The local science museum had a showing of the Christopher Nolan film Interstellar so of course I went to see it again. Awesome visuals and (mostly) good science because Nolan had tapped the expertise of Dr Kip Thorne, one of the primary creators of LIGO. On the way out, Vinnie collared me.

“Hey, Sy, ‘splain something to me.”

“I can try, but first let’s get out of the weather. Al’s coffee OK with you?”

“Yeah, sure, if his scones are fresh-baked.”

Al saw me walking in. “Hey, Sy, you’re in luck, I just pulled a tray of cinnamon scones out of the oven.” Then he saw Vinnie. “Aw, geez, there go my paper napkins again.”

Vinnie was ready. “Nah, we’ll use the backs of some ad flyers I grabbed at the museum. And gimme, uh, two of the cinnamons and a large coffee, black.”

“Here you go.”

At our table I said, “So what’s the problem with the movie?”

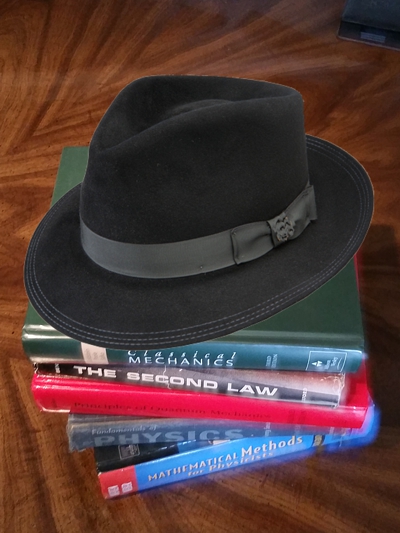

“Nobody shrank. All this time we been talking about how things get smaller in a strong gravity field. That black hole, Gargantua, was huge. The museum lecture guy said it was like 100 million times as heavy as the Sun. When the people landed on its planet they should have been teeny but everything was just regular-size. And what’s up with that ‘one hour on the planet is seven years back home’ stuff?”

“OK, one thing at a time. When the people were on the planet, where was the movie camera?”

“On the planet, I suppose.”

“Was the camera influenced by the same gravitational effects that the people were?”

“Ah, it’s the frames thing again, ain’t it? I guess in the on-planet inertial frame everything stays the relative size they’re used to, even though when we look at the planet from our far-away frame we see things squeezed together.”

(I’ve told you that Vinnie’s smart.) “You got it. OK, now for the time thing. By the way, it’s formally known as ‘time dilation.’ Remember the potential energy/kinetic energy distinction?”

“Yeah. Potential energy depends on where you are, kinetic energy depends on how you’re moving.”

“Got it in one. It turns out that energy and time are deeply intertwined all through physics. Would you be surprised if I told you that there are two kinds of time dilation, one related to gravitational potential and the other to velocity?”

“Nothing would surprise me these days. Go on.”

“The gravity one dropped out of Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity. The velocity one arose from his General Relativity work.” I grabbed one of those flyers. “Ready for a little algebra?”

“Geez. OK, I asked for it.”

“You certainly did. I’ll just give you the results, and mind you these apply only near a non-rotating sphere with no electric charge. Things get complicated otherwise. Suppose the sphere has mass M and you’re circling around it at a distance r from its geometric center. You’ve got a metronome ticking away at n beats per your second and you’re perfectly happy with that. We good?”

“So far.”

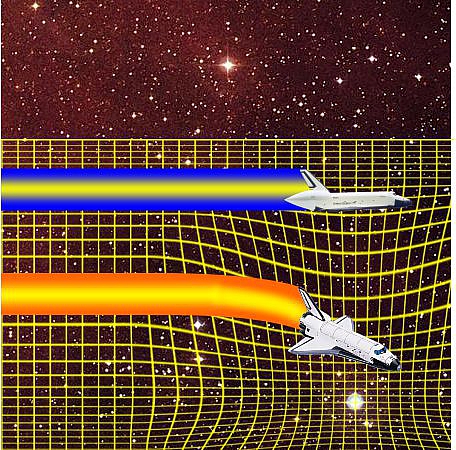

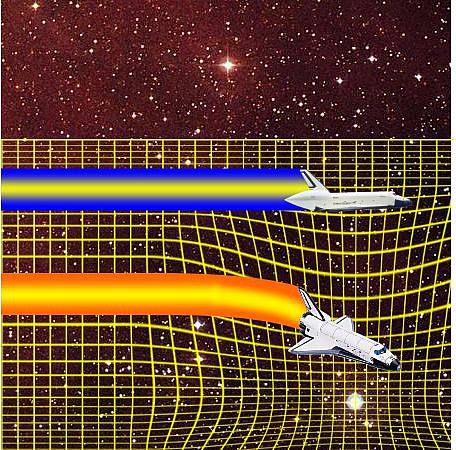

“I’m watching you from way far away. I see your metronome running slow, at only n√[1-(2 G·M/r·c²)] beats per my second. G is Newton’s gravity constant, c is the speed of light. See how the square root has to be less than 1?”

“Your speed of light or my speed of light?”

“Good question, considering we’re talking about time and space getting all contorted, but Einstein guarantees that both of us measure exactly the same speed. So anyway, in the movie both the Miller’s Planet landing team and that poor guy left on good ship Endurance are circling Gargantua. Earth observers would see both their clocks running slow. But Endurance is much further out (larger r, smaller fraction) from Gargantua than Miller’s Planet is. Endurance’s distance gave its clock more beats per Earth second than the planet gets, which is why the poor guy aged so much waiting for the team to return.”

“I wondered about that.”

Then we heard Ramona’s husky contralto. “Hi, guys. Al said you were back here talking physics. Who wants to take me dancing?”

We both stood up, quickly.

“Whee, this’ll be fun.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“OK,

“OK,

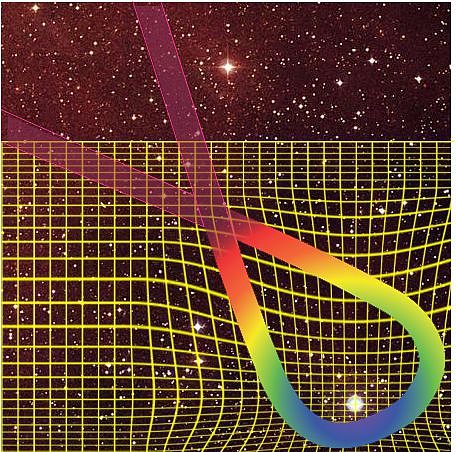

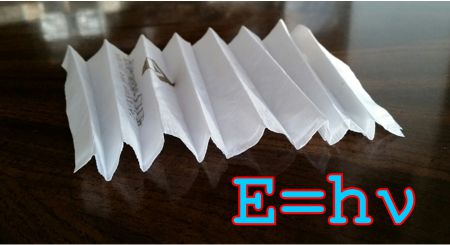

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”