<THUNK!!> “Oh, dear. Is this the same elevator that you and Vinnie got trapped in, Sy?”

“Afraid so, Cathleen, but at least we had lights. This looks like a power outage, not a stuck door mechanism. Calling the building super probably won’t help. Hope you’re okay being stuck in the dark.”

“I’m an astronomer, Sy. A dark night’s my best thing. Remember the time we got locked with no light in my Mom’s closet?”

<chuckle> “Mm-hm. It was our pretend spaceship to Mars. We had no idea that closet had a catch we couldn’t reach. We were stuck there until your Mom came home. <sigh> We’ll have to wait ’til power comes back.”

<FZzzzzttPOP!!> … <then a voice like molten silver> “Oh, there you are, Sy! I’ve been looking all over for you. Who’s this?”

“Been a while, Anne. This is Cathleen. Cathleen, meet Anne. Anne’s an … explorer.”

“Ooo, where do you explore? For that matter, how did you get in here, and why is your dress (is it satin?) glowing like that?”

“Yes, it is satin, at the moment. It figures out whatever I need and makes that happen. It’s glowing because we’re in the dark.”

“I suspect your dress saved you when you met anti‑Anne.”

“Auntie Anne?”

“No, Cathleen, anti‑Anne, another me in the anti‑Universe. You might be right, Sy. It would have held anti‑Earth’s anti‑atoms away long enough for me to escape annihilation. Maybe I should explain.”

“I wish you would.”

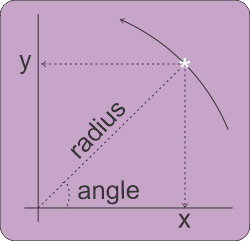

“Wellll, I’ve got this super‑power for jumping across spacetime. Sy helped me calibrate my jumps and we even worked out how I can change size and use entropy to navigate between probabilities. So I explore everywhere and everywhen and that’s how I got into this elevator.” <brief fizzing sound> “Don’t worry, power will be back on soon but we’ve got time for Sy to explain my most recent experience.”

“Ah‑boy, now what?”

“Well, it seemed like a fun thing to do — go back to the earliest time I could, maybe even watch the Big Bang. I did some reading so I had an idea of what to expect as I dove down the time axis — gas clouds collapsing with glittering bursts of star formation, stars collecting into galaxies, galaxies streaming by like granular gas — so beautiful, especially because I can tweak my time rate and watch it all in motion!”

“And did you see all that?”

“Oh, yes, but then I hit a wall I couldn’t get past and I don’t understand why.”

“What were things like just before you hit the wall?”

“This was just beyond when I saw the very first stars turning on. There were vague clouds glowing here and there but basically the Universe became pitch black, no light at all for a while until the background started to glow with a very deep red just before I was blocked.”

“Ah. Cathleen, this is more your bailiwick than mine. Anne, Cathleen teaches Astronomy and Cosmology.”

“Just as a check, Anne, do you know exactly how far into the past you got?”

“Sorry, no. My time sense is pretty well calibrated for hours‑to‑centuries but this was billions of years. You probably know when I was better than I do.”

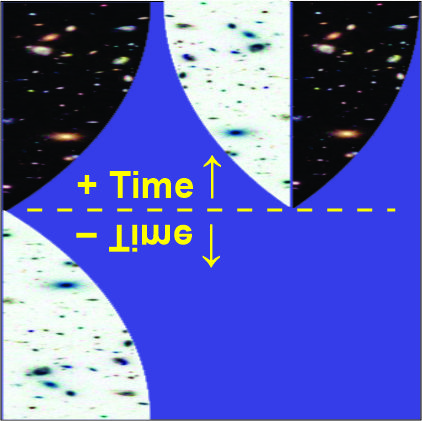

“On the evidence, I’d say you got 99.98% of the way back to your goal, nearly to the beginning of the Dark Age.”

“Dark Age? I’ve been there — 10th‑century Earth, bad times for everyone unless you were at the top of the heap but you wouldn’t stay there long. But I was too far out in space to see Earth. I couldn’t even pick out the Milky Way.”

“No, this was the Universe’s Dark Age, a couple hundred million years between when atoms formed and stars formed. Nothing could make new light. The Dark Age started at Big Bang plus 370 000 years when temperature cooled to 4000 K. The dark red you saw everywhere was atoms emitting blackbody radiation at 4000 K. Just 0.01% further into the past, the Universe was a billion‑degree quark plasma where not even atoms could survive. No wonder your dress wouldn’t let you enter.”

<THUNK!!> “Oh, good, power’s back on. We have light again!”

~ Rich Olcott