Lunch time, so I elbow my way past Feder and head for the elevator. He keeps peppering me with questions.

“Was Einstein ever wrong?”

“Sure. His equations pointed the way to black holes but he thought the Universe couldn’t pack that much mass into that small a space. It could. There are other cases.”

We’re on the elevator and I punch 2. “Where you going? I ain’t done yet.”

“Down to Eddie’s Pizza. You’re buying.”

“Awright, long as I get my answers. Next one — if the force pulling an electron toward a nucleus goes as 1/r², when it gets to where r=0 won’t it get stuck there by the infinite force?”

“No, because at very short distances you can’t use that simple force law. The electron’s quantum wave properties dominate and the charge is a spread-out blur.”

The elevator stops at 7. Cathleen and a couple of her Astronomy students get on, but Feder just peppers on. “So I read that everywhere we look in the Solar System there’s water. How come?”

I look over at Cathleen. “This is Mr Richard Feder of Fort Lee, NJ. He’s got questions. Care to take this one? He’s buying the pizza.”

“Well, in that case. It all starts with alpha particles, Mr Feder.”

The elevator door opens on 2, we march into Eddie’s, order and find a table. “What’s an alpha particle and what’s that got to do with water?”

“An alpha particle’s a fragment of nuclear material that contains two protons and two neutrons. 99.999% of all helium atoms have an alpha particle for a nucleus, but alphas are so stable relative to other possible combinations that when heavy atoms get indigestion they usually burp alpha particles.”

“And the water part?”

“That goes back to where our atoms come from — all our atoms, but in particular our hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen’s the simplest atom, just a proton in its nucleus. That was virtually the only kind of nucleus right after the Big Bang, and it’s still the most common kind. The first generation of stars got their energy by fusing hydrogen nuclei to make helium. Even now, that’s true for stars about the size of the Sun or smaller. More massive stars support hotter processes that can make heavier elements. Umm, Maria, do you have your class notes from last Tuesday?”

“Yes, Professor.”

“Please show Mr Feder that chart of the most abundant elements in the Universe. Do you see any patterns in the second and fourth columns, Mr Feder?”

| Element | Atomic number | Mass % *103 | Atomic weight | Atom % *103 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 1 | 73,900 | 1 | 92,351 |

| Helium | 2 | 24,000 | 4 | 7,500 |

| Oxygen | 8 | 1,040 | 16 | 81 |

| Carbon | 6 | 460 | 12 | 48 |

| Neon | 10 | 134 | 20 | 8 |

| Iron | 26 | 109 | 56 | 2 |

| Nitrogen | 7 | 96 | 14 | <1 |

| Silicon | 14 | 65 | 32 | <1 |

“Hmm… I’m gonna skip hydrogen, OK? All the rest except nitrogen have an even atomic number, and all of ’em except nitrogen the atomic weight is a multiple of four.”

“Bravo, Mr Feder. You’ve distinguished between two of the primary reaction paths that larger stars use to generate energy. The alpha ladder starts with carbon-12 and adds one alpha particle after another to go from oxygen-16 on up to iron-56. The CNO cycle starts with carbon-12 and builds alphas from hydrogens but a slow step in the cycle creates nitrogen-14.”

“Where’s the carbon-12 come from?”

“That’s the third process, triple alpha. If three alphas with enough kinetic energy meet up within a ridiculously short time interval, you get a carbon-12. That mostly happens only while a star’s going nova, simultaneously collapsing its interior and spraying most of its hydrogen, helium, carbon and whatever out into space where it can be picked up by neighboring stars.”

“Where’s the water?”

“Part of the whatever is oxygen-16 atoms. What would a lonely oxygen atom do, floating around out there? Look at Maria’s table. Odds are the first couple of atoms it runs across will be hydrogens to link up with. Presto! H2O, water in astronomical quantities. The carbon atoms can make methane, CH4; the nitrogens can make ammonia, NH3; and then photons from Momma star or somewhere can help drive chemical reactions between those molecules.”

“You’re saying that the water astronomers find on the planets and moons and comets comes from alpha particles inside stars?”

“We’re star dust, Mr Feder.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

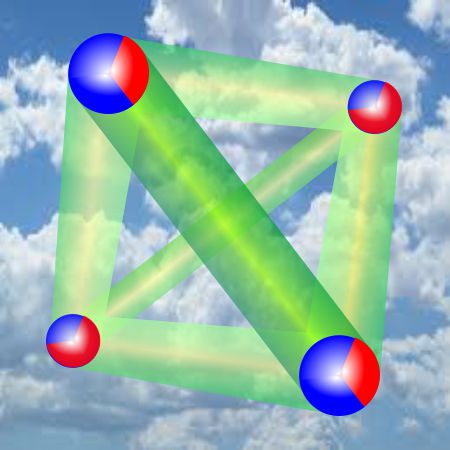

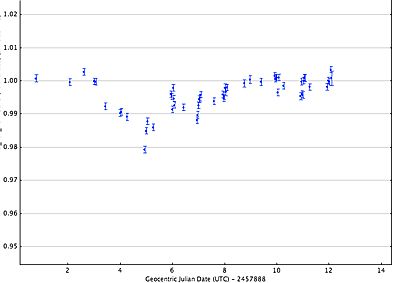

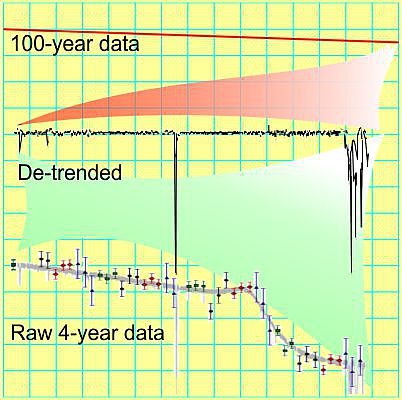

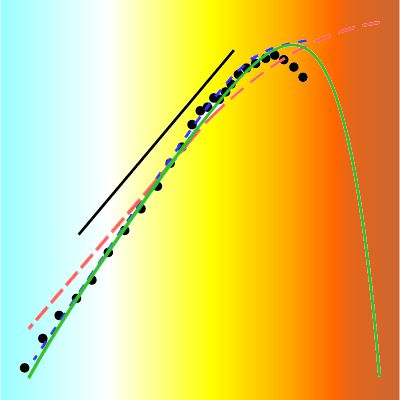

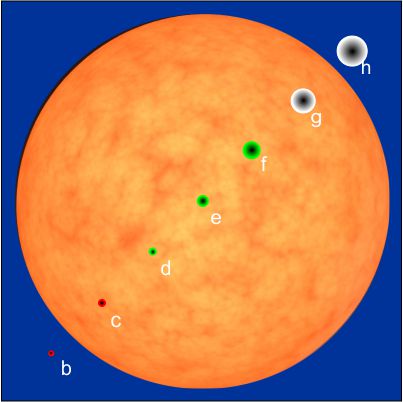

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.”

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.” “How so?”

“How so?”