“Morning, Al. What’s the scone of the day?”

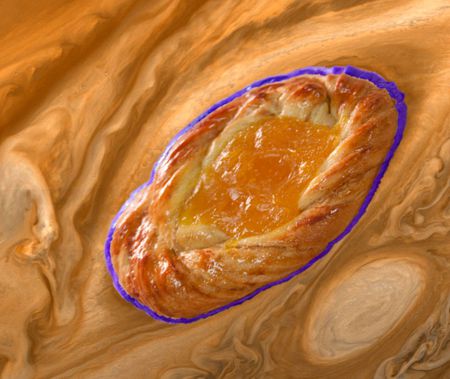

“No scones today, Sy. Cathleen and one of her Astronomy students used my oven to do a whole batch of these orange-and-apricot Danishes. Something to do with Jupiter. Try one.”

Cathleen was standing behind me. “They’re in honor of NASA’s Juno spacecraft. She just completed a close-up survey of Jupiter’s famous cloud formation, the Great Red Spot. Whaddaya think?”

“Not bad. Nice bright color and a good balance of sweetness from the apricot against tartness from the orange.”

“You noticed that, hey? We had to do a lot of balancing — flavors, colors, the right amount of liquid. Too juicy and the pastry part comes out gummy, too dry and you break a tooth. Notice something else?”

“The structure, right? Like the Spot’s collar around a mushed-up center.”

“Close, but Juno showed us that center’s anything but mushed-up. <pulls out her smartphone> Here’s what she sent back.”

“See, it’s swirls within swirls. We tried stirring the filling to look like that but it mostly smoothed out in the baking.”

“Hey, is it true what I heard that the Great Red Spot has been there for 400 years?”

“We think so, Al, but nobody knows for sure. When Galileo published his telescopic observations of Jupiter in 1610 he didn’t mention a spot. But that could be because he’d already caught flak from the Church by describing mountains and craters on the supposedly perfect face of the Moon. Besides, the Jovian moons he saw were much more exciting for the science of the time. A planet with satellites was a direct contradiction to Aristotle’s Earth-centered Solar System.”

“OK, but what about after Galileo?”

“There are records of a spot between 1665 and 1713 but then no reports of a spot for more than a century. Maybe it was there and nobody was looking for it, maybe it had disappeared. But Jupiter’s got one now and it’s been growing and shrinking for the past 185 years.”

“So what is it, what’s it made of and why’s it been there so long?”

“Three questions, one of them easy.”

“Which is easy, Sy?”

“The middle one. The answer is, no-one knows what it’s made of. That’s part of Juno‘s mission, to do close-up spectroscopy and help us wheedle what kinds of molecules are in there. We know that Jupiter’s mostly hydrogen and helium, just like the Sun, but both of those are colorless. Why some of the planet’s clouds are blue and some are pink — that’s a puzzle, right, Cathleen?”

“Well, we know a little more than that, especially since the Galileo probe dove 100 miles into the clouds in 1995. The white clouds are colder and made of ammonia ice particles. The pink clouds are warmer and … ok, we’re still working on that.”

“What about my other two questions, Cathleen?”

“People often call it a hurricane, but that’s a misnomer. On Earth, a typical hurricane is a broad, complex ring of rainstorms with wind speeds from 75 to 200 mph. Inside the ring wall people say it’s eerily calm. The whole thing goes counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere, clockwise in the southern one.”

“So how’s the Great Red Spot different?”

“Size, speed, complexity, even direction. East-to-west, the Spot is eight times wider than the biggest hurricanes. Its collar winds run about 350 mph and it rotates counterclockwise even though it’s in Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. It’s like a hurricane inside-out.”

“It’s not calm inside?”

“Nope, take another look at that Juno image. There’s at least three very busy bands wrapped around a central structure that looks like it holds three distinct swirls. That’s the part that’s easiest to understand.”

“Why so?”

“Geometry. Adjacent segments of separate swirls have to be moving in the same direction or they’ll cancel each other out. <scribbles diagram on a paper napkin> Suppose I’ve got just one inside another one. If they go in the same direction the faster one speeds up the slower one and they merge. If they go in opposite directions, one of them disappears. If there’s more than one inner swirl, there has to be an odd number, see?”

“So if it’s not a hurricane, what is it?”

“Got any donuts, Al?”

~~ Rich Olcott

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

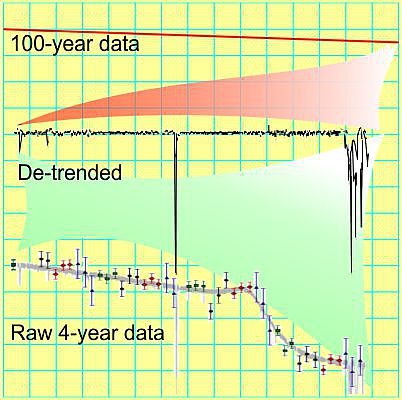

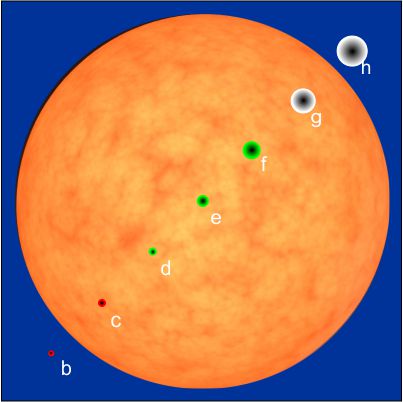

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.”

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.” “How so?”

“How so?”

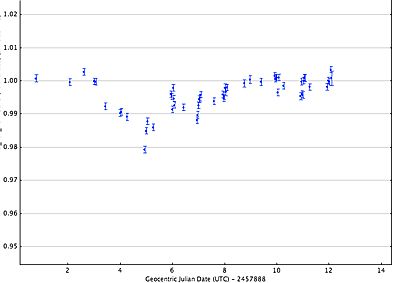

Before you get any further in this post, follow

Before you get any further in this post, follow

This photo, part of the LAMP exhibit at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows why. It’s a model of a cratered Moon lit by sunlight.

This photo, part of the LAMP exhibit at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows why. It’s a model of a cratered Moon lit by sunlight.

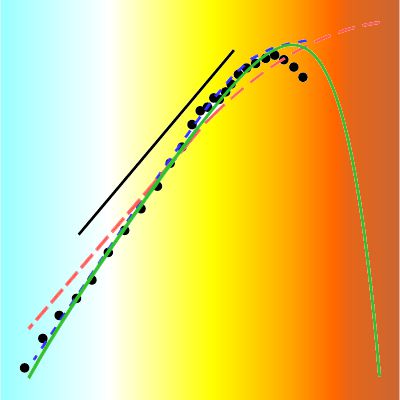

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

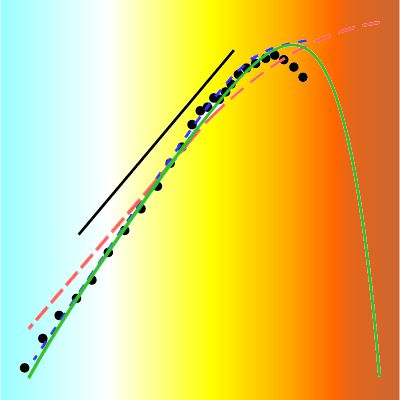

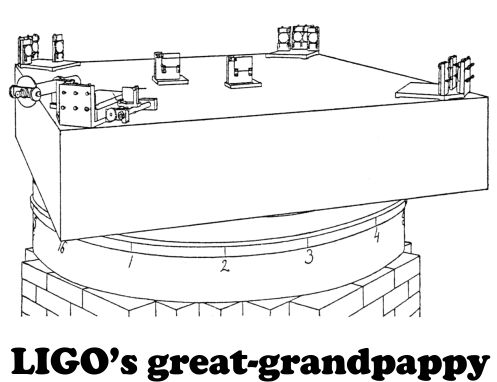

The second question is harder. The best the aLIGO team could do was point to a “banana-shaped region” (their words, not mine) that covers about 1% of the sky. The team marshaled a world-wide collaboration of observatories to scan that area (a huge search field by astronomical standards), looking for electromagnetic activities concurrent with the event they’d seen. Nobody saw any. That was part of the evidence that this collision involved two black holes. (If one or both of the objects had been something other than a black hole, the collision would have given off all kinds of photons.)

The second question is harder. The best the aLIGO team could do was point to a “banana-shaped region” (their words, not mine) that covers about 1% of the sky. The team marshaled a world-wide collaboration of observatories to scan that area (a huge search field by astronomical standards), looking for electromagnetic activities concurrent with the event they’d seen. Nobody saw any. That was part of the evidence that this collision involved two black holes. (If one or both of the objects had been something other than a black hole, the collision would have given off all kinds of photons.) In contrast, a LIGO facility is (roughly speaking) omni-directional. When a LIGO installation senses a gravitational pulse, it could be coming down from the visible sky or up through the Earth from the other hemisphere — one signal doesn’t carry the “which way?” information. The diagram above shows that situation. (The “chevron” is an image of the LIGO in Hanford WA.) Models based on the signal from that pair of 4-km arms can narrow the source field to a “banana-shaped region,” but there’s still that 180o ambiguity.

In contrast, a LIGO facility is (roughly speaking) omni-directional. When a LIGO installation senses a gravitational pulse, it could be coming down from the visible sky or up through the Earth from the other hemisphere — one signal doesn’t carry the “which way?” information. The diagram above shows that situation. (The “chevron” is an image of the LIGO in Hanford WA.) Models based on the signal from that pair of 4-km arms can narrow the source field to a “banana-shaped region,” but there’s still that 180o ambiguity. The great “if only” is that the VIRGO installation in Italy was not recording data when the Hanford WA and Livingston LA saw that September signal. With three recordings to reconcile, the aLIGO+VIRGO combination would have had enough information to slice that banana and localize the event precisely.

The great “if only” is that the VIRGO installation in Italy was not recording data when the Hanford WA and Livingston LA saw that September signal. With three recordings to reconcile, the aLIGO+VIRGO combination would have had enough information to slice that banana and localize the event precisely.

We can investigate things that take longer than an instrument’s characteristic time by making repeated measurements, but we can’t use the instrument to resolve successive events that happen more quickly than that. We also can’t resolve events that take place much closer together than the instrument’s characteristic length.

We can investigate things that take longer than an instrument’s characteristic time by making repeated measurements, but we can’t use the instrument to resolve successive events that happen more quickly than that. We also can’t resolve events that take place much closer together than the instrument’s characteristic length.