“Amanda! Amanda! Amanda!”

“All right, everyone, settle down for our final Crazy Theorist. Jim, you’re up.”

“Thanks, Cathleen. To be honest I’m a little uncomfortable because what I’ve prepared looks like a follow-on to Newt’s idea but we didn’t plan it that way. This is about something I’ve been puzzling over. Like Newt said, black holes have mass, which is what everyone pays attention to, and charge, which is mostly unimportant, and spin. Spin’s what I’ve been pondering. We’ve all got this picture of a perfect black sphere, so how do we know it’s spinning?”

Voice from the back of the room — “Maybe it’s got lumps or something on it.”

“Nope. The No-hair Theorem says the event horizon is mathematically smooth, no distinguishing marks or tattoos. Question, Jeremy?”

“Yessir. Suppose an asteroid or something falls in. Time dilation makes it look like it’s going slower and slower as it gets close to the event horizon, right? Wouldn’t the stuck asteroid be a marker to track the black hole’s rotation?”

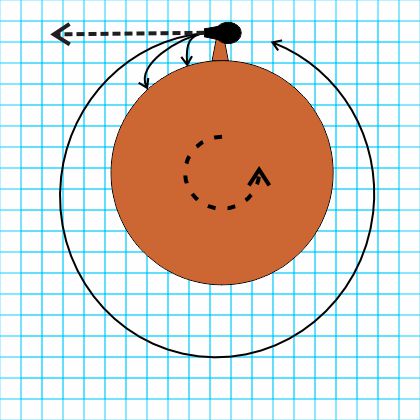

“Excellent question.” <Several of Jeremy’s groupies go, “Oooh.”> “Two things to pay attention to here. First, if we can see the asteroid, it’s not yet inside the horizon so it wouldn’t be a direct marker. Beyond that, the hole’s rotation drags nearby spacetime around with it in the ergosphere, that pumpkin‑shaped region surrounding the event horizon except at the rotational poles. As soon as the asteroid penetrates the ergosphere it gets dragged along. From our perspective the asteroid spirals in instead of dropping straight. What with time dilation, if the hole’s spinning fast enough we could even see multiple images of the same asteroid at different levels approaching the horizon.”

Jeremy and all his groupies go, “Oooh.”

“Anyhow, astronomical observation has given us lots of evidence that black holes do spin. I’ve been pondering what’s spinning in there. Most people seem to think that once an object crosses the event horizon it becomes quantum mush. There’d be this great mass of mush spinning like a ball. In fact, that was Schwarzchild’s model for his non-rotating black hole — a simple sphere of incompressible fluid that has the same density throughout, even at the central singularity.”

VBOR — “Boring!”

“Well yeah, but it might be correct, especially if spaghettification and the Firewall act to grind everything down to subatomic particles on the way in. But I got a different idea when I started thinking about what happened to those two black holes that LIGO heard collide in 2015. It just didn’t seem reasonable that both of those objects, each dozens of solar masses in size, would get mushed in the few seconds it took to collide. Question, Vinnie?”

“Yeah, nice talk so far. Hey, Sy and me, we talked a while ago about you can’t have a black hole inside another black hole, right, Sy?”

“That’s not quite what I said, Vinnie. What I proved was that after two black holes collide they can’t both still be black holes inside the big one. That’s different and I don’t think that’s where Jim’s going with this.”

“Right, Mr Moire. I’m not claiming that our two colliders retain their black hole identities. My crazy theory is that each one persists as a high‑density nubbin in an ocean of mush and the nubbins continue to orbit in there as gravity propels them towards the singularity.”

VBOR —”Orbit? Like they just keep that dance going after the collision?”

“Sure. What we can see of their collision is an interaction between the two event horizons and all the external structures. From the outside, we’d see a large part of each object’s mass eternally inbound, locked into the time dilation just above the joined horizon. From the infalling mass perspective, though, the nubbins are still far apart. They collide farther in and farther into the future. The event horizon collision is in their past, and each nubbin still has a lot of angular momentum to stir into the mush. Spin is stirred-up mush.”

Cathleen’s back at the mic. “Well, there you have it. Amanda’s male-pattern baldness theory, Newt’s hyper‑planetary gear, Kareem’s purple snowball or Jim’s mush. Who wins the Ceremonial Broom?”

The claque responds — “Amanda! Amanda! Amanda!”

~ Rich Olcott