“I ain’t done yet, Sy. I got another reason for Dark Matter being made of faster‑then‑light tachyons.”

“I’m still listening, Vinnie.”

“Dark Matter gotta be electrically neutral, right, otherwise it’d do stuff with light and that doesn’t happen. I say tachyons gotta be neutral.”

“Why so?”

“Stands to reason. Suppose tachyons started off as charged particles. The electric force pushes and pulls on charges hugely stronger than gravity pulls—”

“1036 times stronger at any given distance.”

“Yeah, so right off the bat charged tachyons either pair up real quick or they fly away from the slower‑than‑light bradyon neighborhood leaving only neutral tachyons behind for us bradyon slowpokes to look at.”

“But we’ve got un‑neutral bradyon matter all around us — electrons trapped in Earth’s Van Allen Belt and Jupiter’s radiation belts, for example, and positive and negative plasma ions in the solar wind. Couldn’t your neutral tachyons get ionized?”

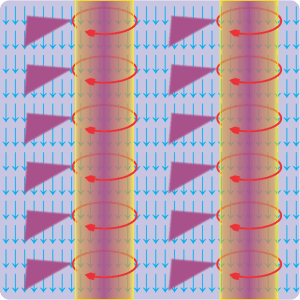

“Probably not much. Remember, tachyon particles whiz past each other too fast to collect into a star and do fusion stuff so there’s nobody to generate tachyonic super‑high‑energy radiation that makes tachyon ions. No ionized winds either. If a neutral tachyon collides with even a high-energy bradyon, the tachyon carries so much kinetic energy that the bradyon takes the damage rather than ionize the tachyon. Dark Matter and neutral tachyons both don’t do electromagnetic stuff so Dark Matter’s made of tachyons.”

“Ingenious, but you missed something way back in your initial assumptions.”

“Which assumption? Show me.”

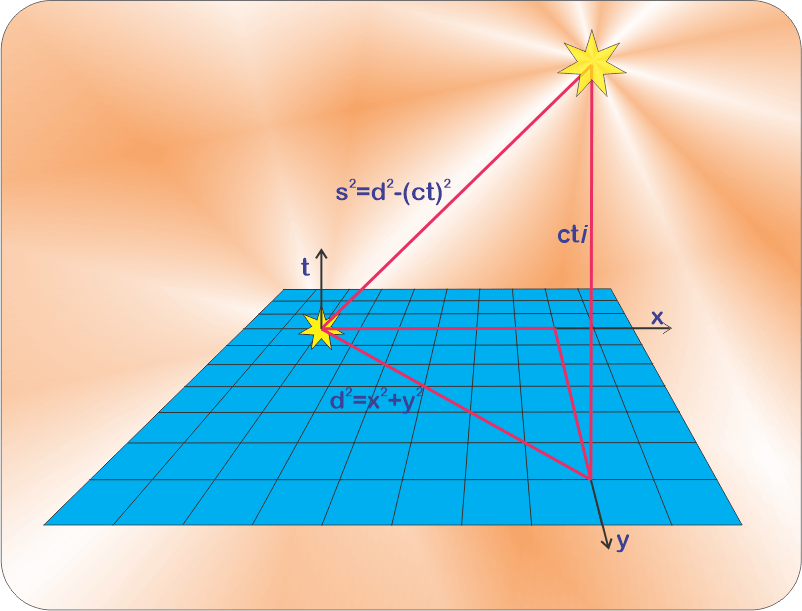

“You assumed that tachyon mass works the same way that bradyon mass does. The math says it doesn’t.” <grabbing scratch paper for scribbling> “Whoa, don’t panic, just two simple equations. The first relates an object’s total energy E to its rest mass m and its momentum p and lightspeed c.”

E² = (mc²)² + (pc)²

“I recognize the mc² part, that’s from Einstein’s Equation, but what’s the second piece and why square everything again?”

“The keyword is rest mass.”

“Geez, it’s frames again?”

“Mm‑hm. The (mc²)² term is about mass‑energy strictly within the object’s own inertial frame where its momentum is zero. Einstein’s famous E=mc² covers that special case. The (pc)² term is about the object’s kinetic energy relative to some other‑frame observer with relative momentum p. When kinetic energy is comparable to rest‑mass energy you’re in relativity territory and can’t just add the two together. The sum‑of‑squares form makes the arithmetic work when two observers compare notes. Can I go on?”

“I’m still waitin’ to hear about tachyons.”

“Almost there. If we start with that equation, expand momentum as mass times velocity and re‑arrange a little, you get this formula

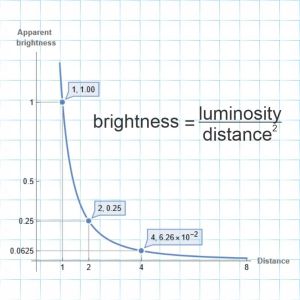

E = mc² / √(1 – v²/c²)

The numerator is rest‑mass energy. The v²/c² measures relative kinetic energy. The Lorentz factor down in the denominator accounts for that. See, when velocity is zero the factor is 1.0 and you’ve got Einstein’s special case.”

“Give me a minute. … Okay. But when the velocity gets up to lightspeed the E number gets weird.”

“Which is why c is the upper threshold for bradyons. As the velocity relative to an observer approaches c, the Lorentz factor approaches zero, the fraction goes to infinity and so does the object’s energy that the observer measures.”

“Okay, here’s where the tachyons come in ’cause their v is bigger than c. … Wait, now the equation’s got the square root of a negative number. You can’t do that! What does that even mean?”

“It’s legal, when you’re careful, but interpretation gets tricky. A tachyon’s Lorentz factor contains √(–1) which makes it an imaginary number. However, we know that the calculated energy has to be a real number. That can only be true if the tachyon’s mass is also an imaginary number, because i/i=1.”

“What makes imaginary energy worse than imaginary mass?”

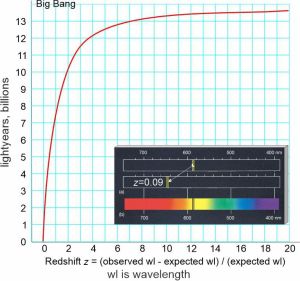

“Because energy’s always conserved. Real energy stays that way. Imaginary mass makes no sense in Newton’s physics but in quantum theory imaginary mass is simply unstable like a pencil balanced on its point. The least little jiggle and the tachyon shatters into real particles with real kinetic energy to burn. Tachyons disintegrating may have powered the Universe’s cosmic inflation right after the Big Bang — but they’re all gone now.”

“Another lovely theory shot down.”

~ Rich Olcott