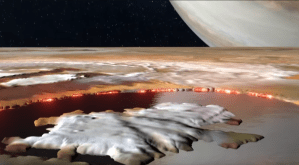

Susan Kim and Kareem are supervising while Cal mounts a new poster in the place of honor behind his cash register. “A little higher on the left, Cal.”

“How’s this, Susan? Hey, Sy, get over here and see this. Ain’t it a beaut?”

“Nice, Cal. What’s it supposed to be? Is that Jupiter in the background?”

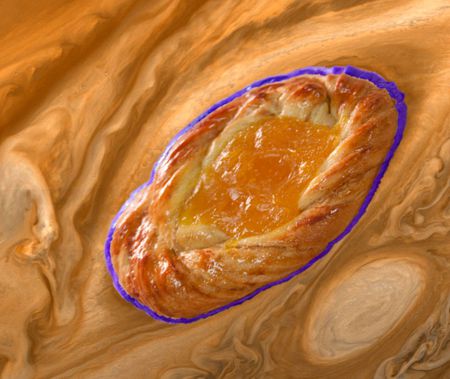

“Yeah, Jupiter all right. Foreground is supposed to be a particular spot on its moon Io. They think it’s a lake of molten sulfur!”

“No way, from that picture at least! I’ve seen molten sulfur. It goes from pale yellow to dark red as you heat it up, but never black like that.”

“It’s not going to be lab-pure sulfur, Susan. This is out there in the wild so it’s going to be loaded with other stuff, especially iron. But the molten sulfur I’ve seen in volcanoes is usually burning with a blue flame. I guess the artist left that out.”

“No oxygen to burn it with, Kareem. Why did you mention iron in particular?”

“Yeah, this article I took the image from says that lake’s at 1400°C. I thought blast furnaces ran hotter than that.”

I’ve been looking things up on Old Reliable. “They do, Cal, typically peaking near 2000°C.”

“So if this lake has iron in it, why isn’t the iron solid?”

“Same answer as I gave to Susan, Cal. The iron’s not pure, either. Mixtures generally melt or freeze at lower temperatures than their pure components. Sy would probably start an entropy lecture—”

“I would.”

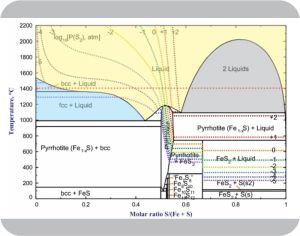

“But I’m a geologist. Earth is about ⅓ iron. That’s mixed in with about 10% as much sulfur, mostly in the core where pressures and temperatures are immense. We want to understand conditions down there so we’ve spent tons of lab time and computer time to determine how various iron‑sulfur mixtures behave at different temperatures and pressures. It’s complicated.” <brings up an image on his phone> “Here’s what we call the system’s phase diagram.”

“You’re going to have to read that to us.”

Click image to expand

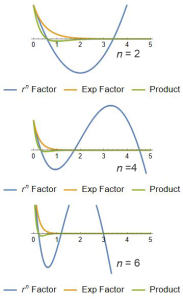

“I expected to. Temperature increases along the y‑axis. Loki’s temp is at the dotted red line. Left‑to‑right we’ve got increasing sulfur:iron ratios — pure iron on the left, pure sulfur on the right. The idea is, pick a temperature and a mix ratio. The phase diagram tells you what form or forms dominate. The yellow area, for instance, is liquid — molten stuff with each kind of atom moving around randomly.”

“What’s the ‘bcc’ and ‘fcc’ about?”

“I was going to get to that. They’re abbreviations for ‘body‑centered cubic’ and ‘face‑centered cubic’, two different crystalline forms of iron. The fcc form dominates below that horizontal line at about 1380°C, converts to bcc above that temperature. Pure bcc freezes at about 1540°C, but add some sulfur to the molten material and you drive that freezing temperature down along the blue‑yellow boundary.”

“And the gray area?”

“Always a fun thing to explain. It’s basically a no‑go zone. Take the point at 1400°C and 80:20 sulfur:iron, for instance. The line running through the gray zone along those red dots, we call it a tie line, skips from 60:40 to 95:5, right? That tells you the 60:40 mix doesn’t accept additional sulfur. The extra part of the 80:20 total squeezes out as a separate 95:5 phase. Sulfur’s less dense than iron so the molten 95:5 will be floating on top of the 60:40. Two liquids but they’re like oil and water. If you want a uniform 80:20 liquid you have to shorten the tie line by raising the temp above 2000°C.”

“All that’s theory. Is there evidence to back it up?”

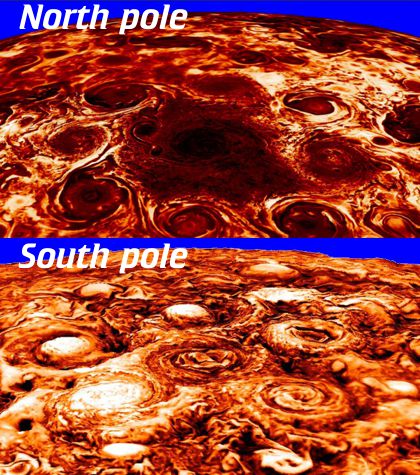

“Indeed, Sy, now that Juno‘s up there taking pictures. When the spacecraft rounded Io last February JunoCam caught several specular reflections of sunlight just like it had bounced off mirrors. At first the researchers suspected volcanic glass but the locations matched Loki and other hot volcanic calderas. The popular science press can say ‘sulfur lakes’ but NASA’s being cagey, saying ‘lava‘ — composition’s probably somewhere between 10:90 and 60:40 but we don’t know.”

a lava lake on Jupiter’s moon Io

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS

~ Rich Olcott

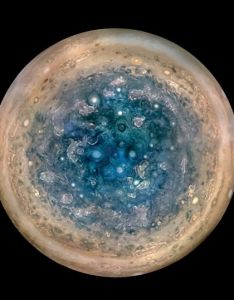

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”