Vinnie finishes his double‑pepperoni pizza. “Sy, these enthalpies got a pressure‑volume part and a temperature‑heat capacity part, but seems to me the most important part is the chemical energy.”

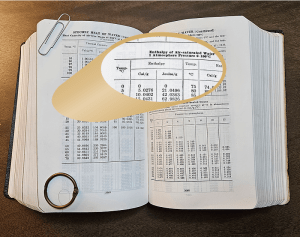

I’m still working on my slice (cheese and sausage). “That’s certainly true from a fuel engineering perspective, Vinnie. Here’s a clue. Check the values in this table for 0°C, also known as 273K.”

“Waitaminute! That line says the enthalpy’s exactly zero under the book‘s conditions. We talked about zeros a long time ago. All measurements have error. Nothing’s exactly zero unless it’s defined that way or it’s Absolute Zero temperature and we’ll never get there. Is this another definition thing?”

“More of a convenience thing. The altimeters in those planes you fly, do they display the distance to Earth’s center?”

“Nope, altitude above sea level, if they’re calibrated right.”

“But the other would work, too, say as a percentage of the average radius?”

“Not really. Earth’s fatter at the Equator than it is at the poles. You’d always have to correct for latitude. And the numbers would be clumsy, always some fraction of a percent of whatever the average is—”

“6371 kilometers.”

“Yeah, that. Try working with fractions of a part per thousand when you’re coming in through a thunderstorm. Give me kilometers or feet above sea level and I’m a lot happier.”

“But say you’re landing in Denver, 1.6 kilometers above sea level.”

“It’s a lot easier to subtract 1.6 from baseline altitude in kilometers than 0.00025 from 1.00something and getting the decimals right. Sea‑level calibrations are a lot easier to work with.”

“So now you know why the book shows zero enthalpy for water at 273K.”

“You’re saying there’s not really zero chemical energy in there, it’s just a convenient place to start counting?”

“That’s exactly what I’m saying. Chemical energy is just another form of potential energy. Zeroes on a potential scale are arbitrary. What’s important is the difference between initial and final states. Altitude’s about gravitational potential relative to the ground; chemists care about chemical potential relative to a specific reaction’s final products. Both concerns are about where you started and where you stop.”

“Gimme a chemical f’rinstance.”

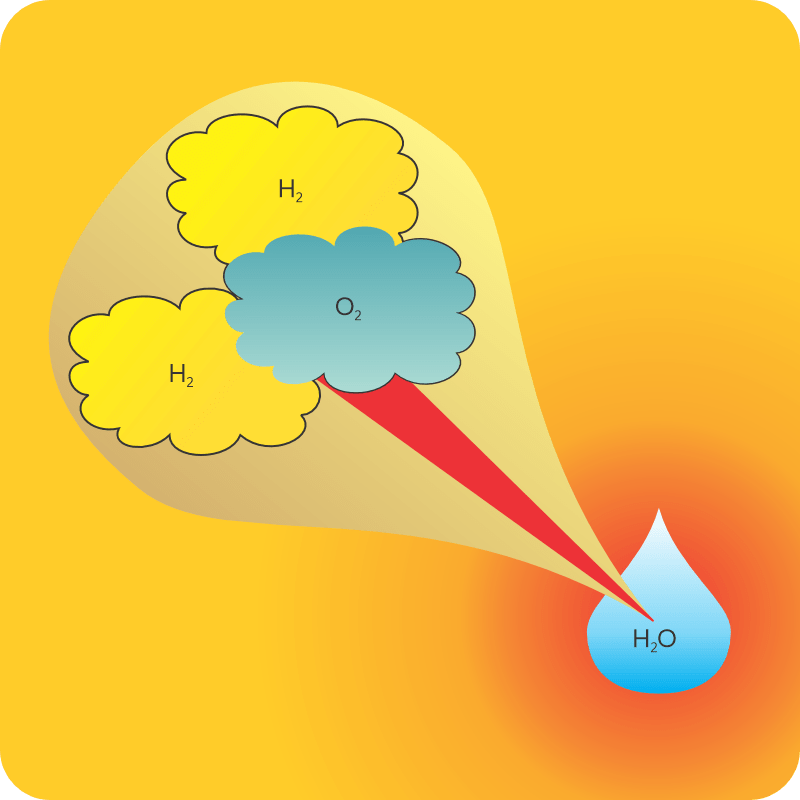

<reading off of Old Reliable> “Reacting 1 gram of oxygen gas and 0.14 gram of hydrogen gas slowly in a catalytic fuel cell at 298K and atmospheric pressure produces one gram of liquid water and releases 18.1 kilojoules of energy. Exploding the same gas mix at the same pressure in a piston also yields 18.1 kilojoules once you cool everything back down to 298K. Different routes, same results.”

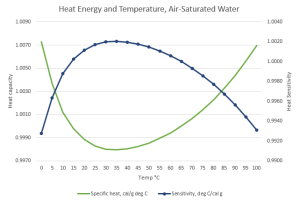

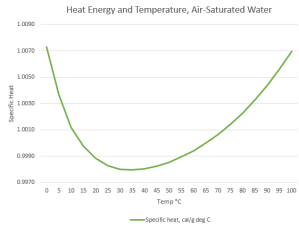

Meanwhile, Jeremy’s wandered over from his gelato stand. “Excuse me, Mr Moire. I read your Crazy Theory about how mammals like to keep their body temperature in the range near water’s minimum Specific Heat, um Heat Capacity, but now I’m confused.”

“What’s the confusion, Jeremy?”

“Well, what you told me before made sense, about increased temperature activates higher‑energy kinds of molecular waggling to absorb the heat. But that means that Heat Capacity always ought to increase with increasing temperature, right?”

“Good thinking. So your problem is…?

“Your graph shows that if water’s cold, warming it decreases its Heat Capacity. Do hotter water molecules waggle less?”

“No, it’s a context thing. Gas and liquid are different contexts. Each molecule in a gas is all by itself, most of the time, so its waggling is determined only by its internal bonding and mass configuration. Put that molecule into a liquid or solid, it’s subject to what its neighbors are doing. Water’s particularly good at intermolecular interactions. You know about the hexagonal structure locked into ice and snowflakes. When water ice melts but it’s still at low temperature, much of the hexagonal structure hangs around in a mushy state. A loose structure’s whole‑body quivering can absorb heat energy without exciting waggles in its constituent molecules. Raising the temperature disrupts that floppy structure. That’s most of the fall on the Heat Capacity curve.”

“Ah, then the Sensitivity decrease on the high‑temperature side has to do with blurry structure bits breaking down to tinier pieces that warm up more from less energy. Thanks, Mr Moire.”

“Don’t mention it.”

~~ Rich Olcott

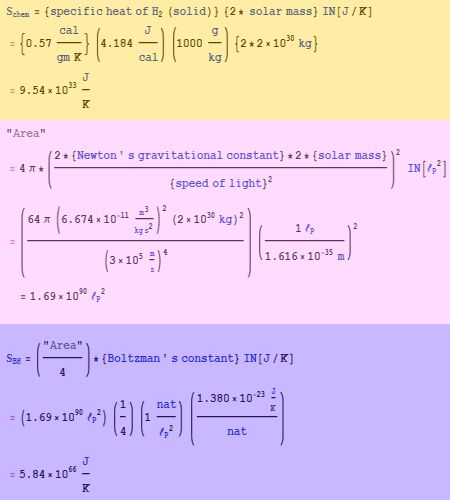

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.”

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.” My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.”

My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.” “Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”