Vinnie gives me the eye. “That crazy theory of yours is SO bogus, Sy, and there’s a coupla things you said we ain’t heard before.”

“What’s wrong with my Mach’s Principle of Time?”

“If the rest of the Universe is squirting one thing forward along Time, then everything’s squirting everything forward. No push‑back in the other direction. You might as well say that everything’s running away from the Big Bang.”

“That’s probably a better explanation. What are the couple of things?”

“One of them was, ‘geodesic,‘ as in ‘motion along a geodesic.‘ What’s a geodesic?”

“The shortest path between two points.”

“That’s a straight line, Mr Moire. First day in Geometry class.”

“True in Euclid’s era, Jeremy, but things have moved on since then. These days the phrase ‘shortest path’ defines ‘straight line’ rather than the other way around. Furthermore, the choice depends on how you define ‘shortest’. In Minkowski’s spacetime, for instance, do you mean ‘least distance’ or ‘least interval’?”

“How are those different?”

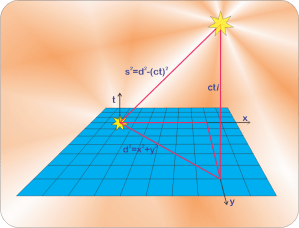

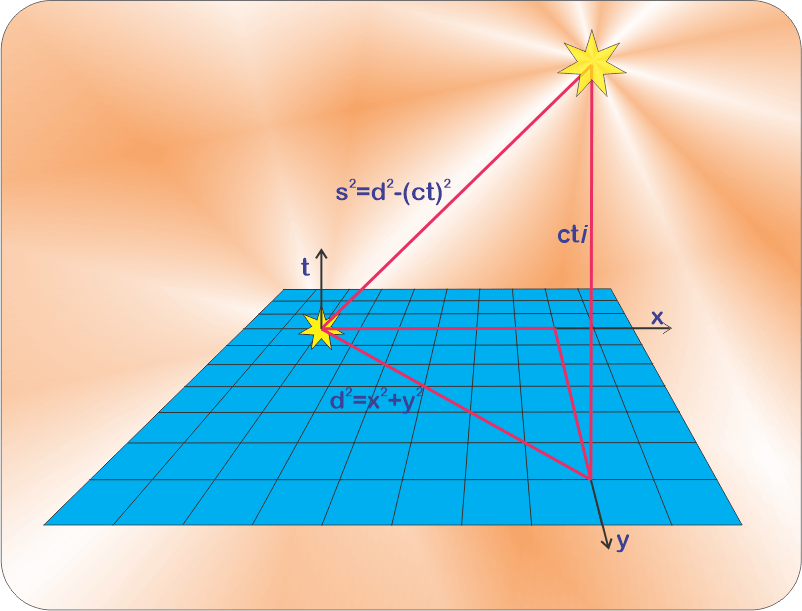

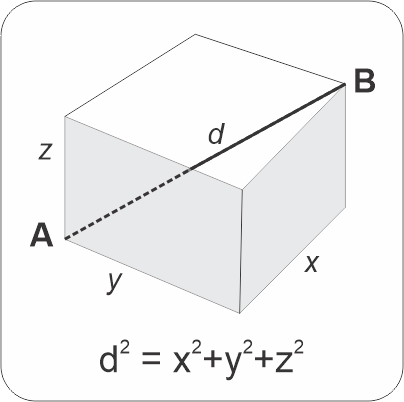

“The word ‘distance’ is a space‑only measurement. Minkowski plotted space in x,y,z terms just like Newton would have if he could’ve brought himself to use René Descartes’ cartesian coordinates. You know Euclid’s a²+b²=c² so you should have no problem calculating 3D distance as d=√(x²+y²+z²).”

“That makes sense. So what’s ‘interval’ about then?”

“Time has entered the picture. In Minkowski’s framework you handle two ‘events’ that may be at different locations and different times by using what he called the ‘interval,’ s. It measures the path between events as

s=√[(x²+y²+z²)–(ct)²]. Usually we avoid the square root sign and work with s².”

“That minus sign looks weird. Where’d it come from?”

“When Minkowski was designing his spacetime, he needed a time scale that could be combined with the x,y,z lengths but was perpendicular to each of them. Multiplying time by lightspeed c gave a length, but it wasn’t perpendicular. He could get that if he multiplied by i=√(–1) to get cti as a partner for x,y,z. Fortunately, that forced the minus sign into the sum‑of‑squares

(x²+y²+z²)–(ct)² formula.”

Vinnie’s getting impatient. “What is an actual geodesic, who cares about them, and what do these equations have to do with anything?”

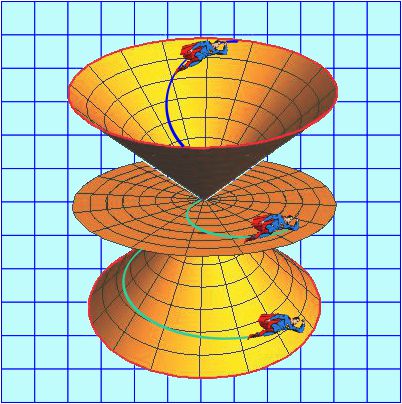

“A geodesic is a path in spacetime. Light always travels along a geodesic. The modern version of Newton’s First Law says that any object not subject to an outside force travels along a geodesic. By definition the geodesic is the shortest path, but you can’t select which path from A to B is the shortest unless you can measure or calculate them. There’s math to tell us how to do that. Time’s a given in a Newtonian Universe, not a coordinate, so geodesics are distance‑only. We calculate d along paths that Euclid would recognize as straight lines. That’s why the First Law is usually stated in terms of straight lines.”

“So the lines can go all curvy?”

“Depends, Vinnie. When you’re piloting an over‑water flight, you fly a steady bearing, right?”

“Whenever ATC and the weather lets me. It’s the shortest route.”

“So according to your instruments you’re flying a straight line. But if someone were tracking you from the ISS they’d say you’re flying along a Great Circle, the intersection of Earth’s surface with some planar surface. You prefer Great Circles because they’re shortest‑distance routes. That makes them geodesics for travel on a planetary surface. Each Circle’s a curve when viewed from off the surface.”

“Back to that minus sign, Mr Moire. Why was it fortunate?”

“It’s at the heart of Relativity Theory. The expression links space and time in opposite senses. It’s why space compression always comes along with time dilation.”

“Oh, like at an Event Horizon. Wait, can’t that s²=(x²+y²+z²)–(ct)² arithmetic come out zero or even negative? What would those even mean?”

“The theory covers all three possibilities. If the sum is zero, then the distance between the two events exactly matches the time it would take light to travel between them. If the sum is positive the way I’ve written it then we say the geodesic is ‘spacelike’ because the distance exceeds light’s travel time. If it’s negative we’ve got a ‘timelike’ geodesic; A could signal B with time to spare.”

~ Rich Olcott

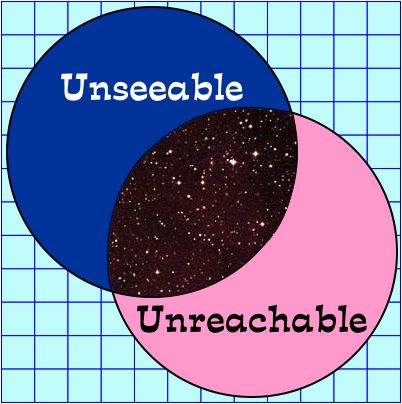

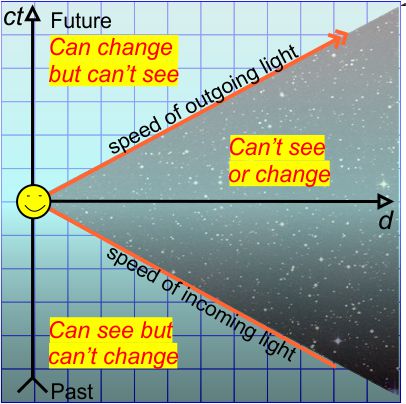

The rest of the Minkowski diagram could do for a Venn diagram. We at (0,0,0,0) can do something that will cause something to happen at (ct,x,y,z) to the left of the top orange line. However, we won’t be able to see that effect until we time-travel forward to its t. That region is “reachable but not seeable.”

The rest of the Minkowski diagram could do for a Venn diagram. We at (0,0,0,0) can do something that will cause something to happen at (ct,x,y,z) to the left of the top orange line. However, we won’t be able to see that effect until we time-travel forward to its t. That region is “reachable but not seeable.”

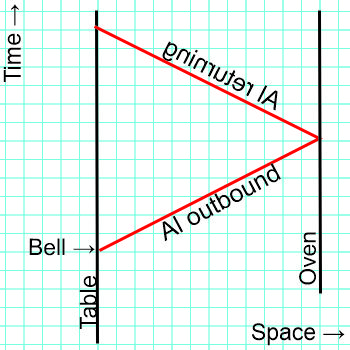

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.