Susan suddenly sits bolt upright. “WOW! Kareem, that Chicxulub meteor that killed off the dinosaurs — paleontologists found iridium from it all over the world, right?”

“Right, the famous K‑T or K‑Pg boundary So?”

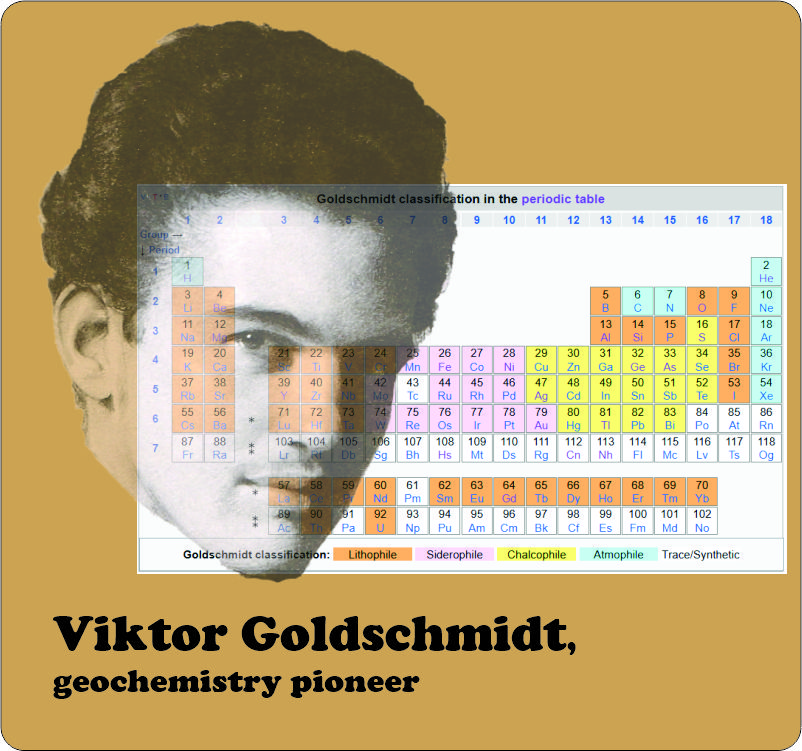

“It’d take a lot of iridium to cover the world. Iridium’s deep in the Periodic Table’s Soft Siderophile territory. Iron’s Soft. When Earth was molten, iron would extract and concentrate iridium. That’s why there’s so little iridium in Earth’s crust ’cause it’s all gone to the core. That iridium‑carrying meteorite must have been the iron kind.”

“Probably.”

Vinnie guffaws. “HAW! Earth’s Hard and crunchy on the outside, Soft and chewy in the inside, just like a good cookie.”

“Or an armored knight, from the dragon’s viewpoint. But how did Earth get that way, Cathleen?”

“Long story, Sy. The academics are still arguing about the details.”

“I love a good story, especially if it ends up explaining asteroid Psyche.”

“It starts 4½ billion years ago, when the Solar System was a rotating disk of galactic debris, clouds of hydrogen plus heavier dust and grit spewed out by energetic stars. Some of the atoms in that grit were important, right, Kareem?”

“Yup. Iron and nickel for planetary cores, silicon and oxygen for the crusts, radioactive isotopes of potassium, uranium and thorium but especially the short‑lived radioactives like aluminum‑26. Half‑life for that one’s only a million years.”

Al, Eddie and Vinnie erupt.

”If the short‑timers are gone, how come you say they were important?”

”How do we know they were even there?”

”If it’s such a short‑timer, is that stuff even a thing any more?”

Kareem’s not used to such a barrage but Cathleen’s a seasoned teacher. “Aluminum‑26 definitely is still a thing, because it’s continually produced by cosmic rays colliding with silicon atoms that aren’t too deeply buried. The production rate is so steady that Kareem’s colleagues estimate how long a meteorite was exposed to cosmic rays from its load of aluminum‑26 decay products compared to its related stable isotopes. We know aluminum‑26 was in the early debris because we’ve found its decay products on Earth. We even know how much — about 50 atoms per million stable aluminum atoms.”

Kareem regains his footing. “As to why it’s important, molten silicate droplets in the early system became chondrules when they aggregated to form chondritic meteorites. The droplets couldn’t have stayed that hot just from nuclear fission by their long‑lived radioactives. The short‑timers, especially aluminum‑26, must have supplied the extra heat early on. If short‑timers could keep the droplets molten, they certainly could have kept the newly‑forming planets molten for a while. Being fluid’s important because that’s the only state where Susan’s Hard‑Soft phase separation can happen.”

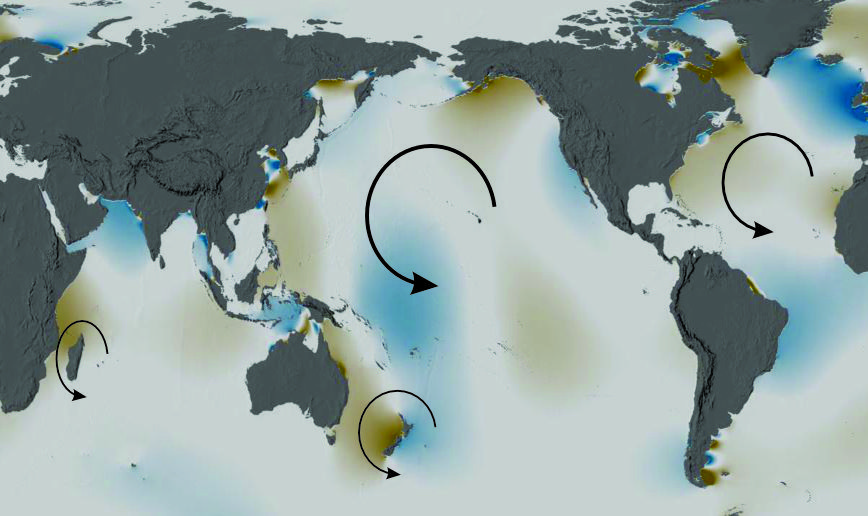

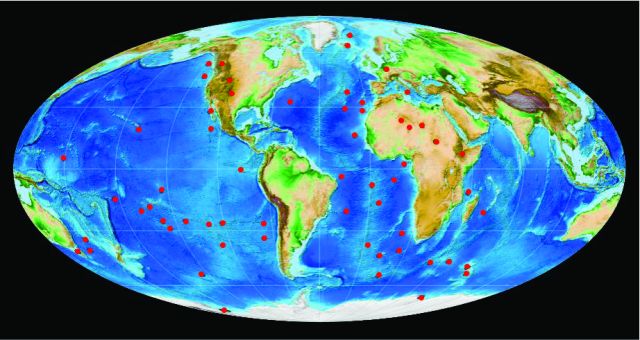

Cathleen nods. “The radioactives were just part of the story, though. The early system was a chaotic place. Forget notions of everything smoothly whirling around like the rings of Saturn. Except for the biggest objects, the idea of an orbit was just silly. Each object was gravitationally influenced by beaucoodles of other objects of all sizes that didn’t even all go in the same direction. There was crashing, lots of crashing. Every smash‑up converted kinetic energy to heat, lots of heat. Each collision could generate fragments which would cascade on to other collisions, maybe even become meteorites. Large objects would accumulate mass and heat energy in violent mergers with smaller objects. A protoplanet’s atom‑level Hard‑Hard and Soft‑Soft interactions would have plenty of chemical opportunities to assemble cohesive masses rising or sinking through the liquid melt just because of buoyancy and there you’ve got your layers.”

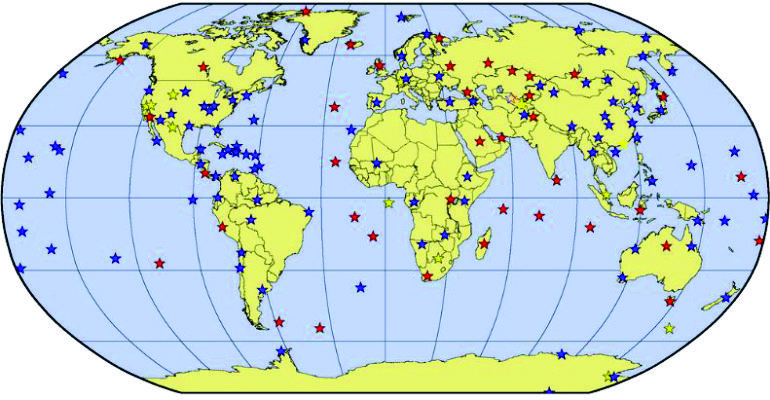

“But collisions didn’t have to be violent, Cathleen. Fragments could hang together through gravity or surface stickiness. That’s how the Bennu and Ryugu rubble pile asteroids formed.”

“Good point, Kareem, and that brings us to Psyche. We know its density is higher than stone but less than iron. The asteroid could be part of a planetoid’s interior, surviving after violent collisions chipped away the surface rock. It could be a rubble pile of loose metallic bits. It could be a mix of metal and rock like the Museum’s pallasite slice. Or an armored shell. We just won’t know until the Psyche mission gets there.”

~~ Rich Olcott