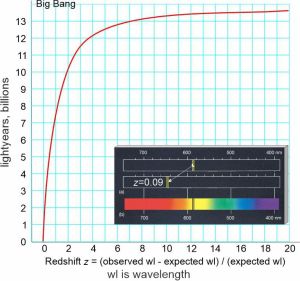

“Y’know, Cathleen, both our ladders boil down to time. Your Astronomy ladder connects objects at different times in the history of the Universe. My Geology ladder looks back into the Solar System’s history.”

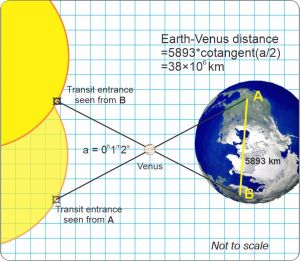

“As an astronomer I normally think of parsecs or lightyear distances but you have a point, Kareem. Edwin Hubble linked astronomical space with time. Come to think of it, my cosmologist colleagues work almost exclusively in the time domain, like ‘T=0 plus a few lumptiseconds.’ Billions of years down to that teeny time interval — how does your time ladder compare?”

“Lumptiseconds out to a hundred trillion times the age of the Universe. I win.”

“C’mon, Kareem.”

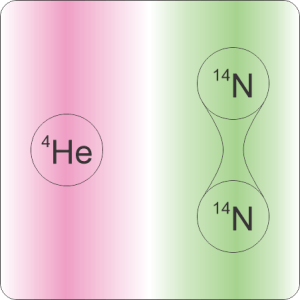

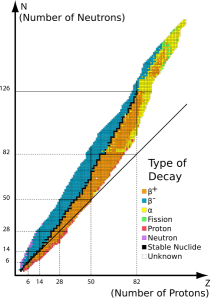

“No, really, Sy. My ladder uses isotopes. Every carbon atom has 6 protons in the nucleus, right? Carbon‑12 adds 6 neutrons and it’s stable but another isotope, carbon‑14, has 8 neutrons. It’s radioactive — spits out an electron and becomes stable nitrogen‑14 with 7 and 7. Really heavy isotopes like uranium‑238 spit out alpha particles.”

“Wait, if carbon‑14 spits out an electron doesn’t that make it a carbon ion?”

“Uh‑uh, Cathleen, the electron comes out of the nucleus, not the electron cloud. It’s got a hundred thousand times more energy than a chemical kick could give it. Sy could explain—”

“Nice try, Kareem, this is your geologic time story. Let’s stay with that.”

“If I must. So, the stable isotopes last forever, pretty much, but the radioactive ones are ticking bombs with random detonation times.”

“What’s doing the ticking? Surely there’s no springs or pendulums in there.”

“Quantum, Cathleen. Sy’s trying to stay out of this so I’ll give you my outsider answer. I picture every kind of subatomic particle constantly trying to leave every nucleus, butting their little heads bazillions of times a second against walls set up by the weak and strong nuclear forces. Nearly every try is a bounce‑back, but one success is enough to break the nucleus. Every isotope has its own personal set of parameters for each kind of particle — wall height, wall thickness, something like an internal temperature ruling how hard the particles hit the walls. The ticking is those head‑butts; the randomness comes from quantum’s goofy rules somehow. How’s that, Sy?”

“Good enough for jazz, Kareem. Carry on.”

“Right. So every kind of radioisotope is characterized by what kinds of particle it emits, how much energy each kind has after busting through a wall, and how often that happens in a given sample size. And the isotope’s chemistry, of course, which is the same as every other isotope that has the same number of protons. The general rule is that the stable isotopes have maybe a few more neutrons than protons but nearly every element has some unstable isotopes. The ones with too many neutrons, like carbon‑14, emit electrons as beta particles. They go up a square in the Periodic Table. Too few and they drop down by emitting a positron.”

“All those radioactive stand‑ins for normal atoms. Sounds ghastly. Why are we still here and not all burnt up?”

“First, when one of these atoms decays by itself it’s a lot of energy for that one atom, but the energy spreads out as heat across many atoms. Unless a bunch of atoms crumble at about the same time, there’s only a tiny bit of general heating. The major biological danger from radioactivity comes from spit‑out particles breaking protein or DNA molecules.”

“Mutated, not burnt.”

“Mm‑hm. Second, the radioactives are generally rare relative to their stable siblings. In many cases that’s because the bad guys, like aluminum‑26, have had time to decay to near‑zero. That banana you’re eating has about half a gram of potassium atoms but only 0.012% are unstable potassium‑40. Third, an isotope with a long half‑life doesn’t lose many atoms per unit time. A kilogram of tellurium‑128, for instance, loses 2000 atoms per year. The potassium‑40 in your banana has a half‑life of nearly 2 million years. Overall, it releases only about 1300 beta particles per second producing less than a nanowatt of heat‑you‑up power. Not to worry.”

“Two million years? How do you measure something that slow?”

~~ Rich Olcott