Vinnie lifts his pizza slice and pauses. “I dunno, Sy, this Pressure‑Volume part of enthalpy, how is it energy so you can just add or subtract it from the thermal and chemical kinds?”

“Fair question, Vinnie. It stumped scientists through the end of Napoleon’s day until Sadi Carnot bridged the gap by inventing thermodynamics.”

“Sounds like a big deal from the way you said that.”

“Oh, it was. But first let’s clear the ‘is it energy?’ question. How would Newton have calculated the work you did lifting that slice?”

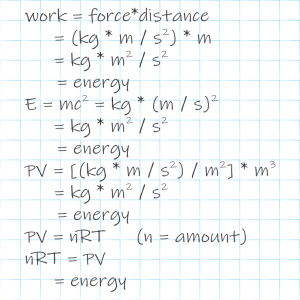

“How much force I used times the distance it moved.”

“Putting units to that, it’d be force in newtons times distance in meters. A newton is one kilogram accelerated by one meter per second each second so your force‑distance work there is measured in kilograms times meters‑squared divided by seconds‑squared. With me?”

“Hold on — ‘per second each second’ turned into ‘per second‑squared.” <pause> “Okay, go on.”

“What’s Einstein’s famous equation?”

“Easy, E=mc².”

“Mm-hm. Putting units to that, c is in meters per second, so energy is kilograms times meters‑squared divided by seconds‑squared. Sound familiar?”

“Any time I’ve got that combination I’ve got energy?”

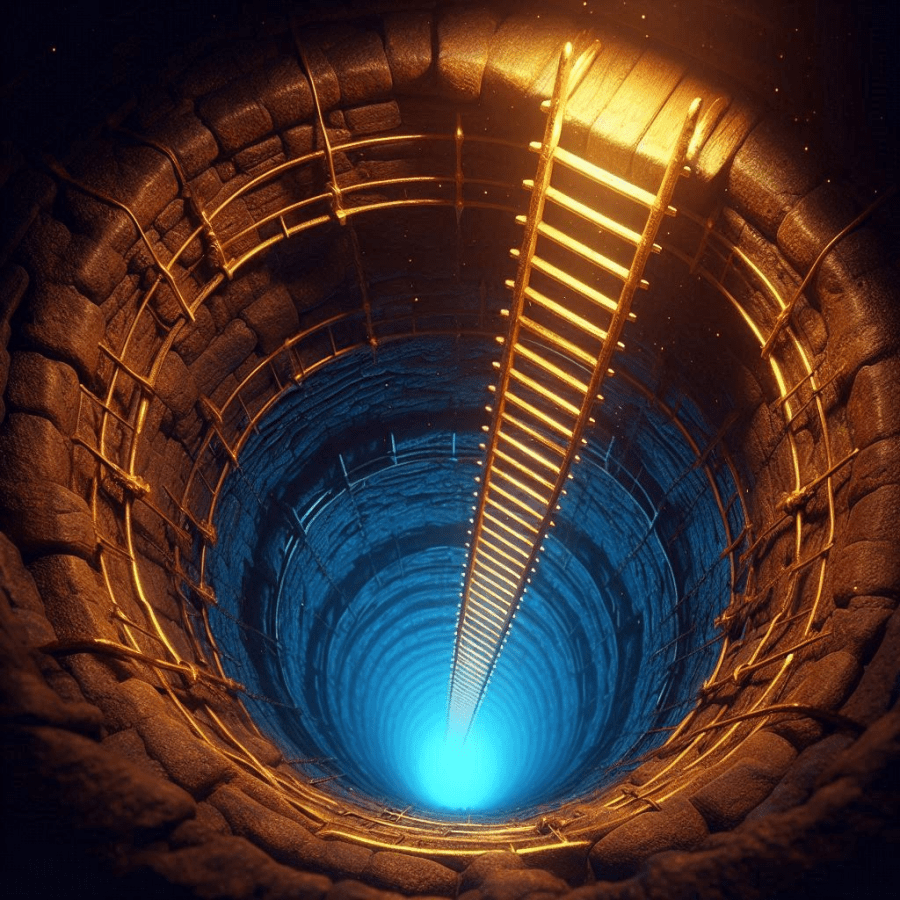

“Mostly. Here’s another example — a piston under pressure. Pressure is force per unit area. The piston’s area is in square meters so the force it feels is newtons per meter‑squared, times square meters, or just newtons. The piston travels some distance so you’ve got newtons times meters.”

“That’s force‑distance work units so it’s energy, too.”

“Right. Now break it down another way. When the piston travels that distance, the piston’s area sweeps through a volume measured in meters‑cubed, right?”

“You’re gonna say pressure times volume gives me the same units as energy?”

“Work it out. Here’s a paper napkin.”

“Dang, I hate equations … Hey, sure enough, it boils down to kilograms times meters‑squared divided by seconds‑squared again!”

“There you go. One more. The Ideal Gas Law is real simple equation —”

“Gaah, equations!”

“Bear with me, it’s just PV=nRT.”

“Is that the same PV so it’s energy again?”

“Sure is. The n measures the amount of some gas, could be in grams or whatever. The R, called the Gas Constant, is there to make the units come out right. T‘s the absolute temperature. Point is, this equation gives us the basis for enthalpy’s chemical+PV+thermal arithmetic.”

“And that’s where this Carnot guy comes in.”

“Carnot and a host of other physicists. Boyle, Gay‑Lussac, Avagadro and others contributed to Clapeyron’s gas law. Carnot’s 1824 book tied the gas narrative to the energetics narrative that Descartes, Leibniz, Newton and such had been working on. Carnot did it with an Einstein‑style thought experiment — an imaginary perfect engine.”

“Anything perfect is imaginary, I know that much. How’s it supposed to work?”

<sketching on another paper napkin> “Here’s the general idea. There’s a sealed cylinder in the middle containing a piston that can move vertically. Above the piston there’s what Carnot called ‘a working body,’ which could be anything that expands and contracts with temperature.”

“Steam, huh?”

“Could be, or alcohol vapor or a big lump of iron, whatever. Carnot’s argument was so general that the composition doesn’t matter. Below the piston there’s a mechanism to transfer power from or to the piston. Then we’ve got a heat source and a heat sink, each of which can be connected to the cylinder or not.”

“Looks straight‑forward.”

“These days, sure. Not in 1824. Carnot’s gadget operates in four phases. In generator mode the working body starts in a contracted state connected to the hot Th source. The body expands, yielding PV energy. In phase 2, the body continues to expand while it while it stays at Th. Phase 3, switch to the cold Tc heat sink. That cools the body so it contracts and absorbs PV energy. Phase 4 compresses the body to heat it back to Th, completing the cycle.”

“How did he keep the phases separate?”

“Only conceptually. In real life Phases 1 and 2 would occur simultaneously. Carnot’s crucial contribution was to treat them separately and yet demonstrate how they’re related. Unfortunately, he died of scarlet fever before Clapeyron and Clausius publicized and completed his work.”

~ Rich Olcott