“C’mon, Vinnie, you’re definitely doing Sy stuff. I ask you a question about how come rockets can get to the Moon easier than partway and you go round the barn with ballistics and cruisers. Stop dodging.”

“Now, Al, Vinnie’s just giving you background, right. Vinnie?”

“Right, Sy, though I gotta admit a lot of our talks have gone that way. So what’s your answer?”

“Nice try, Vinnie. You’re doing fine, so keep at it.”

“Okay. <deep breath> It has to do with vectors, Al, combination of amount and direction, like if you’re going 3 miles north that’s a vector. You good with that?”

“If you say so.”

“I do. Then you can combine vectors, like if you’re going 3 miles north and at the same time 4 miles east you’ve gone 5 miles northeast.”

“That’s a 3-4-5 right triangle, even I know that one. But that 5 miles northeast is a vector, too, right?”

“You got the idea. Now think about fueling a rocket going up to meet the ISS.”

“Sy said it’s 250 miles up, so we need enough fuel to punch that far against Earth’s gravity.”

“Not even close. If the rocket just went straight up, it’d come straight down again. You need some sideways momentum, enough so when you fall you miss the Earth.”

“Miss the Earth? Get outta here!”

“No, really. Hey, Sy, you tell him.”

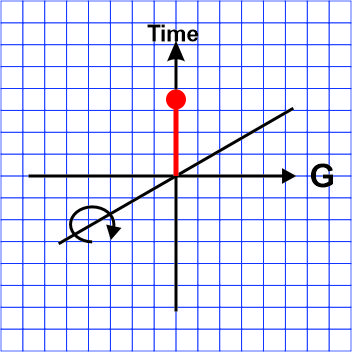

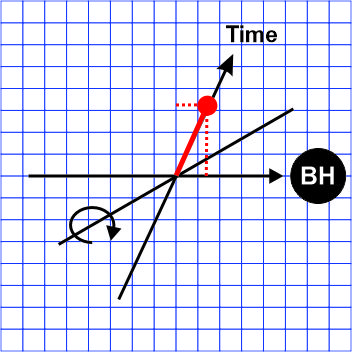

“Vinnie’s right, Al. That insight goes back to Newton. He proposed a thought experiment about building a powerful cannon to fire horizontally from a very tall mountain. <sketching on paper napkin> A ball shot with a normal load of powder might hit the adjacent valley. Shoot with more and more powder, balls would fly farther and farther before hitting the Earth. Eventually you fire with a charge so powerful the ball flies far enough that its fall continues all around the planet. Unless the cannon blows up or the ball shatters.”

“That’s my point, Al. See, Newton’s cannon balls started out going flat, not up. To get up and into orbit you need up and sideways velocity, like on the diagonal. You gotta calculate fuel to do both at the same time.”

“So what’s that got to do with easier to get to the Moon than into orbit?”

“‘S got everything to do with that. Not easier, though, just if you aim right the vectors make it simpler and cheaper to carry cargo to the Moon than into Earth orbit.”

“So you just head straight for the Moon without going into orbit!”

“Not quite that simple, but you got the general idea. Remember when I brought that kid’s top in here and me and Sy talked about centrifugal force?”

“Do I? And I made you clean up all those spit-wads.”

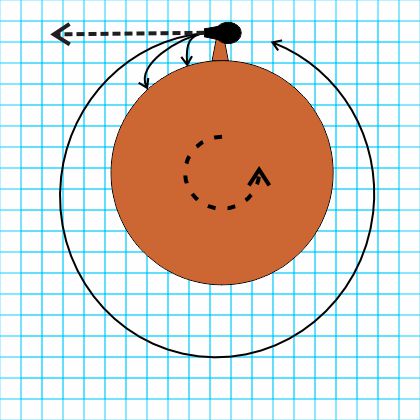

“Yeah, well, suppose that cannon’s at the Equator <adding dotted lines to Sy’s diagram> and aimed with the Earth’s spin and suppose we load in enough powder for the ball to go straight horizontal, which is what it’d do with just centrifugal force.”

“If I’m standing by the cannon it’d look like the ball’s going sideways.”

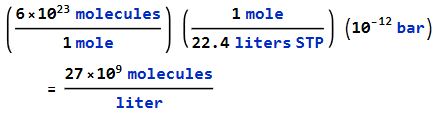

“Yup. Basically, you get the up‑ness for free. We’re not talking about escape velocity here, that’s different. We’re talking about the start of a Hohmann orbit.”

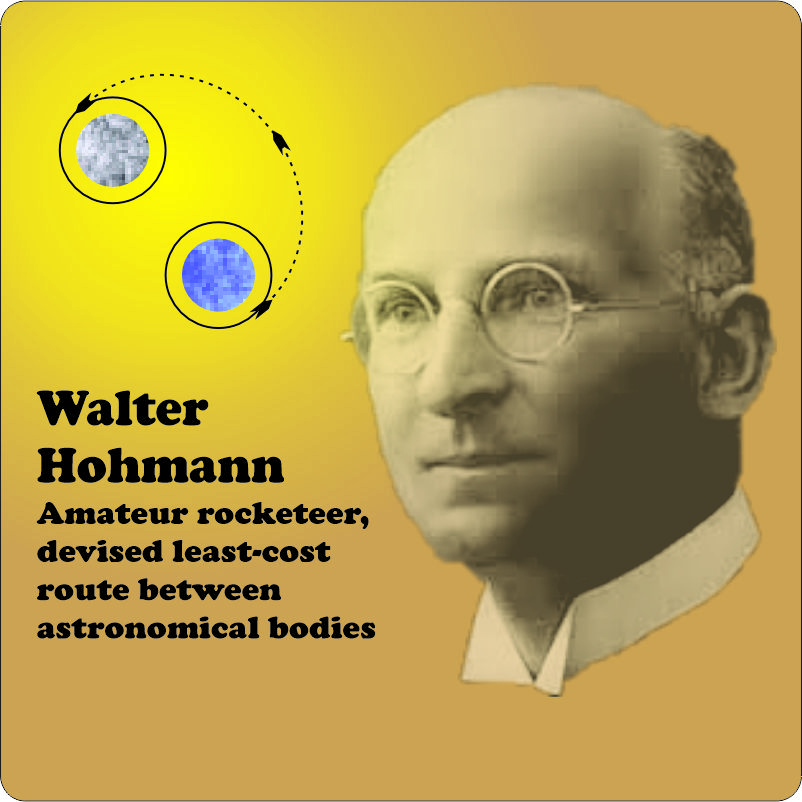

“Who’s Hohmann?”

“German engineer. When he was a kid he read sci‑fi like the rest of us and that got him into the amateur rocketry scene. Got to be a leader in the German amateur rocket club, published a couple of leading‑edge rocket science books in the 1920s but dropped out of the field when the Nazis started rolling and he figured they’d build rocket weapons. Anyhow, he invented this orbit that starts off tangent to a circle around one planet or something, follows an ellipse to end tangent to a circle around something else. Smooth transitions at both ends, cheapest way you can get from here to there. Kinks in the routing cost you fuel and cargo capacity to turn. Guy shoulda patented it.”

“Wait, an orbit’s a mathematical abstraction, not a thing.”

“Patent Office says it’s a business method, Sy. Check out PAS-22, for example.”

“Incredible.”

~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Ken, who asked another question.