Power’s back on. The elevator lets us out on the second floor where we proceed into Eddie’s Pizza Place. We order, find a table, and Cathleen cocks an eyebrow. “So, Anne, you’re a time‑traveler?”

“Lots of dimensions, actually. Time, space, probability… Once I accidentally jumped into a Universe where the speed of light was a lot slower. I was floating near a planet in a small system whose sun flared up but it took a long, long time for the flash to reflect off the planet behind me. Funny, I felt stiffer than usual. It was a lot harder to move my arms. I avoid cruising dimensions like that one.”

<The other eyebrow goes up> “Wait, what’s the speed of light got to do with dimensions? And why would it affect moving your arms?”

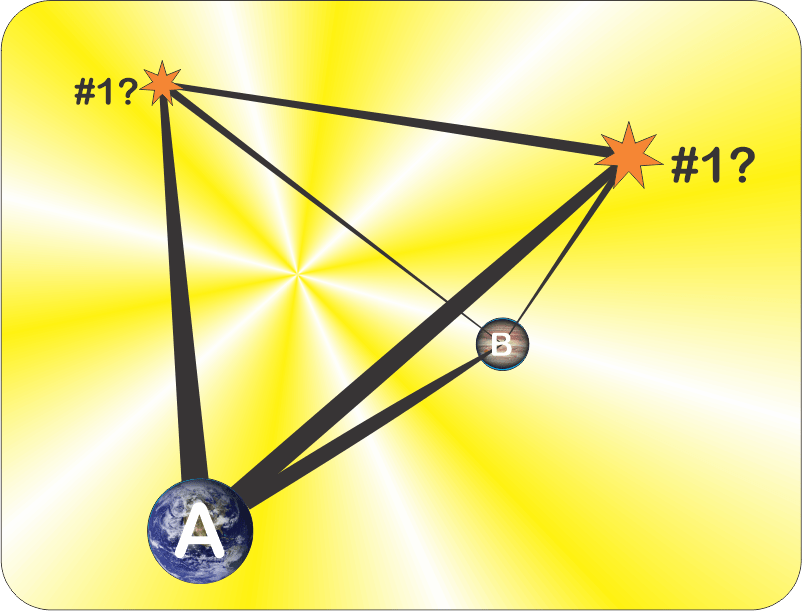

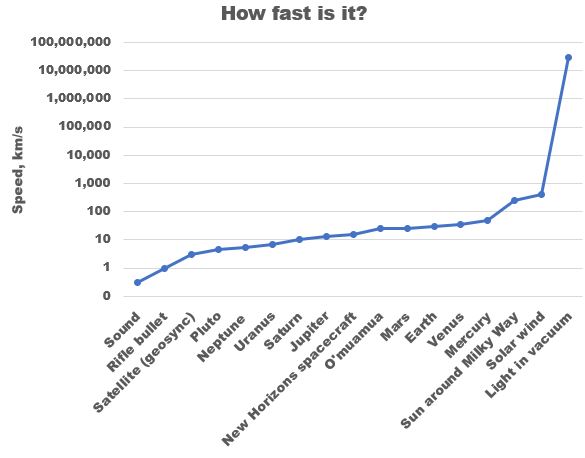

My cue. “Physics has a long‑standing problem with the speed of light and a dozen or so other fundamental numbers like Newton’s gravitational constant and Einstein’s cosmological constant. We can measure them but we can’t explain why they have the values they do. Okay, the speed of light depends on electric and magnetic force constants, but we can’t explain those, either — the rabbit hole just gets deeper. In practice, our Laws of Physics are a set of equations with blanks for plugging in the measured values. People have suggested that there’s a plethora of alternate universes with the same laws of physics we have but whose fundamental constants can vary from ours. Apparently Anne traveled along a dimension that connects universes with differing values of lightspeed.”

“I suppose. … But the arm‑moving part?”

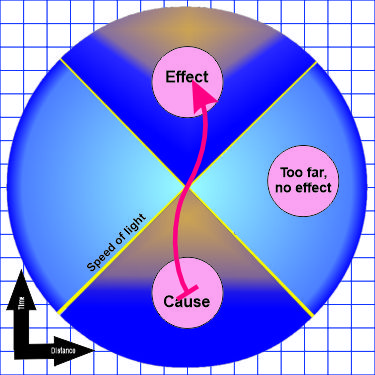

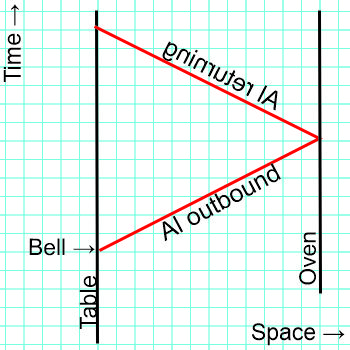

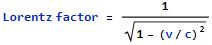

“An effect of Special Relativity. Newton’s Second Law a=F/m says that an object’s acceleration equals the applied force per unit mass. That works fine in every‑day life but not when the object’s velocity gets close to lightspeed.” <jotting on a paper napkin> “I don’t see Vinnie nearby so here’s the relativistic equation: a=(F/m)×√[1–(v/c)²]. The v/c ratio compares object velocity to lightspeed. The Lorentz factor, that square root, is less than 1.0 for velocities less than lightspeed. This formula says a given amount of force per unit mass produces less acceleration than Newton would expect. How much less depends on how fast you’re already going. In fact, the acceleration boost approaches zero when v approaches c. With me?”

“If your factor’s exactly zero, then even an infinite force couldn’t accelerate you, right? But what’s all that got to do with my arm?”

“Zero acceleration, mm‑hm. Suppose your arm’s rest mass and muscle force per unit mass are the same in the slow‑light universe as they are in ours. The Lorentz factor’s different. Lightspeed in our Universe is 3×108 m/s. Suppose you wave your arm at 10 m/s. Your Lorentz factor here is √[1–(10/3×108)²] which is so close to unity we couldn’t measure the difference. Now suppose ‘over there’ the lightspeed is 20 m/s and you try the same wave. The Lorentz formula works out to √[1–(10/20)²] or about 85%. That wave would cost you about 15% more effort.”

<Both eyebrows down> “Have you tried going forward in time?”

“Sure, but I can’t get very far. It’s like I’ve got an anchor ‘here.’ I can move back ‘here’ from the past, no problem, but when I try to move forward from ‘here’ even a day or so … It’s hard to describe but as I go everything feels fuzzier and then I get queasy and have to stop. Do you have an explanation for that, Sy?”

“Well, an explanation but I can’t tell you it’s correct. Einstein thought it conflicts with Relativity, other people disagree. According to the growing block theory of time, the past and present are set and unchanging but the future doesn’t exist until we get there. Your description sounds like a build on that theory, like maybe the big structures extend a bit beyond us but their quantum details are still chaotic until time catches up with them. There are a few reports of lab experiments that would be consistent with something like that but it’s early days in the research.”

“As the saying goes, ‘Time will tell,’ right, Sy?”

“Mm-hm, lo que será, será.“

~ Rich Olcott