Coffee time. I step into Cal’s shop and he’s all over me. ”Sy, have you heard about the the NASA sonification project?”

Susan puts down her mocha latte. “I didn’t like some of what they’ve released. Sounds too much like people screaming.”

Jeremy looks up from the textbook he’s reading. ”In space, no-one can hear you scream.”

Vinnie rumbles from his usual table by the door. “Any of these got anything to do with the Cosmic Hum?”

“They have nothing to do with each other, except they do. Spiral galaxies, too.”

“Huh?”

”Huh?”

”Huh?”

”Huh?”

“A mug of my usual, Cal, please, and a strawberry scone.”

“Sure, Sy, here ya go, but you can’t say something like that around here without you tellin’ us how come.”

“Does the name Bishop Berkeley ring a bell with anyone?”

Vinnie’s on it. ”That the ‘If a tree falls in the forest…‘ guy, right? Claimed there’s no sound unless somebody’s there to hear it?”

“And by extension, no sound outside human hearing range.”

“But bats and them use sound we can’t hear.”

”So do elephants and whales.”

“Well there you go. So are we agreed that he was wrong?”

“Not quite, Mr Moire. His definition of ‘sound‘ was different from one you’d like. He was a philosopher theorizing about perception, but you’re a physicist. You two don’t even define reality the same way.”

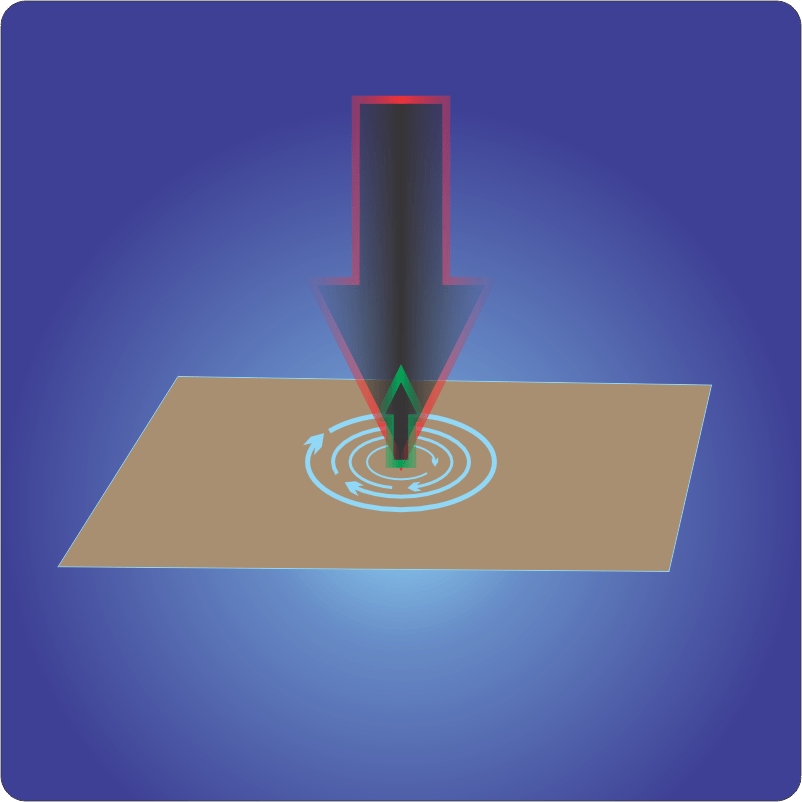

Vinnie’s rumble. ”Good shot, Jeremy. Sound is waves. Sy and me, we talked about them a lot. One molecule bangs into the next one and so on. The molecules don’t move forward, mostly, but the banging does. Sy showed me a video once. So yeah, people listening or not, that tree made a sound. There’s molecules up in space, so there’s sound up there, too, right, Sy?”

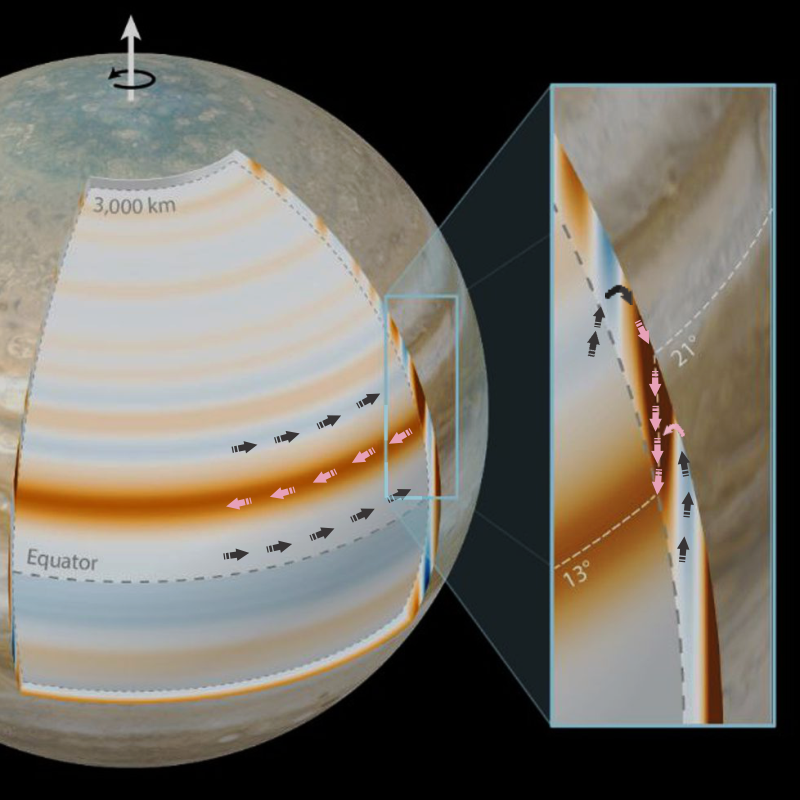

“Mmm, depends on where you are. And what sounds you’re equipped to listen for. The mechanism still works, things advancing a wave by bouncing off each other, but the wave’s length has to be longer than the average distance between the things.” <drawing Old Reliable, pulling up display> “Here’s that video Vinnie saw. I’ve marked two of the particles. You see them moving back and forth over about a wavelength. Suppose a much shorter wave comes along.”

“Umm… Each one would get a forward kick before they got back into position. They wouldn’t oscillate, they’d just keep moving in that direction. No sound wave, just a whoosh.”

“Right, Jeremy. Each out‑of‑sync interaction converts some of the wave’s oscillating energy into one‑way motion. The wave doesn’t get energy back. A dozen wavelengths along, no more wave. So the average distance between particles, we call it the mean free path, sets limits to the length and frequency of a viable wave. Our ears would say it filters out the treble.”

“Space ain’t quite empty so it still has a few atoms to bump together. What kinds of limits do we get out there?”

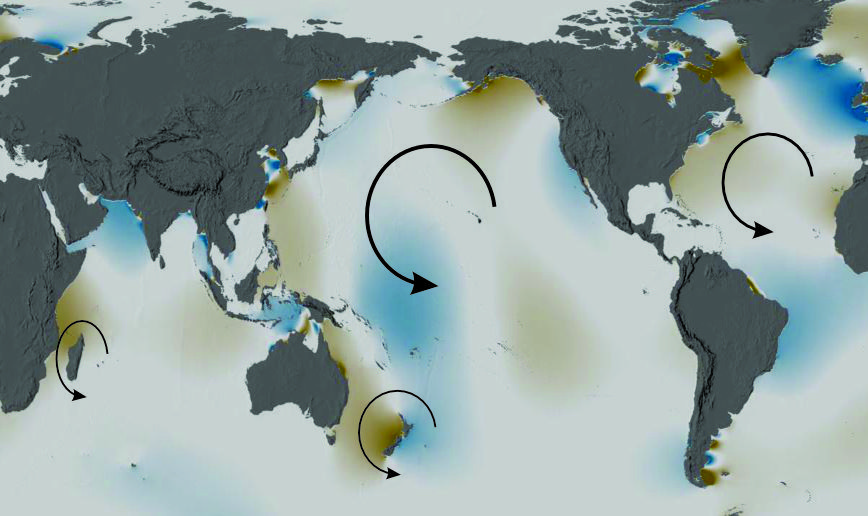

“Well, there’s degrees of empty. Interplanetary space has more atoms per cubic meter than interstellar which is more crowded than intergalactic. Nebulae and molecular clouds can be even less empty. Huge range, but in general we’re talking wavelengths longer than a million kilometers. Frequencies measured in months or years — low even for your voice, Vinnie.”

Jeremy gets a look on his face. ”One of my girlfriends is a soprano. We tested her in the audio lab and she could hit a note just under two kilohertz, that’s two thousand cycles per second. My top screech was below half that. I could scream in space, but I guess not low enough to be heard.”

“Yeah, keep that spacesuit helmet closed and be sure your radio intercom’s working.”

“Wait, what about screaming over the radio?”

“Radio operates with electromagnetic waves, not bumping atoms. Mean free path limits don’t apply. Radio’s frequency range is around a hundred megahertz, screeching’s no problem. Your broadcast equipment’s response range would set your limits.”

“Sy, those screamy sounds I objected to — you say they can’t have traveled across space as sound waves. Was that a radio transmission?”

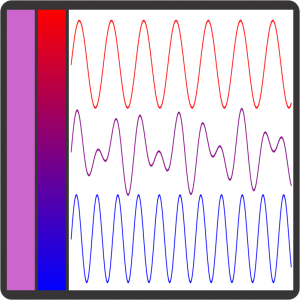

“Maybe, Susan. From what I’ve read, we’ve picked up beaucoodles of radio sources, all different types and all over the sky. Each broadcasts a spectrum of different radio frequencies. Some of them are constant radiators, some vary at different rates. You may have heard a recording of a kilohertz variable source.”

<shudder> “All nasty treble, no bass or harmony.”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Alex, who raised several questions.