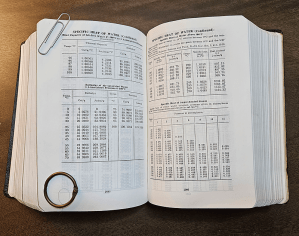

“Wait, Sy. From what you just said about rocket fuel, its enthalpic energy content changes if I move it. On the ground it’s ‘chemical energy plus thermal plus Pressure times Volume.’ Up in space, though, the pressure part’s zero. So how come the CRC Handbook people decided it’s worthwhile to publish pages and pages of specific heat and enthalpy tables if it’s all ‘it depends’?”

“We know the dependencies, Vinnie. The numbers cover a wide temperature range but they’re all at atmospheric pressure. ‘Pressure times Volume‘ makes it easy to adjust for pressure change — just do that multiplication and add the result to the other terms. It’s trickier when the pressure varies between here and there but we’ve got math to handle that. The ‘thermal‘ part’s also not a big problem because if you something’s specific heat you know how its energy content changes with temperature change and vice‑versa.”

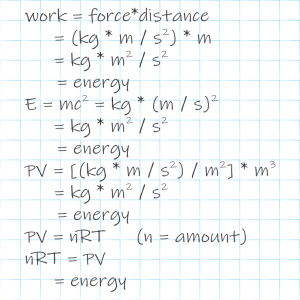

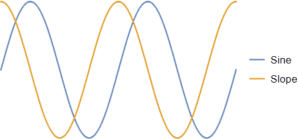

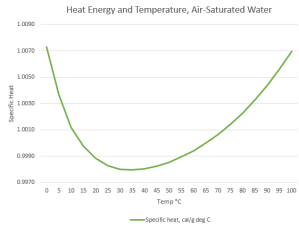

<checking a chart on his phone> “This says water’s specific heat number changes with temperature. They’re all about 1.0 but some are a little higher and some a little lower. Graph ’em out, looks like there’s a pattern there.”

<tapping on Old Reliable’s screen> “Good eye. High at the extreme temperatures, lower near — that’s interesting.”

“What’s that?”

“The range where the curve is flattest, 35 to 40°C. Sound familiar?”

“Yeah, my usual body temperature’s in there, toward the high side if I’ve got a fever. What’s that mean?”

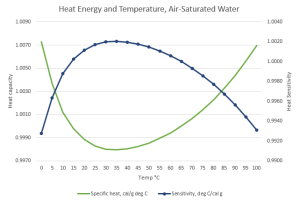

“That’s so far out of my field all I’ve got is guesses. Hold on … there, I’ve added a line for 1/SH.”

“What’s that get you?”

“A different perspective. Specific Heat is the energy change when one gram of something changes temperature by one degree. This new line, I’ve called it Sensitivity, is how many degrees one unit of heat energy will warm the gram. Interesting that both curves flatten out in exactly the temperature range that mammals like us try to maintain. The question is, why do mammals prefer that range?”

“And your answer is?”

“A guess. Remember, I’m not a biologist or a biochemist and I haven’t studied how biomolecules interact with water.”

“I get that we should file this under Crazy Theories. Out with it.”

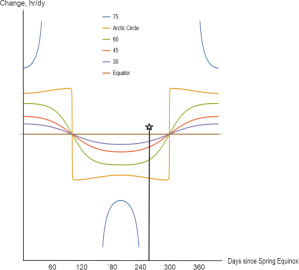

“Okay. Suppose it’s early days in mammalian evolution. You’re one of those early beasties. You’re not cold-blooded like a reptile, you’re equipped with a thermostat for your warm blood. Maybe you shiver if you’re cold, pant if you’re hot, doesn’t matter. What does matter is, your thermostat has a target temperature. Suppose your target’s on the graph’s coolish left side where water’s sensitivity rises rapidly. You’re sunning yourself on a flat rock, all parts of you getting the same calories per hour.”

“That’s on the sunward side. Shady side not so much.”

“Good point. I’ll get to that. On the sunward side you’re absorbing energy and getting warm, but the warmer you get the more your heat sensitivity rises. Near your target point your tissues warm up say 0.4 degree per unit of sunlight, but after some warming those tissues are heating by 0.6 degrees for the same energy input.”

“I recognize positive feedback when I see it, Sy. Every minute on that rock drives me further away from my target temperature. Whoa! But on the shady side I don’t have that problem.”

“That’s even messier. You’ve got a temperature disparity between the two sides and it’s increasing. Can your primitive circulatory system handle that? Suppose you’re smart enough to scurry out of the sunlight. You’ve still got a problem. There’s more to you than your skin. You’ve got muscles and those muscles have cells and those cells do biochemistry. Every chemical reaction inside you gives off at least a little heat for more positive feedback.”

“What if my thermostat’s set over there on the hot side?”

“You’d be happy in the daytime but you’d have a problem at night. For every degree you chill below comfortable, you need to generate a greater amount of energy to get back up to your target setting.”

“Smart of evolution to set my thermostat where water’s specific heat changes least with temperature.”

“That’s my guess.”

~~ Rich Olcott