Al’s stacking chairs on tables, trying to close his coffee shop, but Mr Richard Feder (of Fort Lee, NJ) doesn’t let up on Jim. “What’s all this about Gale Crater or Mount Sharp that Curiosity‘s running around? Is it a crater or a mountain? How about it’s a volcano? How do you even tell the difference?”

That’s a lot of questions but Jim’s got game. “Gale is an impact crater, about three and a half billion years old. The impacting meteorite must have hit hard, because Mount Sharp’s in the middle of Gale.”

by Davide Restivo, Aarau, Switzerland

[CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

“Have you ever watched a rain drop hit a puddle? It forces the puddle water downward and then the water springs back up again to form a peak. The same general process happens when a meteorite hits a rocky surface except the solid peak doesn’t flatten out like water does. We know that’s the way many meteor craters on the Moon and here on Earth were formed. We’re pretty sure it’s what happened at Gale — the core of Mount Sharp (formal astronomers call it Aeolis Mons) is probably that kind of peak.”

“Only the core? What about the rest of it?”

“That’s what Curiosity has been digging into.” <I have to smile — Jim’s not one to do puns on purpose.> “The rover’s found evidence that the core’s wrapped up in lots of sedimentary clays, sulfates, hematites and other water-derived minerals of a sort that wouldn’t be there unless Gale had once been a lake like Oregon’s Crater Lake. That in turn says that Mars once had liquid water on its surface. That’s why everyone got so excited when those results came in.”

“Oregon’s Crater Lake was from a meteorite?”

“Oops, bad example. No, that one’s a water-filled volcanic caldera.”

“How do you know? Any chance its volcano will blow?”

“The best evidence, of course, is the mineralogy. Volcanoes are made of igneous rocks — lava, tefra and everything in between. Impact craters are made of whatever was there when the meteorite hit, although the heat and the pressure spike transform a lot of it into some metamorphic form.”

“But you can’t check for that on Mars or the Moon.”

“Mostly not, you’re right, so we have to depend on other clues. Most volcanoes, for instance, are above the local landscape; most impact structures are below-level. There are other subtler tests, like the pattern and distance that ejecta were thrown away from the event. In general we can be 95-plus percent sure whether we’re looking at a volcano or an impact crater. And no, it won’t any time soon.”

“What won’t do what?”

“You asked whether Crater Lake’s volcano will erupt. Mount Mazama blew up 7700 years ago and it’s essentially been dormant ever since.”

“There’s some weasel-wording back there — most volcanoes do this, most impacts do that. What about the exceptions?”

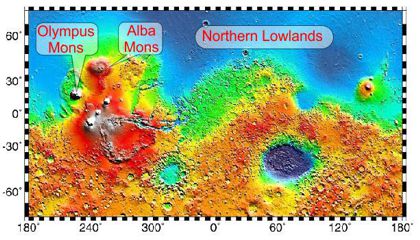

“Those generally have to do with size. The really enormous features are often hard to even recognize, much less classify. On Mars, for instance the Northern Lowlands region is significantly smoother than most of the rest of the planet. Some people think that’s because it’s a huge lava flow that obliterated older impact structures. Other people think the Lowlands is old sea bottom, smooth because meteorites would have splashed water instead of raising rocky craters.”

“I’ll bet ocean.”

“There’s more. You’ve heard about Olympus Mons on Mars being the Solar System’s biggest volcano, but that’s really only by height. Alba Mons lies northeast of Olympus and is far huger by volume — 600 million cubic miles of rock but it’s only 4 miles high. Average slope is half a degree — you’d never notice the upward grade if you walked it. Astronomers thought Alba was just a humungous plain until they got detailed height data from satellite measurements.”

“The other one’s more than 4 miles high?”

“Oh, yeah. Olympus Mons rises about 13.5 miles from the base of its surrounding cliffs. That’s more than the jump from the bottom of the Mariana Trench to the top of Mount Everest.”

“Things on Mars are big, alright.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

Those two electrons push their dust grains apart almost a quintillion times more strongly than gravity pulls them together. And the distance makes no difference — close together or far apart, push wins. You can’t use gravity to build a planet from charged particles.”

Those two electrons push their dust grains apart almost a quintillion times more strongly than gravity pulls them together. And the distance makes no difference — close together or far apart, push wins. You can’t use gravity to build a planet from charged particles.” “Good question. If protons were more positive than electrons, electrostatic repulsion would always be proportional to mass. We couldn’t separate that force from gravity. Physicists have separately measured electron and proton charge. They’re equal (except for sign) to 10 decimal places. Unfortunately, we’d need another 25 digits of accuracy before we could test your hypothesis.”

“Good question. If protons were more positive than electrons, electrostatic repulsion would always be proportional to mass. We couldn’t separate that force from gravity. Physicists have separately measured electron and proton charge. They’re equal (except for sign) to 10 decimal places. Unfortunately, we’d need another 25 digits of accuracy before we could test your hypothesis.”

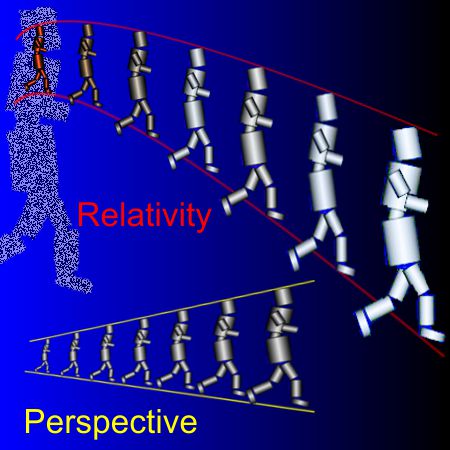

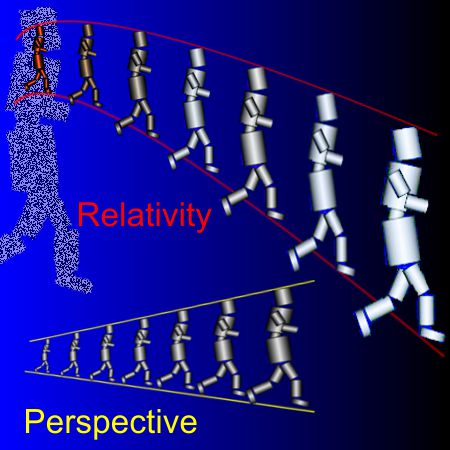

“But GR’s not the only player. Special Relativity’s in there, too.”

“But GR’s not the only player. Special Relativity’s in there, too.”