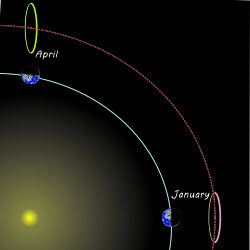

Mr Feder has a snarky grin on his face and a far‑away look in his eye. “Got another one. James Webb Space Telescope flies in this big circle crosswise to the Sun‑Earth line, right? But the Earth doesn’t stand still, it goes around the Sun, right? The circle keeps JWST the same distance from the Sun in maybe January, but it’ll fly towards the Sun three months later and get flung out of position.” <grabs a paper napkin> “Lemme show you. Like this and … like this.”

“Sorry, Mr Feder, that’s not how either JWST or L2 works. The satellite’s on a 6-month orbit around L2 — spiraling, not flinging. Your thinking would be correct for a solid gyroscope but it doesn’t apply to how JWST keeps station around L2. Show him, Sy.”

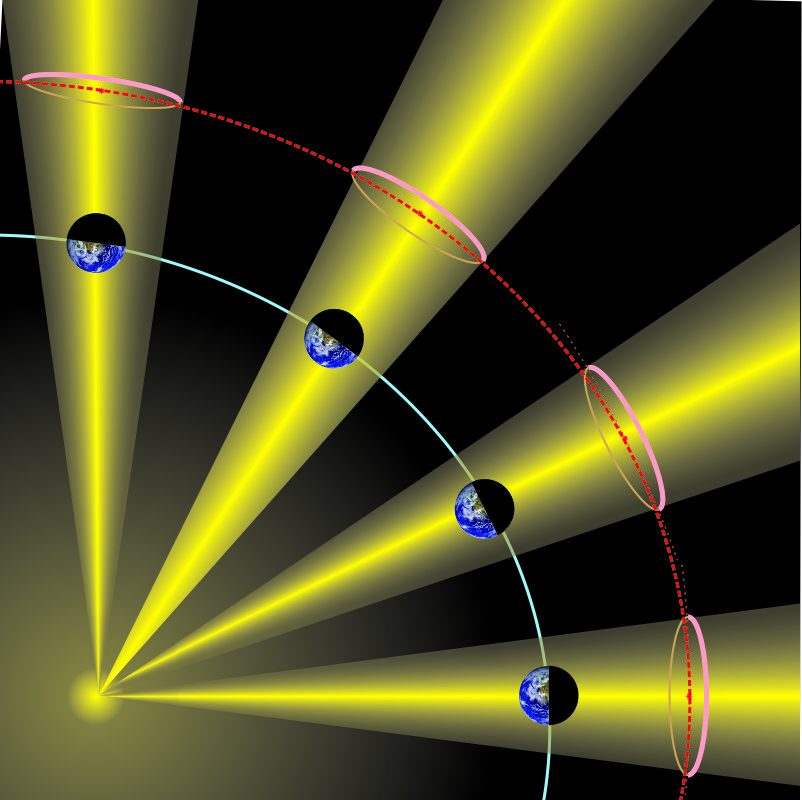

“Gimme a sec with Old Reliable, Cathleen.” <tapping> “OK, here’s an animation over a few months. What happens to JWST goes back to why L2 is a special point. The five Lagrange points are all about balance. Near L2 JWST will feel gravitational pulls towards the Sun and the Earth, but their combined attraction is opposed by the centrifugal force acting to move the satellite further out. L2 is where the three balance out radially. But JWST and anything else near the extended Sun‑Earth line are affected by an additional blended force pointing toward the line itself. If you’re close to it, sideways gravitational forces from the Sun and the Earth combine to attract you back towards the line where the sideways forces balance out. Doesn’t matter whether you’re north or south, spinward or widdershins, you’ll be drawn back to the line.”

Al’s on refill patrol, eavesdropping a little of course. He gets to our table, puts down the coffee pot and pulls up a chair. “You’re talking about the JWST. Can someone answer a question for me?”

“We can try.”

”What’s the question?”

Mr Feder, not being the guy asking the question, pooches out his lower lip.

“OK, how do they get it to point in the right direction and stay there? My little backyard telescope gives me fits just centering on some star. That’s while the tripod’s standing on good, solid Earth. JWST‘s out there standing on nothing.”

“JWST‘s Attitude Control System has a whole set of functions to do that. It monitors JWST‘s current orientation. It accepts targeting orders for where to point the scope. It computes scope and satellite rotations to get from here to there. Then it revises as necessary in case the first‑draft rotations would swing JWST‘s cold side into the sunlight. It picks a convenient guide star from its million‑star catalog. Finally, ACS commands its attitude control motors to swing everything into the new position. Every few milliseconds it checks the guide star’s image in a separate sensor and issues tweak commands to keep the scope in proper orientation.”

“I get the sequence, Sy, but it doesn’t answer the how. They can’t use rockets for all that maneuvering or they’d run out of fuel real fast.”

“Not to mention cluttering up the view field with exhaust gases.”

“Good point, Cathleen. You’re right, Al, they don’t use rockets, they use reaction wheels, mostly.”

“Uh-oh, didn’t broken reaction wheels kill Kepler and a few other missions?”

“That sounds familiar, Mr Feder. What’s a reaction wheel, Sy, and don’t they put JWST in jeopardy?”

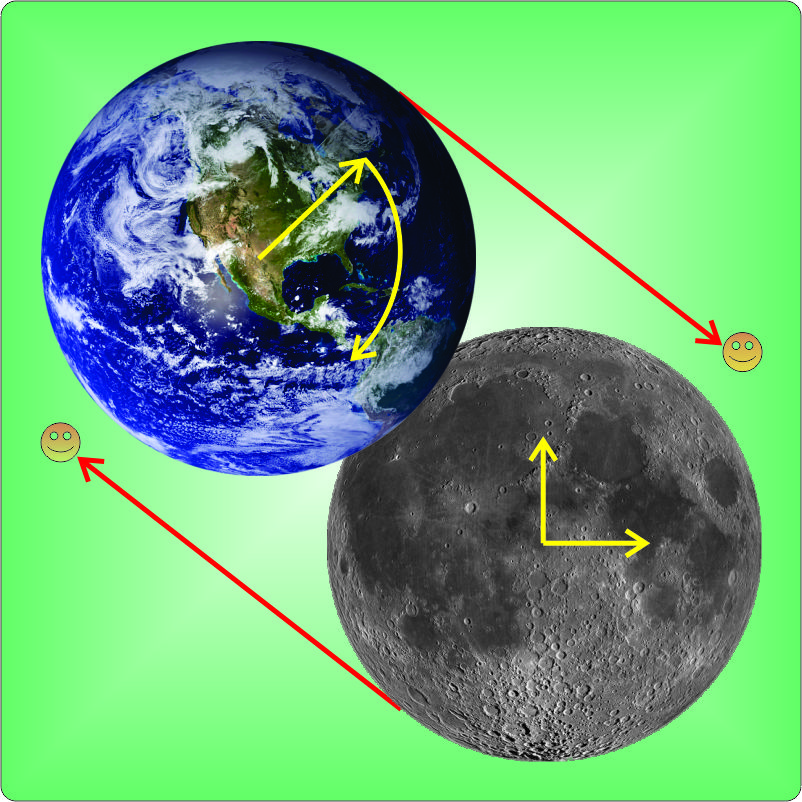

“A reaction wheel is a massive doughnut that can spin at high speed, like a classical gyroscope but not on gimbals.”

“Hey, Moire, what’s a gimbal?”

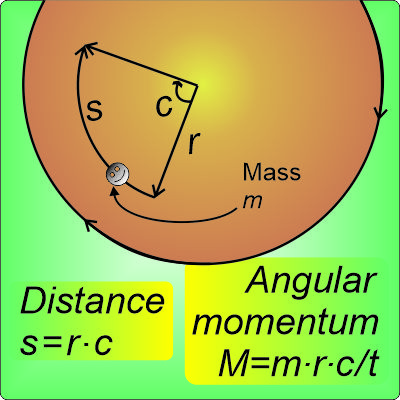

“It’s a rotating frame with two pivots for something else that rotates. Two or three gimbals at mutual right angles let what’s inside orient independent of what’s outside. The difference between a classical gyroscope and a reaction wheel is that the gyroscope’s pivots rotate freely but the reaction wheel’s axis is fixed to a structure. Operationally, the difference is that you use a gyroscope’s angular inertia to detect change of orientation but you push against a reaction wheel’s angular inertia to create a change of orientation.”

“What about the jeopardy?”

“Kepler‘s failing wheels used metal bearings. JWST‘s are hardened ceramic.”

<whew>

~~ Rich Olcott