“Things are finally slowing down. You folks got an interesting talk going, mind if I join you? I got biscotti.”

“Pull up a chair, Eddie. You know everybody?”

“You and Jeremy, yeah, but the young lady’s new here.”

“I’m Jennie, visiting from England.”

“Pleased to meetcha. So from what I overheard, we got Jeremy on some kinda Quest to a black hole’s crust. He’s passed two Perils. There’s a final one got something to do with a Firewall.”

“One minor correction, Eddie. He’s not going to a crust, because a black hole doesn’t have one. Nothing to stand on or crash into, anyway. He’s headed to its Event Horizon, which is the next best thing. If you’re headed inward, the Horizon marks the beginning of where it’s physically impossible to get out.”

“Hotel California, eh?”

“You could say that. The first two Perils had to do with the black hole’s intense gravitational field. The one ahead has to do with entangled virtual particles.”

“Entangled is the Lucy-and-Ethel thing you said where two particles coordinate instant-like no matter how far apart they are?”

“Good job of overhearing, there, Eddie. Jeremy, tell him abut virtual particles.”

“Umm, Mr Moire and I talked about a virtual particle snapping into and out of existence in empty space so quickly that the long-time zero average energy isn’t affected.”

“What we didn’t mention then is that when a virtual pair is created, they’re entangled. Furthermore, they’re anti-particles, which means that each is the opposite of the other — opposite charge, opposite spin, opposite several other things. Usually they don’t last long — they just meet each other again and annihilate, which is how the average energy stays at zero. Now think about creating a pair of virtual particles in the black hole’s intense gravitational field where the creation event sends them in opposite directions.”

“Umm… if they’re on opposite paths then one’s probably headed into the Horizon and the other is outbound. Is the outbound one Hawking radiation? Hey, if they’re entangled that means the inbound one still has a quantum connection with the one that escaped!”

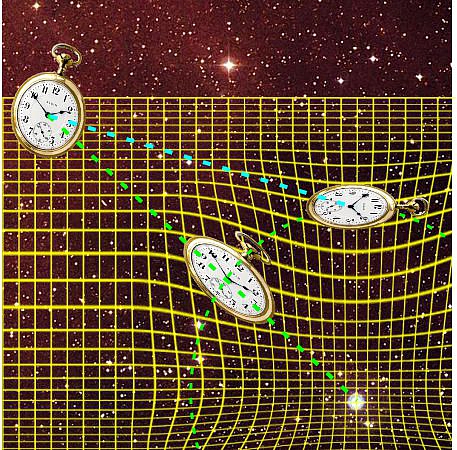

“Wait on. If they’re entangled and something happening to one instantaneously affects its twin, but the gravity difference gives each a different rate of time dilation, how does that work then?”

“Paradox, Jennie! That’s part of what the Firewall is about. But it gets worse. You’d think that inbound particle would add mass to the black hole, right?”

“Surely.”

“But it doesn’t. In fact, it reduces the object’s mass by exactly each particle’s mass. That ‘long-time zero average energy‘ rule comes into play here. If the two are separated and can’t annihilate, then one must have positive energy and the other must have negative energy. Negative energy means negative mass, because of Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence. The positive-mass twin escapes as Hawking radiation while the negative-mass twin joins the black hole, shrinks it, and by the way, increases its temperature.”

“Surely not, Sy. Temperature is average kinetic energy. Adding negative energy to something has to decrease its temperature.”

“Unless the something is a black hole, Jennie. Hawking showed that a black hole’s temperature is inversely dependent on its mass. Reduce the mass, raise the temperature, which is why a very small black hole radiates more intensely than a big one. Chalk up another paradox.”

“Two paradoxes. Negative mass makes no sense. I can’t make a pizza with negative cheese. People would laugh.”

“Right. Here’s another. Suppose you drop some highly-structured object, say a diamond, into a black hole. Sooner or later, much later really, that diamond’s mass-energy will be radiated back out. But there’s no relationship between the structure that went in and the randomized particles that come out. Information loss, which is totally forbidden by thermodynamics. Another paradox.”

“The Firewall resolves all these paradoxes then?”

“Not really, Jennie. The notion is that there’s this thin layer of insanely intense energetic interactions, the Firewall, just outside of the Event Horizon. That energy is supposed to break everything apart — entanglements, pre-existing structures, quantum propagators (don’t ask), everything, so what gets through the horizon is mush. Many physicists think that’s bogus and a cop-out.”

“So no Firewall Peril?”

“Wanna take the chance?”

~~ Rich Olcott

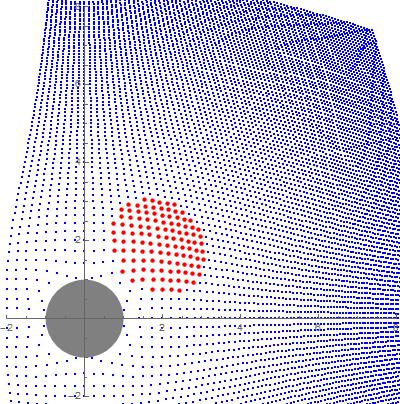

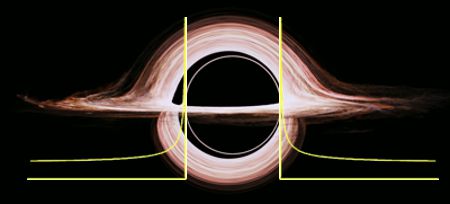

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

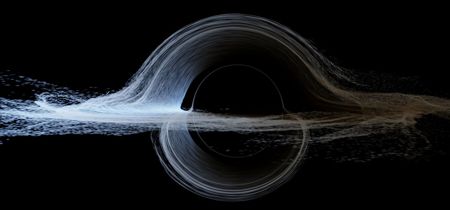

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”