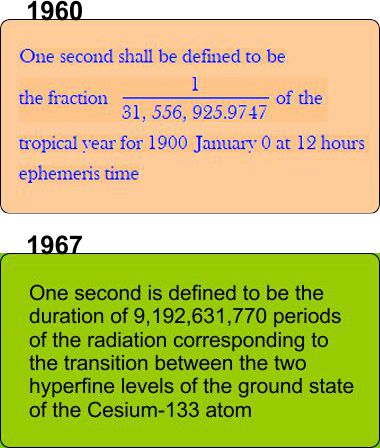

Vinnie’s fiddling with his Pizza Eddie’s pizza crumbs. “Hey, Sy, so we got the time standard switched over from that faked 1900 Sun to counting lightwave peaks in a laser beam. I understand why that’s more precise ’cause it’s a counting measure, and it’s repeatable and portable ’cause they can set up a time laser on Mars or wherever that uses the same identical kinds of atoms to do the frequency stuff. All this talk I hear about spacetime, I’m thinkin’ space is linked to time, right? So are they doing smart stuff like that for measuring space?”

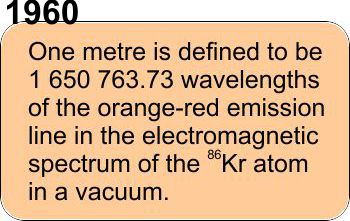

“They did in 1960, Vinnie. Before that the meter was defined to be the distance between two carefully positioned scratches on a platinum-iridium bar that was lovingly preserved in a Paris basement vault. In 1960 they went to a new standard. Here, I’ll bring it up on Old Reliable. By the way, it’s spelled m-e-t-e-r stateside, but it’s the same thing.”

“Mmm… Something goofy there. Look at the number. You’ve been going on about how a counted standard is more precise than one that depends on ratios. How can you count 0.73 of a cycle?”

“You can’t, of course, but suppose you look at 100 meters. Then you’d be looking at an even 165,076,373 of them, OK?”

“Sorta, but now you’re counting 165 million peaks. That’s a lot to ask even a grad student to do, if you can trust him.”

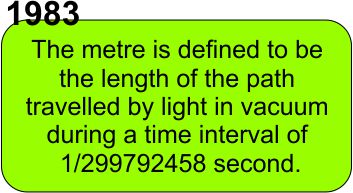

“He won’t have to. Twenty-three years later they went to this better definition.”

“Wait, that depends on how accurate we can measure the speed of light. We get more accurate, the number changes. Doesn’t that get us into the ‘different king, different foot-size’ hassle?”

“Quite the contrary. It locks down the size of the unit. Suppose we develop technology that’s good to another half-dozen digits of precision. Then we just tack half-a-dozen zeroes onto that fraction’s denominator after its decimal point. Einstein said that the speed of light is the same everywhere in the Universe. Defining the meter in terms of lightspeed gives us the same kind of good-everywhere metric for space that the atomic clocks give us for time.”

“I suppose, but that doesn’t really get us past that crazy-high count problem.”

“Actually, we’ve got three different strategies for different length scales. For long distances we just use time-of-flight. Pick someplace far away and bounce a laser pulse off of it. Use an atomic clock to measure the round-trip time. Take half that, divide by the defined speed of light and you’ve got the distance in meters. Accuracy is limited only by the clock’s resolution and the pulse’s duration. The Moon’s about a quarter-million miles away which would be about 2½ seconds round-trip. We’ve put reflectors up there that astronomers can track to within a few millimeters.”

“Fine, but when distances get smaller you don’t have as many clock-ticks to work with. Then what do you do?”

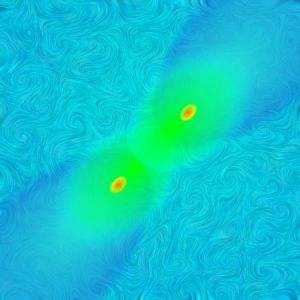

“You go to something that doesn’t depend on clock-ticks but is still connected to that constant speed of light. Here, this video on Old Reliable ought to give you a clue.”

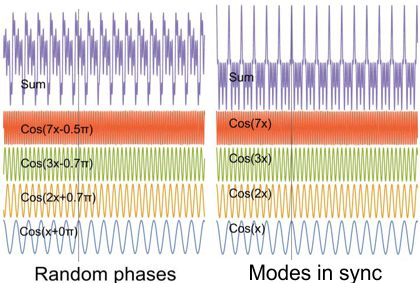

“OK, the speed which is a constant is the number of peaks that’s the frequency times the distance between them that’s the wavelength. If I know a wavelength then arithmetic gets me the frequency and vice-versa. Fine, but how do I get either one of them?”

“How do you tune a trombone?”

“Huh? I suppose you just move the slide until you get the note you want.”

“Yup, if a musician has good ear training and good muscle memory they can set the trombone’s resonant tube length to play the right frequency. Table-top laser distance measurements use the same principle. A laser has a resonant cavity between two mirrors. Setting the mirror-to-mirror distance determines the laser’s output. When you match the cavity length to something you want to measure, the laser beam frequency tells you the distance. At smaller scales you use interference techniques to compare wavelengths.”

Vinnie gets a gleam in his eye. “Time-of-flight measurement, eh?” He flicks a pizza crumb across the room.

In a flash Eddie’s standing over our table. “Hey, hotshot, do that again and you’re outta here!”

“Speed of light, Sy?”

“Pretty close, Vinnie.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“OK,

“OK,

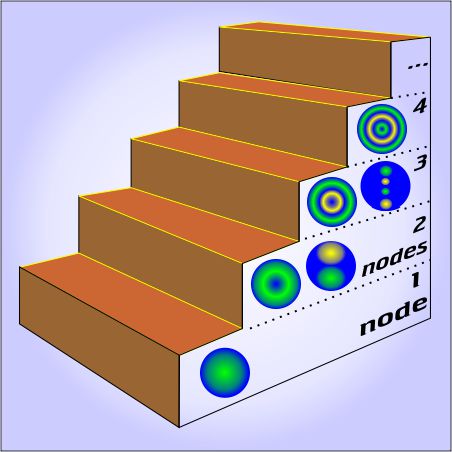

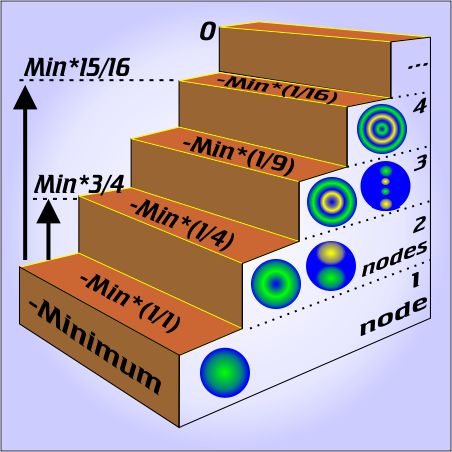

The underlying physics is straightforward. The string produces a stable tone only if its motion has nodes at both ends, which means the vibration has to have a whole number of nodes, which means you have to pluck halfway between two of the nodes you want. If you pluck it someplace like 39¼:264.77 then you excite a whole lot of frequencies that fight each other and die out quickly.

The underlying physics is straightforward. The string produces a stable tone only if its motion has nodes at both ends, which means the vibration has to have a whole number of nodes, which means you have to pluck halfway between two of the nodes you want. If you pluck it someplace like 39¼:264.77 then you excite a whole lot of frequencies that fight each other and die out quickly. Add a few more planets in a random configuration and stability goes out the window — but then something interesting happens. It’s

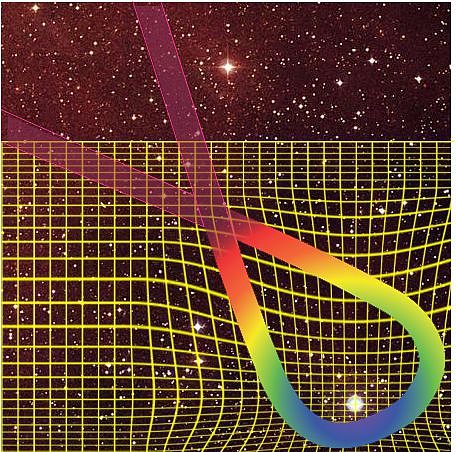

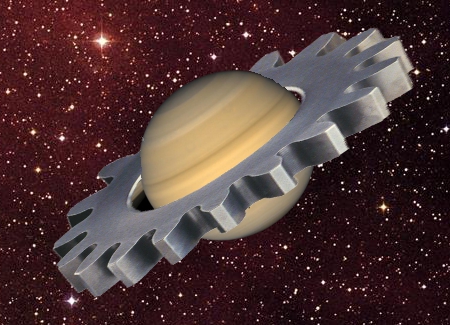

Add a few more planets in a random configuration and stability goes out the window — but then something interesting happens. It’s  The usual rings-around-the-Sun diagram doesn’t show the specialness of the orbits we’ve got. This chart shows the four innermost planets in their “ideal” orbits, properly scaled and with approximately the right phases. I used artistic license to emphasize the gear-like action by reversing Earth’s and Mercury’s direction. Earth and Mars are never near each other, nor are Earth and Venus.

The usual rings-around-the-Sun diagram doesn’t show the specialness of the orbits we’ve got. This chart shows the four innermost planets in their “ideal” orbits, properly scaled and with approximately the right phases. I used artistic license to emphasize the gear-like action by reversing Earth’s and Mercury’s direction. Earth and Mars are never near each other, nor are Earth and Venus.