“It’s like Mark Twain said, Jeremy — ‘History may not repeat itself, but it rhymes.‘ Newton identified gravity as a force; Einstein proposed the Cosmological Constant. Newton worked the data to develop his Law of Gravity; Friedmann worked Einstein’s theory to devise his model of an exponentially expanding Universe. Newton was uncomfortable with gravity’s ability to act at a distance; Einstein called the Cosmological Constant ‘his greatest blunder.’ The parallels go on.”

“Why didn’t Einstein like the Constant if it explains how the Universe is expanding?”

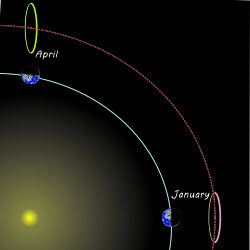

“It wasn’t supposed to. Expanding Universes weren’t in fashion a century ago when Einstein wrote that paper. At the time everyone including Einstein thought we live in a steady state universe. His first cut at a General Relativity field equation implied a contracting universe so he added a constant term to balance out the contraction even though it made the dynamics look unstable — the Constant had to have just the right value for stability. A decade later Hubble’s data pointed to expansion and Friedman’s equations showed how that can happen.”

“I guess Einstein was embarrassed about that, huh, Mr Moire?”

“Well, he’d thought all along that the Constant was mathematically inelegant. Besides, the Constant isn’t just a number or a term in an equation, it’s supposed to represent a real process in operation. Like Newton’s problem with gravity, Einstein couldn’t identify a mechanism to power the Constant.”

“Power it to do what?”

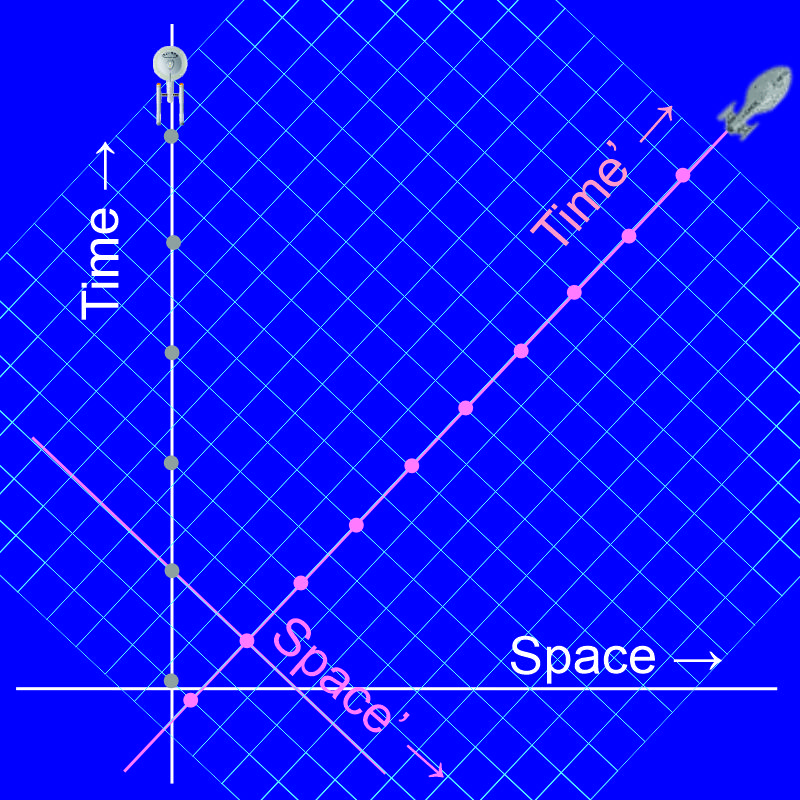

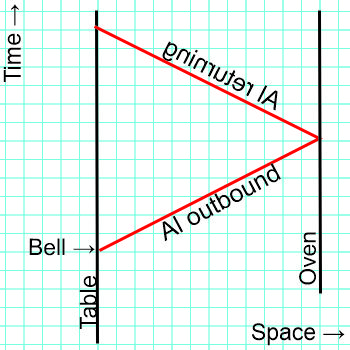

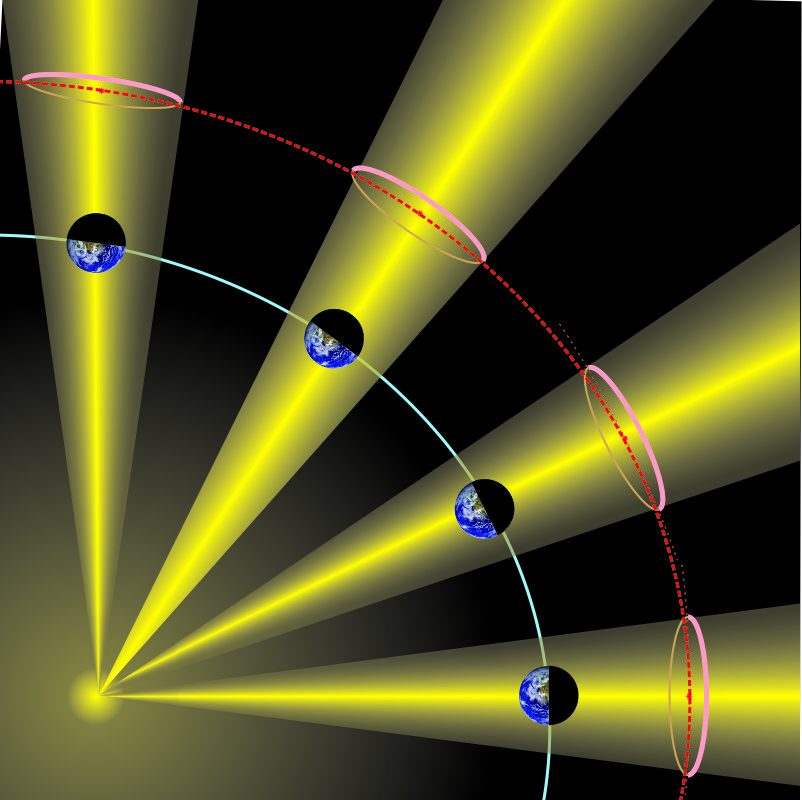

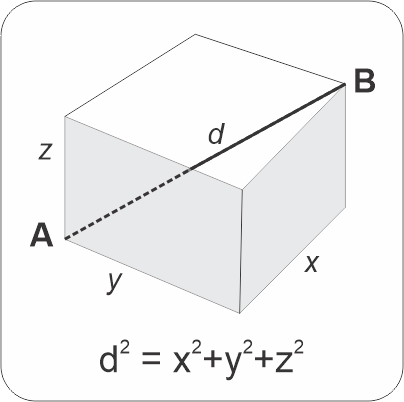

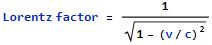

“Think about universal constants, like the speed of light or the electron charge. Doesn’t matter where you are or how fast you’re traveling in which inertial frame, they’ve got the same values. If the Constant is indeed a constant, it contributes equally to cosmological dynamics from every position in space, whether inside a star or millions of lightyears from any galaxy. Every point must exert the same outward force in every direction or there’d be swirling. And it multiplies — every instant of general expansion makes new points in between the old points and they’ll exert the same force, too.”

“That’s what makes it exponential, right?”

“Good insight. It’s a pretty weak force per unit volume, weaker than gravity. We know that because galaxies and galaxy cluster structures maintain integrity even as they’re drifting apart from each other. Even so, a smidgeon of force from each unit volume in space adds up to a lot of force. Multiply force by distance traveled — that’s a huge amount of energy spent against gravity. The big puzzle is, what’s the energy source? Most of the astrophysics community nominates dark energy to power the Cosmological Constant but that’s not much help.”

“As Dr Prather says in class, Mr Moire, ‘You sound tentative. Please expound.‘ Why wouldn’t dark energy be the power source?”

“In Physics we use the word ‘energy‘ with a very specific meaning. Yes, it gets heavy use with sloppy meanings in everything from show business to crystal therapy, but in hard science nearly every serious research program since the 18th Century has entailed quantitative energy accounting. The First Law of Thermodynamics is conservation of energy. Whenever we see something heating up, a chemical reaction running or a force being applied along a distance, physicists automatically think about the energy being expended and where that energy is coming from. Energy’s got to balance out. But the Constant breaks that rule — we have no idea what process provides that energy. Calling the source ‘dark energy‘ just gives it a name without explaining it.”

“Isn’t the missing energy source evidence against Friedmann’s and Einstein’s equations?”

“That’s a tempting option and initially a lot of researchers took it. Unfortunately, it seems that dark energy is a thing. Or maybe a lot of little things. Several different lines of evidence say that the Constant constitutes twice as much mass‑energy as all normal and dark matter combined. Worse yet, as the Universe expands that share will increase.”

“Wait, will the dark energy invade normal matter and break us up?”

“People argue about that. Normal matter’s held together by electromagnetic forces which are 1038 times stronger than gravity, far stronger yet than dark energy. Dark matter’s gravity helps to hold galaxies together, but who knows what holds dark matter together?”

~~ ROlcott