“No, Moire, when I said the glasses get dark or light depending I was talking about those glasses that just block out shiny, like from windows across the street when the Sun hits ’em just wrong.”

“I got this, Sy. That’s about polarized light, Feder, and polarized sunglasses. Sy and me, we talked about that when we were thinkin’ Star Trek weapons.”

“You guys talk about everything, Vinnie.”

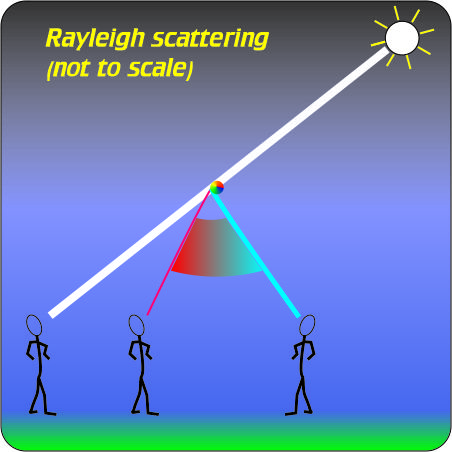

“Pretty much. Anyhow, it goes back to how electrons make light. Electrons got charge and that makes an electric field around them, right? When you jiggle an electron up and down the field jiggles and sooner or later that’ll make some other electron jiggle like maybe in your eye and you see that as light. How’m I doing, Sy?”

“You’re on a roll. Keep it going.”

“Okay, so the electron doesn’t have to jiggle only up and down, it can do side‑to‑side if it feels like it or anything in between and the field goes along with all of that. When you got a lot of electrons doing that together, different‑angle waves go out and that poor second electron gets shoved all around the compass, right?”

“Hey, don’t all those jiggles just cancel each other out?”

“Nah, ’cause their timing’s off. They’re not in sync or nothing so the jiggles push in every direction random‑like.”

“How about lasers? I thought their waves all marched in sync.”

“They’re in sync strong‑and‑weak, but I guess whether they’re up‑and‑down in sync depends on the technology, right, Sy?”

“Right, Vinnie. Simple diode laser beams usually aren’t polarized, but special-purpose lasers may be designed with polarization in the package. Of course, any beam can be polarized if it’s bounced off something at just the right angle.”

“What’s the angle got to do with it, Moire?”

“I bet I know. Sy. Is that bounce angle connected to the prism stuff?”

“Nice shot, Vinnie. Carry on.”

“Ok, Feder, follow me ’cause this is a little complicated. Sy, can I borrow your whiteboard?”

“Sure.”

“Thanks. All right, this thick green wiggle is a regular light ray’s electric field, coming in at a low angle and jiggling in all directions. It hits a window or something, that’s the black line, and some of it gets reflected, that’s the red wiggle, and some gets through but not as much which is why the second green line is skinny. The fast‑slow marks are about wave speeds but it’s why the skinny wiggle runs at that weird angle. We good?”

“Mostly, I guess, but where does the polarization come in?”

“I’m gettin’ there. That’s what the dots are about. I’m gonna pretend that all those different polarization directions boil down to either up‑and‑down, that’s the wiggles, and side to side, that’s the dots. Think of the dots as wiggle coming out and going back in cross‑ways to the up‑and‑down. It’s OK to do that, right, Sy?”

“Done in the best families, Vinnie. Charge on.”

“So anyway, the up‑and‑down field can sink into the window glass and mess around with the atoms in there. They pass some of the energy down through the glass but the rest of it gets gets thrown back out like I show it.”

“But there’s no dots going down.”

“Ah-HAH! The side‑to‑side field doesn’t sink into the glass at all ’cause the atoms ain’t set up right for that. That side‑to‑side energy bounces back out and hits you in the eyes which is why you use those polarizing sunglasses.”

“But how do those glasses work is what I asked to begin with.”

“That’s all I got, Sy, your turn.”

“Nice job, Vinnie. How they cut the glare, Mr Feder, is by blocking only Vinnie’s side‑to‑side waves. Glare is mostly polarized light reflected off of horizontal surfaces like water and roadway. Block that and you’re happy. How they work is by selective absorption. The lenses are made of long, skinny molecules stretched out in parallel and doped with iodine molecules. Iodine’s a big, mushy atom with lots of loosely-held electrons, able to absorb many frequencies but only some polarizations. If a light wave passes by jiggling in the wrong direction, its energy gets slurped. No more glare.”

~~ Rich Olcott