Eddie serves a good pizza. I amble over to the gelato stand for a chaser. “Evening, Jeremy. You’re looking a little distraught.”

“I am, Mr Moire. Just don’t ask me to quantify it! Math is getting me down. Why do they shove so much of it at us? You don’t put much math into your posts and they make sense mostly.”

“Thanks for the mostly. … Do you enjoy poetry?”

“Once I read some poems I liked. Except in English class. They spend too much time classifying genre and rhyme scheme instead of just looking at what the poet wrote. All that gets in the way.”

“Interesting. What is it that you like about poetry?”

“Mmm, part of it is how it can imply things without really saying them, part of it is how compact a really good one is. I like when they cram the maximum impact into the fewest possible words — take out one word and the whole thing falls apart. That’s awesome when it works.”

“Well, how does it work?”

“Oh, there’s lots of techniques. Metaphor’s a biggie — making one thing stand for something else. Word choice, too — an unexpected word or one with several meanings. Sometimes it’s a challenge finding the word that has just the right rhythm and message.”

“Ah, you write, too. When you compose something, do you use English or Navajo?”

“Whichever fits my thought better. Each language is better at some things, worse at others. A couple of times I’ve used both together even though only rez kids would understand the mix.”

“Makes sense. You realize, of course, that we’ve got a metaphor going here.”

“We do? What standing for what?”

“Science and Poetry. I’ve often said that Physics is poetry with numbers. Math is as much a language as English and Navajo. It has its own written and spoken forms just like they do and people do poetry with it. Like them, it’s precise in some domains and completely unable to handle others. Leaning math is like learning a very old language that’s had time to acquire new words and concepts. No wonder learning it is a struggle.”

“Poetry in math? That’s a stretch, Mr Moire.”

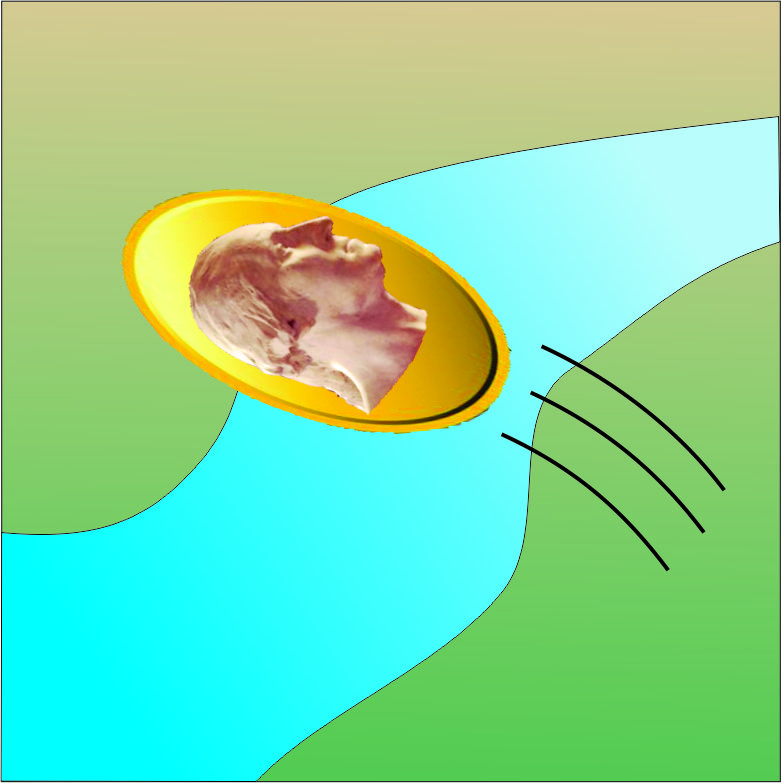

“Prettiest example I can think of quickly is rhyming between the circular and hyperbolic trigonometric systems. The circular system’s based on the sine and cosine. The tangent and such are all built from them.”

“We had those in class — I’ll remember ‘opposite over hypotenuse‘ forever and I got confused by all the formulas — but why do you call them circular and what’s ‘hyperbolic‘ about?”

“Here, let me use Ole Reliable to show you some pictures. I’m sure you recognize the wavy sine and cosine graphs in the circular system. The hyperbolic system is also based on two functions, ‘hyperbolic sine‘ and ‘hyperbolic cosine,’ known in the trade as ‘sinh‘ and ‘cosh.’ They don’t look very similar to the other set, do they?”

“Sure don’t.”

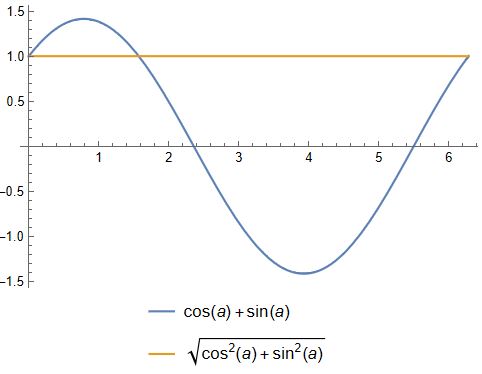

“But for every circular function and formula there’s a hyperbolic partner. Now watch what happens when we combine a sine and cosine. I’ll do it two ways, a simple sum and the Pythagorean sum.”

“Pythagorean?”

“Remember his a2+b2=c2? The orange curve comes from that, see in the legend underneath?”

“Oh, like a right triangle’s hypotenuse. But the orange curve is just a flat straight line.”

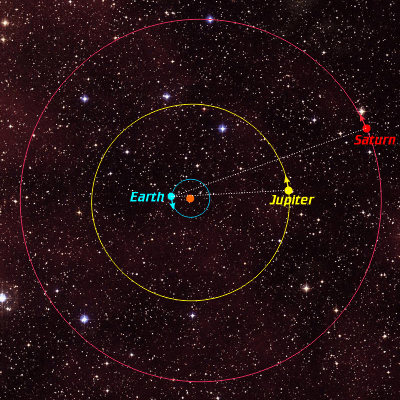

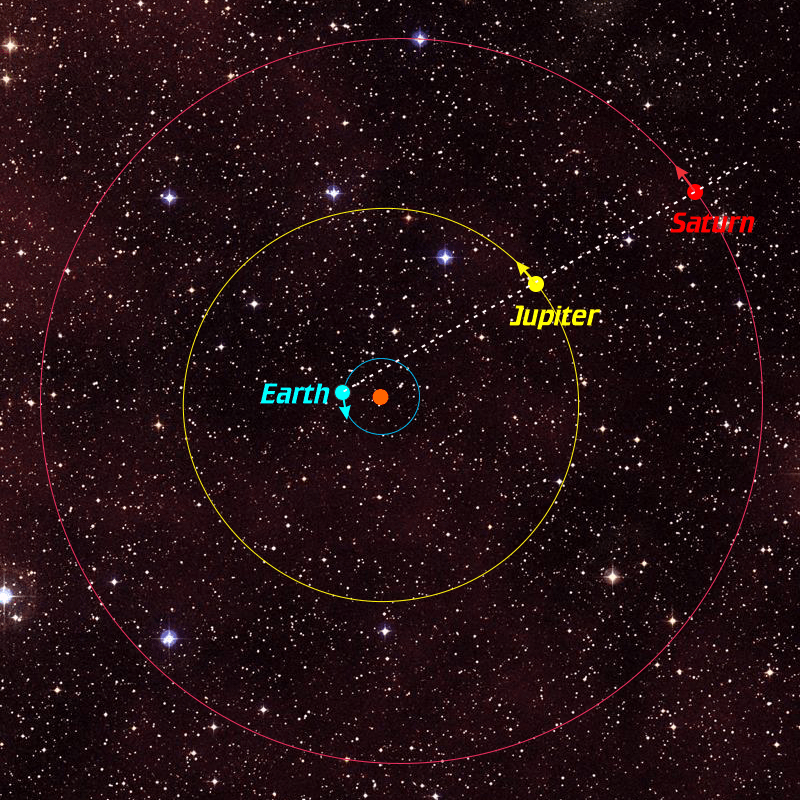

“True, as we’ve known since Euler’s day. Are you familiar with polar coordinates?”

“A little. There’s a center, one coordinate is distance from the center, and the other coordinate is the angle you’ve rotated something, right?”

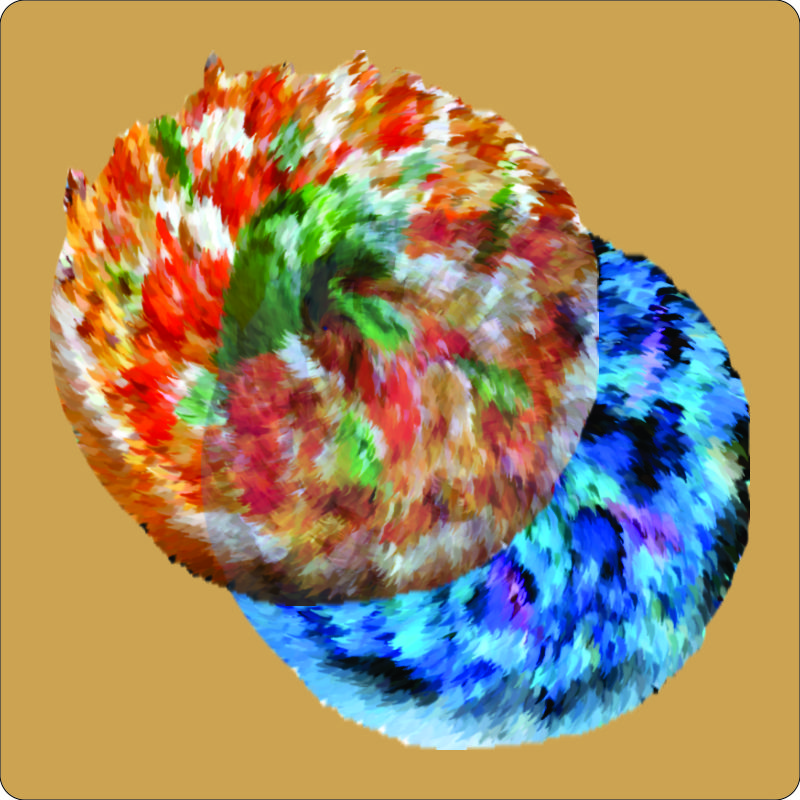

“Good enough. Here’s what the same two combinations look like in polar coordinates..”

“Wow. Two circles. I never would have guessed that.”

“Mm-hm. Check the orange circle, the one that was just a level straight line on the simple graph. It’s centered on the origin. That tells us the sum of the squares is invariant, doesn’t change with the angle.”

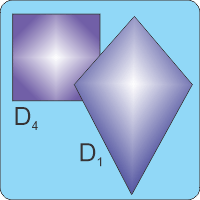

“Do the hyperbolic thingies make hyperbolas when you add them that way?”

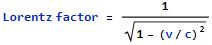

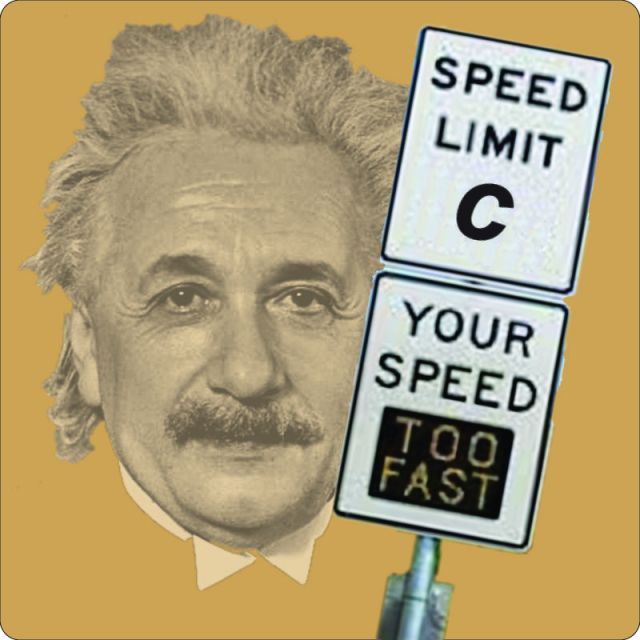

“Not really, just up-curving lines. The plots for their differences are interesting though. For these guys the Pythagorean difference is invariant. Einstein’s relativity is based on that property.”

“Pretty, like you say.”

~~ Rich Olcott

hi, Sy. taking orders for tonite’s delivery. u want pizza? calzone?

hi, Sy. taking orders for tonite’s delivery. u want pizza? calzone?