Quite a commotion at the lakeshore this morning. I walk over to see what’s going on. Not surprised at who’s involved. “Come away from there, Mr Feder, you’re too close to their goslings.” Doesn’t work, of course, so I resort to stronger measures. “Hey, Mr Feder, any questions for me?”

That did the trick. “Hey, yeah, Moire, I got one. There’s this big problem with atomic power ’cause there’s leftovers when the fuel’s all used up and nobody wants it buried their back yard and I unnerstand that. How about we just load all that stuff into one of Musk’s Starships and send it off to burn up in the Sun? Or would that make the Sun blow up?”

“Second part first. Do you sneeze?”

“What kinda question is that? Of course I sneeze. Everyone sneezes.”

“Ever been in a hurricane?”

“Oohyeah. Sandy, back in 2012. Did a number on my place in Fort Lee. Took out my back fence, part of the roof, branches down all over the place—”

“Did you sneeze during the storm?”

“Who remembers that sort of thing?”

“If you had, would it have made any difference to how the winds blew?”

“Nah, penny‑ante compared to what else was going on. Besides, the storm eye went a couple hundred miles west of us.”

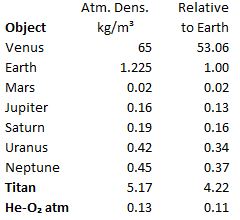

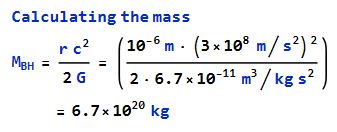

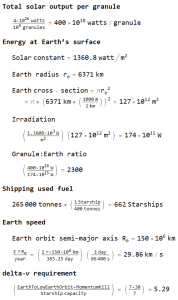

“Well, there you go. The Sun’s surface is covered by about a million granules, each about the size of Texas, and each releasing about 400 exawatts—”.

“Exawha?”

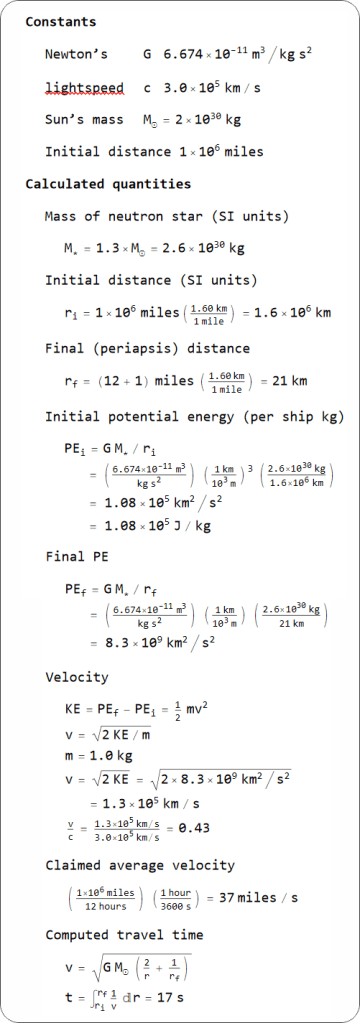

“Exawatt. One watt is one joule of energy per second. Exa– means 1018. So just one of those granules releases 400×1018 joules of energy per second. By my numbers that’s about 2300 times the total energy that Earth gets from the Sun. There’s a million more granules like that. Still think one of our rockets would make much difference with all that going on?”

“No difference anybody’d notice. But that just proves it’d be safe to send our nuclear trash straight to the Sun.”

“Safe, yes, but not practical.”

“When someone says ‘practical’ they’re about to do numbers, right?”

“Indeed. How much nuclear waste do you propose to ship to the Sun?”

“I dunno. How much we got?”

“I saw a 2022 estimate from the International Atomic Energy Agency that our world‑wide accumulation so far is over 265 000 tonnes, mostly spent fuel. Our heaviest heavy‑lift vehicle is the SpaceX Starship. Maximum announced payload to low‑Earth orbit is 400 tonnes for a one‑way trip. You ready to finance 662 launches?”

“Not right now, I’m a little short ’til next payday. How about we just launch the really dangerous stuff, like plutonium?”

“Much easier rocket‑wise, much harder economics‑wise.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Because most of the world’s nuclear power plants depend on MOX fuel, a mixture of plutonium and uranium oxides. Take away all the plutonium, you mess up a significant chunk of our carbon‑free‑mostly electricity production. But I haven’t gotten to the really bad news yet.”

“I’m always good for bad news. Give.”

“Even with the best of intentions, it’s an expensive challenge to shoot a rocket straight from Earth into the Sun.”

“Huh? It’d go down the gravity well just like dropping a ball.”

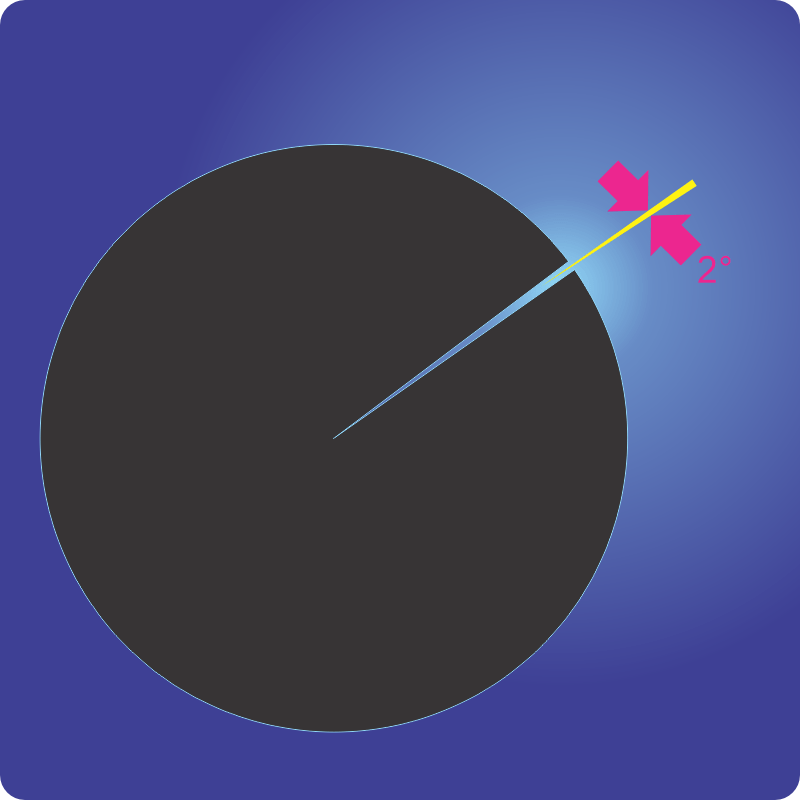

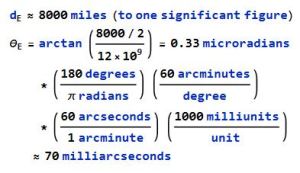

“Nope, not like dropping a ball. More like flinging it off to the side with a badly‑aimed trebuchet. Guess how fast the Earth moves around the Sun.”

“Dunno. I heard it’s a thousand miles an hour at the Equator.”

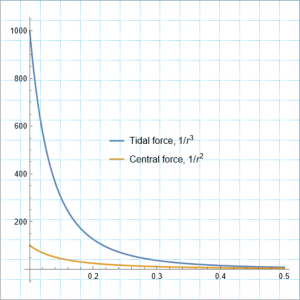

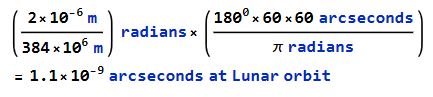

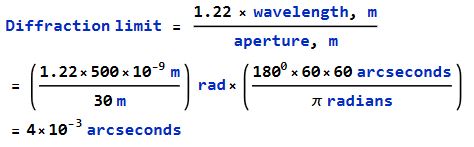

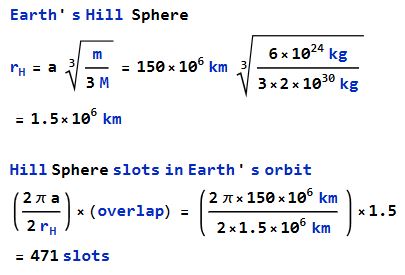

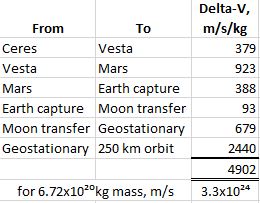

“That’s the planet’s rotation on its own axis. My question was how fast we go taking a year to do an orbit around the Sun. I’ll spare you the arithmetic — the planet speeds eastward at 30 kilometers per second. Any rocket taking off from Earth starts with that vector, and it’s at right angles to the Earth‑Sun line. You can’t hit the Sun without shedding all that lateral momentum. If you keep it, the rules of orbital mechanics force the ship to go faster and faster sideways as it drops down the well — you flat‑out miss the Sun. By the way, LEO delta‑v for SpaceX’s most advanced Starship is about 7 km/s, less than a fifth of the minimum necessary for an Earth‑to‑Sun lift.”

~ Rich Olcott