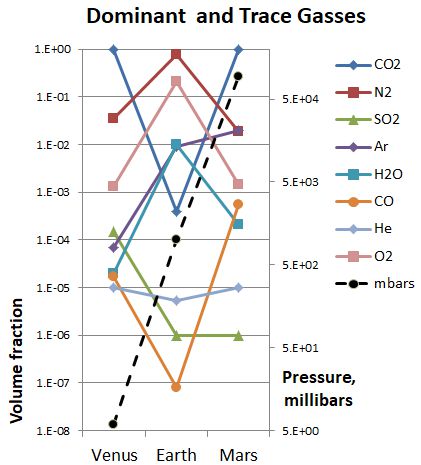

Cathleen’s talking faster near the end of the class. “OK, we’ve seen how Venus, Earth and Mars all formed in the same region of the protosolar disk and have similar overall compositions. We’ve accounted for differences in their trace gasses. So how come Earth’s nitrogen-oxygen atmosphere is so different from the CO2-nitrogen environments on Venus and Mars? Let’s brainstorm — shout out non-atmospheric ways that Earth is unique. I’ll record your list on Al’s whiteboard.”

“Oceans!”

“Plate tectonics!”

“Photosynthesis!”

“Limestone!”

“The Moon!”

“Wombats!” (That suggestion gets a glare from Cathleen. She doesn’t write it down.)

“Goldilocks zone!”

“Magnetic field!”

“People!”

She registers the last one but puts parentheses around it. “This one’s literally a quickie — real-world proof that human activity affects the atmosphere. Since the 1900s gaseous halogen-carbon compounds have seen wide use as refrigerants and solvents. Lab-work shows that these halocarbons catalyze conversion of ozone to molecular oxygen. In the 1970s satellite data showed a steady decrease in the upper-atmosphere ozone that blocks dangerous solar UV light from reaching us on Earth’s surface. A 1987 international pact banned most halocarbon production. Since then we’ve seen upper-level ozone concentrations gradually recovering. That shows that things we do in quantity have an impact.”

“How about carbon dioxide and methane?”

“That’s a whole ‘nother topic we’ll get to some other day. Right now I want to stay on the Mars-Venus-Earth track. Every item on our list has been cited as a possible contributor to Earth’s atmospheric specialness. Which ones link together and how?”

Astronomer-in-training Jim volunteers. “The Moon has to come first. Moon-rock isotope data strongly implies it condensed from debris thrown out by a huge interplanetary collision that ripped away a lot of what was then Earth’s crust. Among other things that explains why the Moon’s density is in the range for silicates — only 60% of Earth’s density — and maybe even why Earth is more dense than Venus. Such a violent event would have boiled off whatever atmosphere we had at the time, so no surprise the atmosphere we have now doesn’t match our neighbors.”

Astrophysicist-in-training Newt Barnes takes it from there. “That could also account for why only Earth has plate tectonics. I ran the numbers once to see how the Moon’s volume matches up with the 70% of Earth’s surface that’s ocean. Assuming meteor impacts grew the Moon by 10% after it formed, I divided 90% of the Moon’s present volume by 70% of Earth’s surface area and got a depth of 28 miles. That’s nicely within the accepted 20-30 mile range for depth of Earth’s continental crust. It sure looks like our continental plates are what’s left of the Earth’s original crust, floating about on top of the metallic magma that Earth held onto.”

Jeremy gets excited. “And the oceans filled up what the continents couldn’t spread over.”

“That’s the general idea.”

Al’s not letting go. “But why does Earth have so much water and why is it the only one of the three with a substantial magnetic field?”

Cathleen breaks in. “The geologists are still arguing about whether Earth’s surface water was delivered by billions of incoming meteorites or was expelled from deep subterranean sources. Everyone agrees, though, that our water is liquid because we’re in the Goldilocks zone. The water didn’t steam away as it probably did on Venus, or freeze below the surface as it may have on Mars. Why the magnetic field? That’s another ‘we’re still arguing‘ issue, but we do know that magnetic fields protect Earth and only Earth from incoming solar wind.”

“So we’re down to photosynthesis and … limestone?”

“Photosynthesis was critical. Somewhere around two billion years ago, Earth’s sea-borne life-forms developed a metabolic pathway that converted CO2 to oxygen. They’ve been running that engine ever since. If Earth ever did have CO2 like Venus has, green things ate most of it. Some of the oxygen went to oxidizing iron but a lot was left over for animals to breathe.”

“But what happened to the carbon? Wouldn’t life’s molecules just become CO2 again?”

“Life captures carbon and buries it. Chalky limestone, for instance — it’s calcium carbonate formed from plankton shells.”

Jim grins. “We owe it all to the Moon.”

~~ Rich Olcott

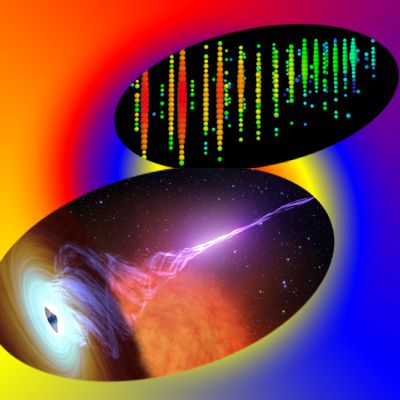

“Half an eV? That’s all? So how come the Big Guy’s got gazillions of eV’s?”

“Half an eV? That’s all? So how come the Big Guy’s got gazillions of eV’s?” “That infinity sign at the bottom means ‘as big as you want.’ So to answer your first question, there isn’t a maximum neutrino energy. To make a more energetic neutrino, just goose it to go even closer to the speed of light.”

“That infinity sign at the bottom means ‘as big as you want.’ So to answer your first question, there isn’t a maximum neutrino energy. To make a more energetic neutrino, just goose it to go even closer to the speed of light.”

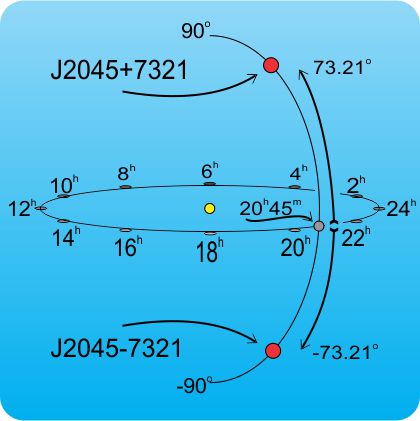

“Wait, right ascension in hours-minute-seconds but declination in degrees?”

“Wait, right ascension in hours-minute-seconds but declination in degrees?”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”