Now Eddie’s dealing the cards and the topic choice. “So I saw something on TV about a new volcano on Mars. You astronomy guys have been saying Mars is a dead planet, so what’s with a new volcano? Pot’s open.”

Vinnie’s got nothing, throws down his hand. So does Susan, but Kareem antes a few chips. “I doubt there’s a new volcano, it’s probably an old one that we just realized is there. We find a new old caldera on Earth almost every year. Sy, I’ll bet your tablet knows about it.”

I match Kareem’s bet and fire up Old Reliable. A quick search gets me to the news item. “You’re right, Kareem, it’s a new find of an old volcano. This article’s a puff‑piece but the subject’s in your bailiwick, Cathleen.”

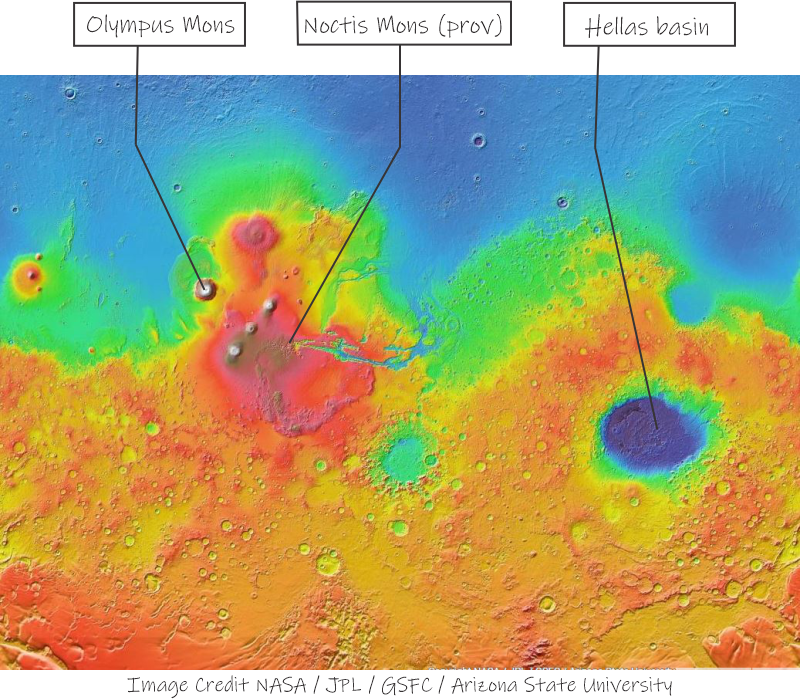

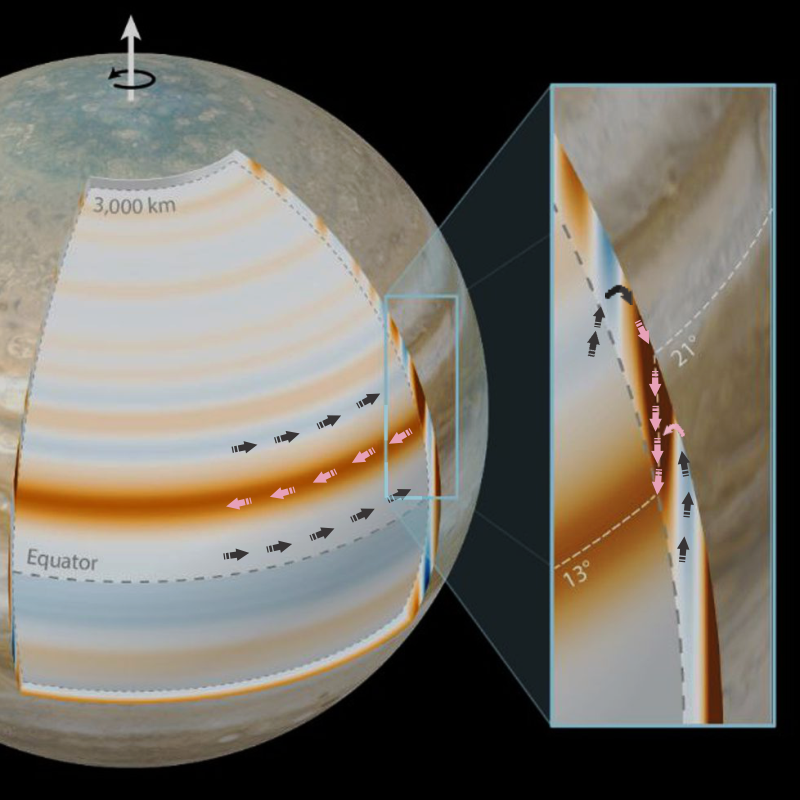

Cathleen puts in her bet and pulls out her tablet. “You’re right, Kareem. It’s a volcano we all saw but no‑one recognized until this two‑person team did. Here’s a wide‑angle view of Mars to get you oriented. North is up top, east is to the right just like usual.”

“Gaah. Looks like a wound!”

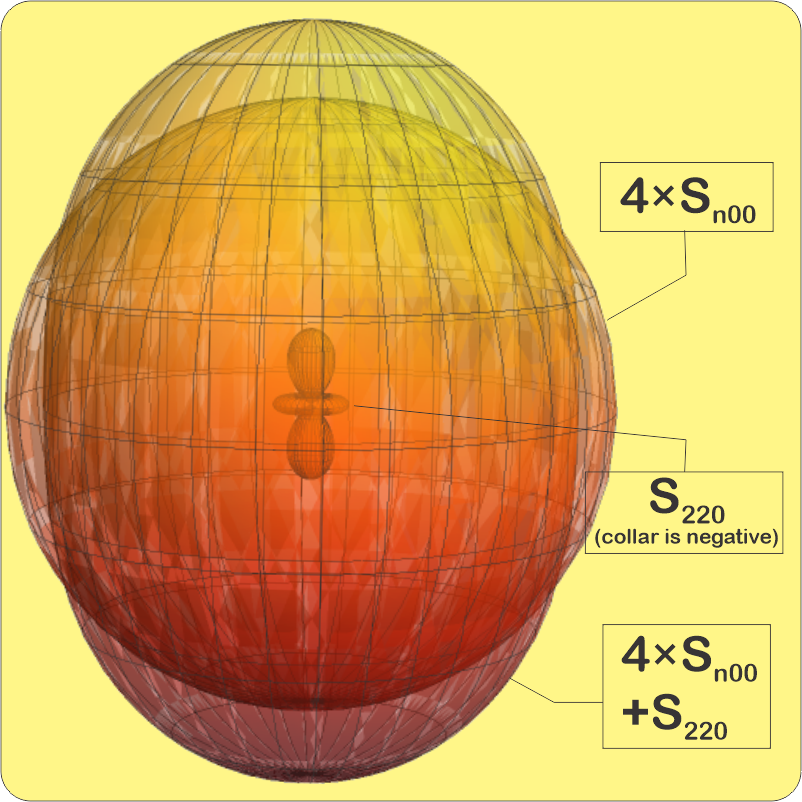

“We’ll get to that. The colors code for elevation, purple for lowlands up through the rainbow to red, brown and white. Y’all know about Olympus Mons, the 22‑kilometer tallest volcano in the Solar System, and there’s Valles Marineris, at 4000 kilometers the longest canyon. The Tharsis bulge is red‑to‑pink because it’s higher than most all the rest of the planet’s surface. Do you see the hidden volcano?”

“It’s hard to tell the volcanos from the meteor craters.”

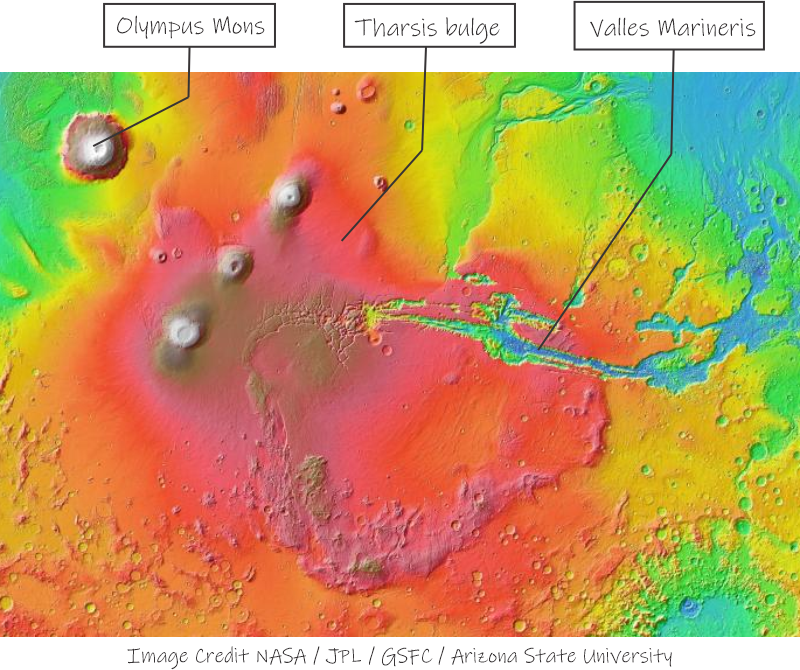

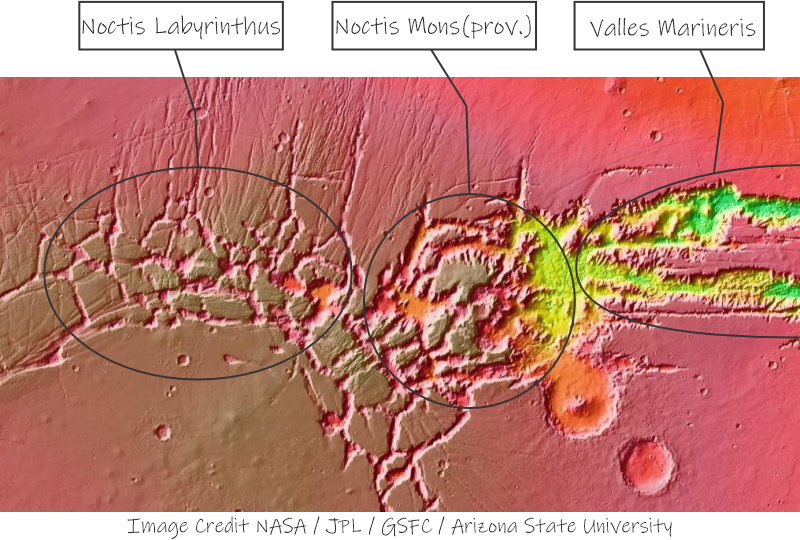

“Understandable. Let me switch to a closer view of the canyon’s western end. This one’s in visible light, no color‑coding games. The middle one of the three Tharsis volcanos is to the left, no ginormous meteor craters in the view. Noctis labyrinthus, ‘the Labyrinth of Night.’ is that badlands region left of center. Lots of crazy canyons that go helter‑skelter.”

“That’s more Mars‑ish, but it’s still unhealthy‑looking.”

“It is a bit rumpled. Do you see the volcano?”

“Mmm, no.”

“This should help. It’s a close-up using the elevation colors to improve contrast.”

“Wow, the area inside that circle sure does look like it’s organized around its center, not higgledy-piggledy like what’s west of it. That brown image had something peaky right about there. What’s ‘prov’?”

“Good eye, Susan. The ‘prov’ means ‘provisional‘ because names aren’t real until the International Astronomical Union blesses them. The peak is nine kilometers high, almost half the height of Olympus Mons. The concentric array of canyons and mesas around it certainly make it look like a collapsed and eroded volcano. But IAU demands more evidence than just ‘look like.’ Using detailed spectroscopic data from two different Mars orbiters, the team found evidence of hydrated minerals plus structural indications that their proposed volcano either punched through a glacier or flowed onto one. Better yet, the mesas all tilt away from the peak, and the minerals are what you’d expect from water reacting with fresh lava.”

“Did they use the word ‘ultramafic‘?”

“I don’t think so, Kareem, just ‘mafic‘.”

“From underground but not deep down, then.”

“I suppose.”

Cal bets. “You said we’d get back to wounds. What was that about?”

“Well, just look at all that mess related to the Tharsis bulge — higher than all its surroundings, massive volcanos nearby, the Noctis badlands, Valles Marineris that doesn’t look water‑carved but has that delta at its eastern end. Why is all of that clustered in just one part of the planet? Marsologists have dozens of hypotheses. My own favorite centers on Hellas basin. It’s the third largest meteor strike in the Solar System and just happens to be almost exactly on the opposite side of Mars.”

Eddie looks a bit gobsmacked. “A wallop like that would carry a lot of momentum. Kareem, can a planet’s interior just pass that along in a straight line?”

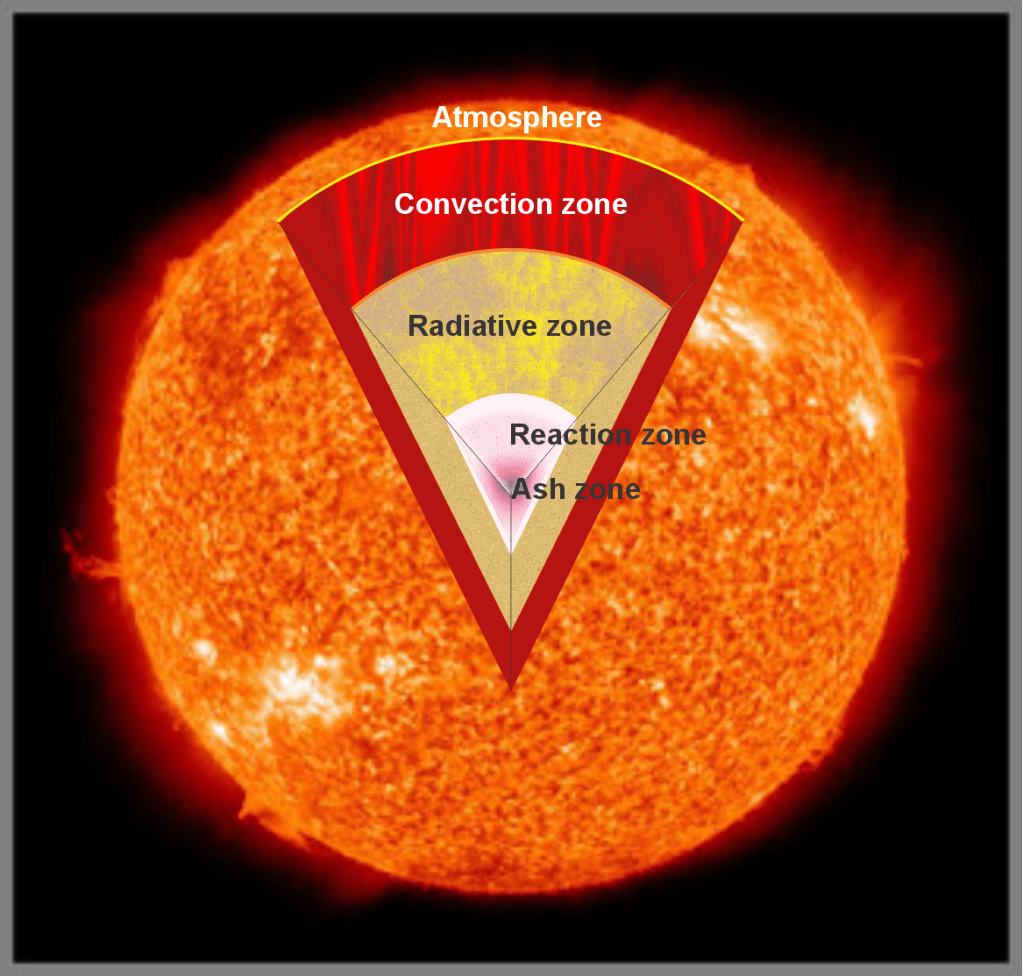

“Could be, depending. If it’s solid or high‑viscosity, I guess so. If it’s low‑viscosity you’d get a doughnut‑shaped circulatory pattern inside that’d turn the energy into heat and vulcanism. How long was Mars cooling before the hit?”

“We don’t know.”

Cal’s pair of jacks apologetically takes the pot.

~~ Rich Olcott