home and that’s why we see them fall downwards (no concrete linkage, so it’s still AAAD).

Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with anything so unsystematic. He was just full of theories, many of which got in each other’s way. One theory was that things want to go where they’re comfortable because of what they’re made of — stones, for instance, are made of earth so naturally they try to get back home and that’s why we see them fall downwards (no concrete linkage, so it’s still AAAD).

I was only 10 years old but already had Space Fever thanks to Chesley Bonestell’s artwork in Collier’s and Life magazines. I eagerly joined the the movie theater ticket line to see George Pal’s Destination Moon. I loved the Woody Woodpecker cartoon (it’s 12 minutes into the

I was only 10 years old but already had Space Fever thanks to Chesley Bonestell’s artwork in Collier’s and Life magazines. I eagerly joined the the movie theater ticket line to see George Pal’s Destination Moon. I loved the Woody Woodpecker cartoon (it’s 12 minutes into the