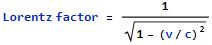

“Wait, Sy, there’s something funny about that Lorentz factor. I’m riding my satellite and you’re in your spaceship to Mars and we compare notes and get different times and lengths and masses and all so we have to use the Lorentz factor to correct numbers between us. Which velocity do we use, yours or mine?”

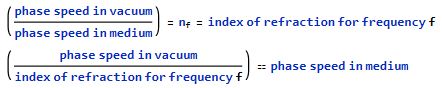

“Good question, Vinnie. We use the difference between our two frames. We can subtract either velocity from the other one and replace v with that number. Strictly speaking, we’d subtract velocity components perpendicular to the vector between us. If I were to try to land on your satellite I’d have to expend fuel and energy to change my frame’s velocity to yours. When we matched frames the velocity difference would be zero, the Lorentz factor would be 1.0 and I’d see your solar array as a perfect 10×10‑meter square. Our clocks would tick in sync, too.”

“OK, now there’s another thing. That Lorentz formula compares our subtracted speeds to lightspeed c. What do we subtract to get c?”

“Deep question. That’s one of Einstein’s big insights. Suppose from my Mars‑bound spaceship I send out one light pulse toward Mars and another one in the reverse direction, and you’re watching from your satellite. No matter how fast my ship is traveling, Einstein said that you’d see both pulses, forward and backward, traveling at the same speed, c.”

“Wait, shouldn’t that be that your speed gets added to one pulse and subtracted from the other one?”

“Ejected mass works that way, but light has no mass. It measures its speed relative to space itself. What you subtract from c is zero. Everywhere.”

“OK, that’s deep. <pause> But another ‘nother thing—”

“For a guy who doesn’t like equations, you’re really getting into this one.”

“Yeah, as I get up to speed it grows on me. HAW!”

“Nice one, you got me. What’s the ‘nother thing?”

“I remembered how velocity is speed and direction but we’ve been mixing them together. If my satellite’s headed east and your spaceship’s headed west, one of us is minus to the other, right? We’re gonna figure opposite v‑numbers. How’s that work out?”

“You’re right. Makes no difference to the Lorentz factor because the square of a negative difference is the same as the square of its positive twin. You bring up an important point, though — the factor applies to both of us. From my frame, your clock is running slow. From your frame, mine’s the slow one. Einstein’s logic says we’re both right.”

“So we both show the same wrong time, no problem.”

“Nope, you see my clock running slow relative to your clock. I see exactly the reverse. But it gets worse. How about getting your pizza before you order it?”

“Eddie’s good, he ain’t that good. How do you propose to make that happen?”

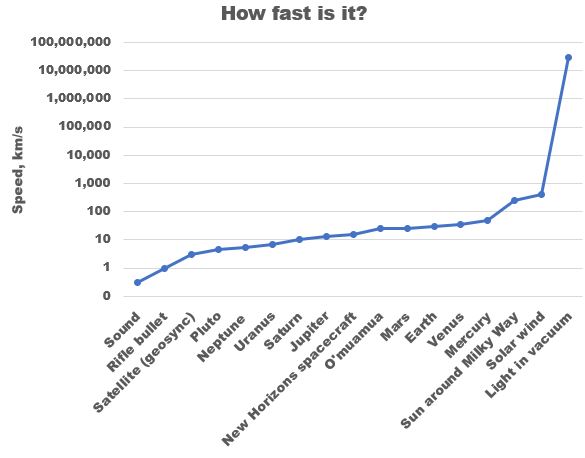

“Well, I don’t, but follow me here. <working numbers on Old Reliable> Suppose we’re both in spaceships. I’m loafing along at 0.75c relative to Eddie’s pizza place on Earth and your ship is doing 3c. Also, suppose that we can transmit messages and mass much faster than lightspeed.”

“Like those Star Trek transporters and subspace radios.”

“Right. OK, at noon on my personal clock you tell me you’ve ordered pizza so I get one, too. Eddie slaps both our pizzas into his transporter 10 minutes later. The math works out that according to my clock you get your pizza 8.9 minutes before you put in your order. You like that?”

“Gimme a sec … nah, I don’t think so. If I read that formula right with v1 being you and v2 being me, if you run that formula for what I’d see with my velocity on the bottom, that’s a square root of a minus which can’t be right.”

“Yup, the calculation gives an imaginary number, 4.4i minutes, whatever that means. So between us we have two results that are just nonsense — I see effect before cause and you see a ridiculous time. To avoid that sort of thing, Einstein set his speed limit for light, gravity and information.”

“I’m willing to keep under it if you are.”

“Deal.”

~~ Rich Olcott