Back when I was in high school I did a term paper for some class (can’t remember which) ripping the heck out of Superman physics. Yeah, I was that kind of kid. If I recall correctly, I spent much of it slamming his supposed vision capabilities — they were fairly ludicrous even to a HS student and that was many refreshes of the DC universe ago. But for this post let’s consider a trope that’s been taken off the shelf again and again since those days, even in the movies. This rendition should get the idea across — Our Hero, in a desperate effort to fix a narrative hole the writers had dug themselves into, is forced to fly around the Earth at faster-than-light speeds, thereby reversing time so he can patch things up.

But for this post let’s consider a trope that’s been taken off the shelf again and again since those days, even in the movies. This rendition should get the idea across — Our Hero, in a desperate effort to fix a narrative hole the writers had dug themselves into, is forced to fly around the Earth at faster-than-light speeds, thereby reversing time so he can patch things up.

So many problems… Just for starters, the Earth is 8000 miles wide, Supey’s what, 6’6″?, so on this scale he shouldn’t fill even a thousandth of a pixel. OK, artistic license. Fine.

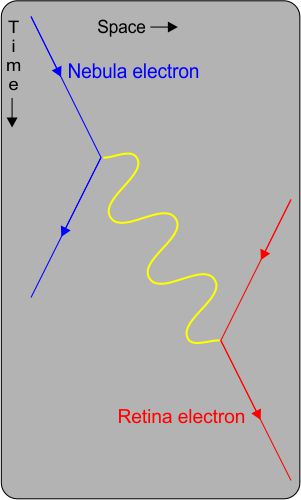

Second problem, only one image of the guy. If he’s really passing us headed into the past we should see two images, one coming in feet-first from the future and the other headed forward in both space and time. Oh, and because of the Doppler effect the feet-first image should be blue-shifted and the other one red-shifted.

Of course both of those images would be the wrong shape. The FitzGerald-Lorentz Contraction makes moving objects appear shorter in the direction of motion. In other words, if the Man of Steel were flying just shy of the speed of light then 6’6″ tall would look to us more like a disk with a short cape.

Tall-Dark-And-Muscular has other problems to solve on his way to the past. How does he get up there in the first place? Back in the day, DC explained that he “leaped tall buildings in a single bound.” That pretty much says ballistic high-jump, where all the energy comes from the initial impulse. OK, but consider the rebound effects on the neighborhood if he were to jump with as much energy as it would take to orbit a 250-lb man. People would complain.

Remember Einstein’s famous E=mc²? That mass m isn’t quite what most people think it is. Rather, it’s an object’s rest mass m0 modified by a Lorentz correction to account for the object’s kinetic energy. In our hum-drum daily life that correction factor is basically 1.00000… When you get into the lightspeed ballpark it gets bigger.

Here’s the formula with the Lorentz correction in red: m=m0/√[1-(v/c)2]. The square root nears zero as Superman’s velocity v approaches lightspeed c. When the divisor gets very small the corrected mass gets very large. If he got to the Lightspeed Barrier (where v=c) he’d be infinitely massive.

So you’ve got an infinite mass circling the Earth about 7 times a second — ocean tides probably couldn’t keep up, but the planet would be shaking enough to fracture the rock layers that keep volcanoes quiet. People would complain.

Of course, if he had that much mass, Earth and the entire Solar System would be orbiting him.

On the E side of Einstein’s equation, Superman must attain that massive mass by getting energy from somewhere. Gaining that last mile/second on the way to infinity is gonna take a lot of energy.

But it’s worse. Even at less than lightspeed, the Kryptonian isn’t flying in a straight line. He’s circling the Earth in an orbit. The usual visuals show him about as far out as an Earth-orbiting spacecraft. A GPS satellite’s stable 24-hour orbit has a 26,000 mile radius so it’s going about 1.9 miles/sec. Superman ‘s traveling about 98,000 times faster than that. Physics demands that he use a powered orbit, continuously expending serious energy on centripetal acceleration just to avoid flying off to Vega again.

The comic books have never been real clear on the energy source for Superman’s feats. Does he suck it from the Sun? I sure hope not — that’d destabilize the Sun and generate massive solar flares and all sorts of trouble.

Not even the DC writers would want Superman to wipe out his adopted planet just to fix up a plot point.

~~ Rich Olcott

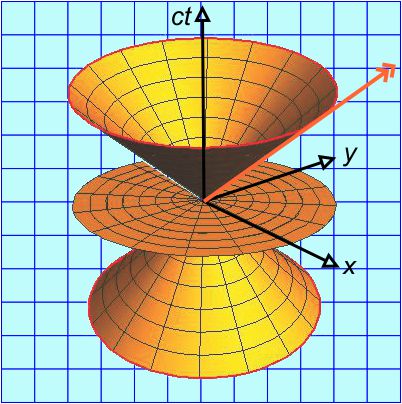

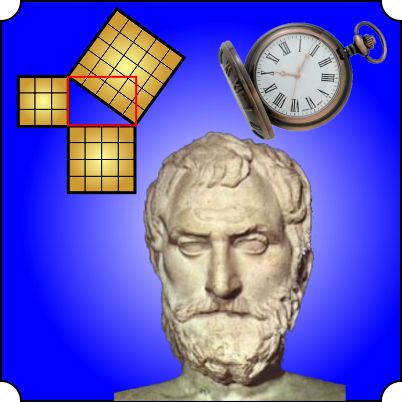

Last week’s Minkowski diagram was two-dimensional. It showed time running along the vertical axis and Pythagorean distance d=√(x²+y²+z²) along the horizontal one. That was OK in the days before computer graphics, but it loaded many different events onto the same point on the chart. For instance, (0,1,0,0), (0,-1,0,0), (0,0,1,0) and (0,0,0,1) (and more) are all at d=1.

Last week’s Minkowski diagram was two-dimensional. It showed time running along the vertical axis and Pythagorean distance d=√(x²+y²+z²) along the horizontal one. That was OK in the days before computer graphics, but it loaded many different events onto the same point on the chart. For instance, (0,1,0,0), (0,-1,0,0), (0,0,1,0) and (0,0,0,1) (and more) are all at d=1.

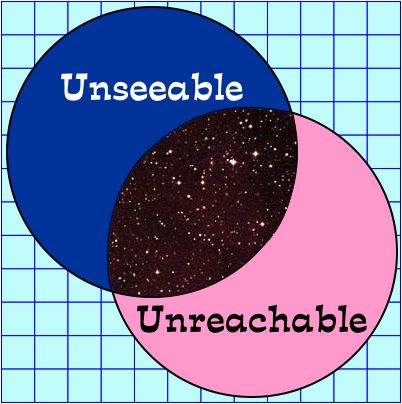

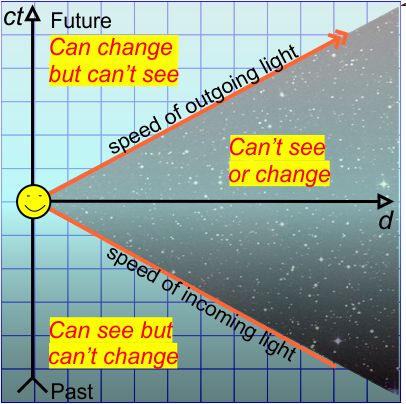

The rest of the Minkowski diagram could do for a Venn diagram. We at (0,0,0,0) can do something that will cause something to happen at (ct,x,y,z) to the left of the top orange line. However, we won’t be able to see that effect until we time-travel forward to its t. That region is “reachable but not seeable.”

The rest of the Minkowski diagram could do for a Venn diagram. We at (0,0,0,0) can do something that will cause something to happen at (ct,x,y,z) to the left of the top orange line. However, we won’t be able to see that effect until we time-travel forward to its t. That region is “reachable but not seeable.”

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

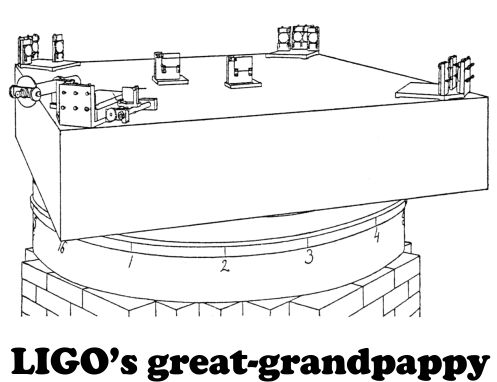

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See