<ding/ding/ding> <yawn> “Who’s texting me at this time of night?”

This better be good.

Hi, Uncle Sy. Did I wake you up?

At this hour? Of course you did, Teena. What’s going on?

Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t realize what time it is. I’ve been deep into my Chemistry homework. There’s a question here that I don’t understand and I thought you could help me with. Please?

Well, I’m awake. What’s the question?

This isn’t quite what they ask but it’s what I’m stuck on. Is energy stepwise or continuous?

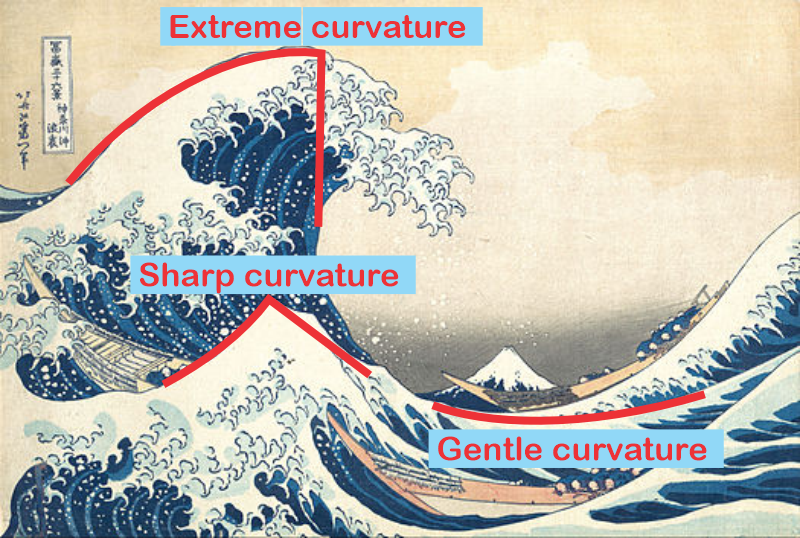

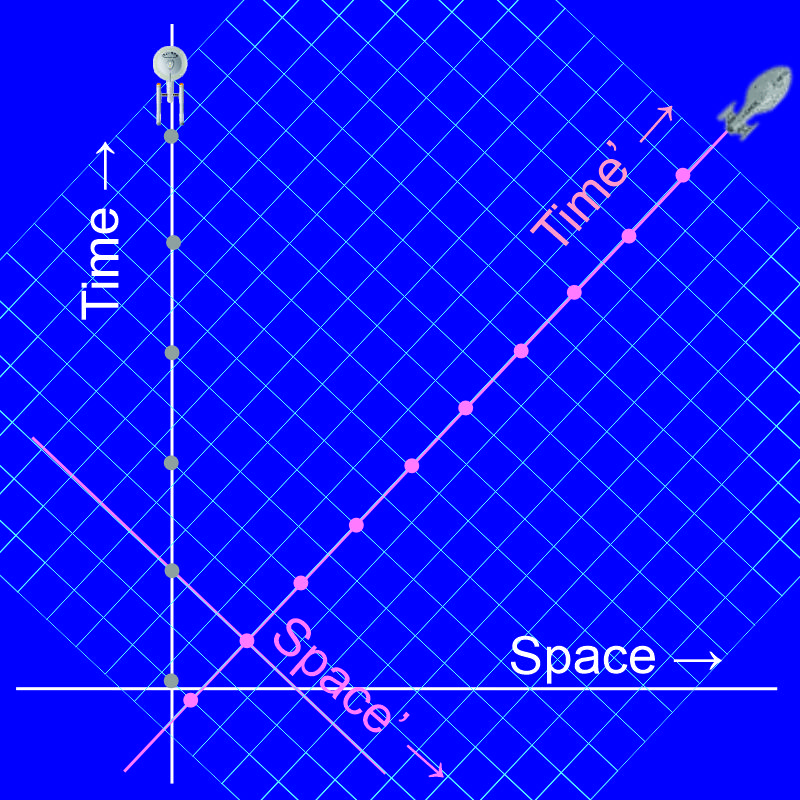

Whoa! That’s not really an either‑or proposition. Energy is continuous, but the energy differences that atoms/molecules respond to are stepwise. You get continuous white light from hot objects like stars and welding torches.

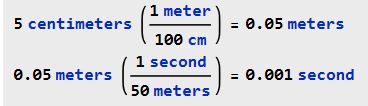

If white light passes a hydrogen atom, the atom will only absorb certain specific frequencies (frequency is a measure of energy).

The rest bounce off, creating the atom’s…line spectrum?

Yes, except they don’t bounce off, they pass by.

The more energy/heat fire has, the further down the EM spectrum its light goes: red, orange, yellow, blue, white. Is that correct?

Mostly, though the usual sequence read ‘upward’ in energy is radio, microwave, infrared, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays.

White is an even mixture of all frequencies.

I was focusing on the visible section for a reason.

Mmm?

So, there’s red, orange, yellow, and blue fire in order of how much heat it has, why does it skip purple and green? A normal fire can reach red, orange, yellow just fine with the only difference being heat, but why can’t fire be green or purple without throwing chemicals in it?

Ah, what you’re really looking at is variation in fuel/air mixture (and possibly which fuel — I’ll get to that).

A rich methane mixture (not much oxygen, like a shuttered Bunsen burner) doesn’t get very hot, has lots of unburnt carbon particles and looks orange. Add more oxygen and the flame gets hotter, no more soot particles, just isolated CO, CO2, and water molecules, each of which gets excited to flame temp and then radiates light but only at its own characteristic frequencies. Switch to acetylene fuel and the flame gets hotter still because C2H2+O2 reactions give off more energy per molecule than CH4+O2. Now you’re in plasma temperature range, where free electrons can emit whatever frequency they feel like.

How about sunsets and campfires?

Sunsets are a whole other thing — the sun’s white light is transformed in various ways as it filters through dust and such in the atmosphere. Anyway, no flame or atom/molecule excitation in a sunset

But it all comes down to how much energy the light source “has”, right? That’s what I think I remember from physics. And what about campfires? In the center of the fire you have blue flame, and the further from the center the closer to red flame you get, but it still skips green!

Yes, but in each of these cases the *source* is different — soot particles, excited molecules, plasma.

???

The campfire has several different processes going on. Close in, the heated wood emits various gases. The gases reacting with O2 *are* the flame, generally orange to yellow from excited molecules but you can get blue where the local ventilation forms a jet and brings in extra oxygen for an efficient flame. Further out it’s back to red-hot soot.

OK

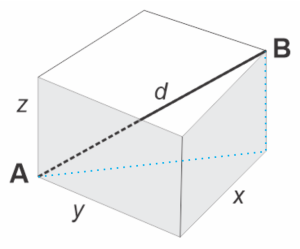

To your original question — this is a hypothesis, but I suspect the particular atoms and molecules emitted from untreated burning wood simply don’t have any strong emissions lines in the green region. I know there aren’t for any hydrogen atoms — look up “Balmer series” in wikipedia.

Thanks for talking me through this. I understand it better now. Continuous spectrums come from hot electrons, but line spectrums come from different atoms or molecules. Right?

*spectra

Right.

As you said, you could throw in copper or sodium salts to get those blue and golden colors.

I figured there had to be some way to go about it – I’ve seen lots of green and gold (YAY CSU!) fireworks. G’night, Uncle Sy.

G’night, Teena.

Now get to bed.

~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Alex, who wrote much of this.