I needed some time to mull over what Cathleen had told me about Tabby’s Star, so I went to the counter to replenish our coffee and scones. When I returned I said, “OK, let’s recap. Dr Boyajian’s Planet Hunters citizen scientists found a star that dims oddly. But I understand there’s lots of variable stars out there. What’s so special about this one that the SETI project got interested?”

“There’s variable stars and variable stars, but this one shouldn’t vary. Look, one of the triumphs of 20th-century science is that we pretty much understand how stars work. You tell me a handful of a star’s properties, things like radius, surface temperature, iron/hydrogen ratio, a couple more, and I can give you its whole life story from light-up to nova. We’ve catalogued about 70,000 variable stars. Virtually all of them do episodic brightening — pulsating or flaring up. There’s about a hundred that dim more or less regularly, but they’re supergiants with cool, sooty atmospheres. Tabby’s Star is a flat-out normal F-type main sequence star, about 1½ times the Sun’s mass and a little bit warmer. Like the clean-cut kid next door — no reason to expect trouble from it.”

“So if it’s not the star itself that’s dimming, then something must be getting between it and us.”

“Well, yeah. The question is what. There’s so many theories that one pair of authors wrote a 15-page paper just classifying and rating them.”

“Gimme a few.”

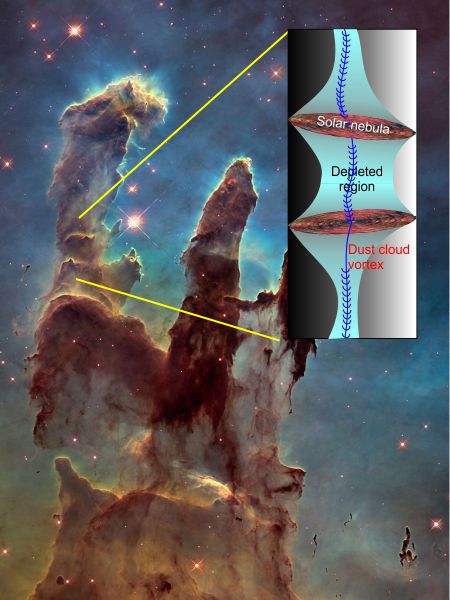

“Clouds of interstellar dust, for starters. Sodium’s sparse in stars and the interstellar medium, but it’s got two easily recognized strong absorption lines in the yellow part of the visible spectrum. Tabby’s sodium lines are broad and weak like you’d expect in a star’s atmosphere, but in the data they’re overlain by sharp, intense absorption peaks that can only come from sodium-bearing gas or dust in the nine-quadrillion-mile journey from there to here. So there’s dispersed matter in the line of sight, but it can account for at most 35% of the dimming. Furthermore, an interstellar cloud would have a hard time maintaining structures small enough to produce the sharp dim-and-recover pattern Boyajian found. Loosely-bound stuff like dust clouds and gas tends to smear out in space.”

“How about comets, or rings, or clumps of asteroids orbiting the star?”

“There’s evidence against all those, but I guess I haven’t mentioned it yet. You’ve seen the heat lamps over Eddie’s pizza bar?”

“Sure. Infrared radiation heats things up.”

“And warm things give off infrared radiation. ‘Warm’ meaning anything above absolute zero. Better yet, there’s a well-known relation between an object’s temperature and its infrared spectrum. Rocks or dust anywhere near the star would absorb energy from whatever kind of light and re-radiate it as heat infrared we could see. The spectrum would show more infrared than you’d expect from the star itself. And there isn’t any extra infrared.”

“None?”

“Not so’s our technology can detect. If there’s any there, it’s less than 0.2% of the total coming from the star, nowhere near enough to account for those 8%, 16% and 22% dips. So no, no comets or rings or asteroid clumps orbiting Tabby’s Star.”

“How about something orbiting our Sun, way far out where we’ve not found it yet?”

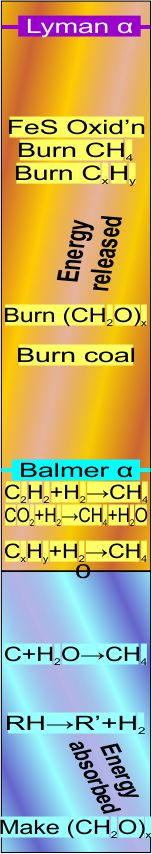

“Any light-blocking object near us, like maybe in the Oort Cloud that sends us long-term comets, should produce the same sort of weirdness from Tabby’s near neighbors. We don’t see that. One astronomer studied a star only 25 arc-seconds away — steady as a rock. So whatever’s causing the dimming is probably close to Tabby’s star. Oh, wait, here’s one more weirdness. I just saw a report…” [twiddles on tablet] “Yeah, here it is. Check out this chart.” “You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

“Sure. The Planet Hunter team was looking for transits, which generally take at most a few days, so the Kepler science team filtered out slow variations before passing the data along. After Boyajian’s report came out, two Keplerians looked back at the raw data. I told you about the 3-6% dimming (estimates vary) since 1890. The raw Kepler data show a 3% drop in four years!”

“I’m starting to think about Dyson Spheres and Larry Niven’s Ringworld.”

“Now you know why SETI got excited.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“If they’re so small, why are they called bears?”

“If they’re so small, why are they called bears?” “Yup, and that’s one way astronomers can classify planets. Earth’s in the Goldilocks Zone for liquid water, essential for life as we know it. Saturn’s moon Titan might support some other kind of life in its

“Yup, and that’s one way astronomers can classify planets. Earth’s in the Goldilocks Zone for liquid water, essential for life as we know it. Saturn’s moon Titan might support some other kind of life in its

The underlying physics is straightforward. The string produces a stable tone only if its motion has nodes at both ends, which means the vibration has to have a whole number of nodes, which means you have to pluck halfway between two of the nodes you want. If you pluck it someplace like 39¼:264.77 then you excite a whole lot of frequencies that fight each other and die out quickly.

The underlying physics is straightforward. The string produces a stable tone only if its motion has nodes at both ends, which means the vibration has to have a whole number of nodes, which means you have to pluck halfway between two of the nodes you want. If you pluck it someplace like 39¼:264.77 then you excite a whole lot of frequencies that fight each other and die out quickly. Add a few more planets in a random configuration and stability goes out the window — but then something interesting happens. It’s

Add a few more planets in a random configuration and stability goes out the window — but then something interesting happens. It’s  The usual rings-around-the-Sun diagram doesn’t show the specialness of the orbits we’ve got. This chart shows the four innermost planets in their “ideal” orbits, properly scaled and with approximately the right phases. I used artistic license to emphasize the gear-like action by reversing Earth’s and Mercury’s direction. Earth and Mars are never near each other, nor are Earth and Venus.

The usual rings-around-the-Sun diagram doesn’t show the specialness of the orbits we’ve got. This chart shows the four innermost planets in their “ideal” orbits, properly scaled and with approximately the right phases. I used artistic license to emphasize the gear-like action by reversing Earth’s and Mercury’s direction. Earth and Mars are never near each other, nor are Earth and Venus.

This video, from an Orbits Table display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows a different Plutonian weirdness. We’re circling the Solar System at about 50 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (50 AU). Reading inward, the white lines represent the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter. The Asteroid Belt is the small greenish ring close to the Sun. The four terrestrial planets are even further in. The Kuiper Belt is the greenish ring that encloses the lot.

This video, from an Orbits Table display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows a different Plutonian weirdness. We’re circling the Solar System at about 50 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (50 AU). Reading inward, the white lines represent the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter. The Asteroid Belt is the small greenish ring close to the Sun. The four terrestrial planets are even further in. The Kuiper Belt is the greenish ring that encloses the lot.

Before you get any further in this post, follow

Before you get any further in this post, follow

This photo, part of the LAMP exhibit at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows why. It’s a model of a cratered Moon lit by sunlight.

This photo, part of the LAMP exhibit at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows why. It’s a model of a cratered Moon lit by sunlight.