Mr Feder just doesn’t quit. “But why did they make JWST so big? We’re getting perfectly good pictures from Hubble and it’s what, a third the size?”

Al’s brought over a fresh pot and he’s refilling our coffee mugs. “Chalk it up to good old ‘because we can.’ Rockets are bigger than in Hubble‘s day, robots can do more remote stuff by themselves, it all lets us make a bigger scope.”

Cathleen smiles. “There’s more to it than that, Al. It’s really about catching photons. You’re nearly correct, Mr Feder, the diameter ratio is 2.7. But photons aren’t captured by a line across the primary mirror, they’re captured by the mirror’s entire area. The important JSWT:Hubble ratio is between their areas. JWST beats Hubble there by a factor of 7.3. For a given source and the same time interval, we’d expect JWST to be that much more sensitive than Hubble.”

“Well,” I break in, “except that the two use photon detectors that are sensitive to different energy ranges. The two scopes often won’t even be looking at the same kinds of object. Hubble‘s specialized for visible and UV light. It’s easy to design detectors for that range because electrons in solid‑state devices respond readily to the high‑energy photons. The infrared light photons that JWST‘s designed for don’t have enough energy to kick electrons around the same way. Not really a fair comparison, although everything I’ve read says that JWST‘s sensitivity will be way up there.”

Mr Feder is derisive. “‘Way up there.’ Har, har, de-har. I suppose you’re proud of that.”

“Not really, it just happened. But Cathleen, I’m surprised that you as an astronomer didn’t bring up the other reason the designers went big for JWST.”

“True, but it’s more technical. You’re thinking of resolution and Rayleigh’s diffraction limit, aren’t you?”

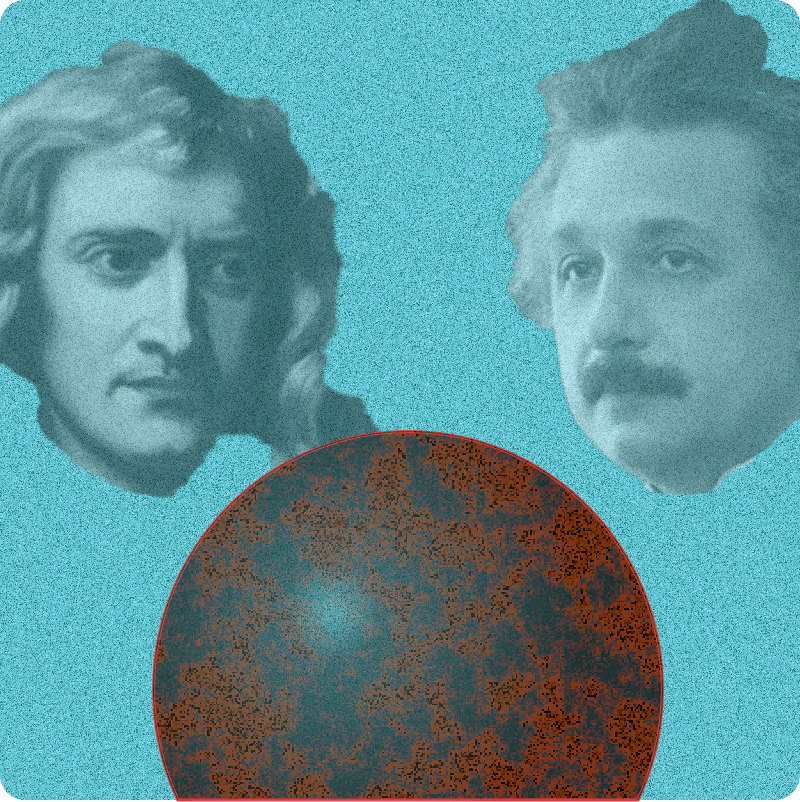

“Bingo. Except Rayleigh derived that limit from the Airy disk.”

“Disks in the air? We got UFOs now? What’re you guys talking about?”

licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International license.

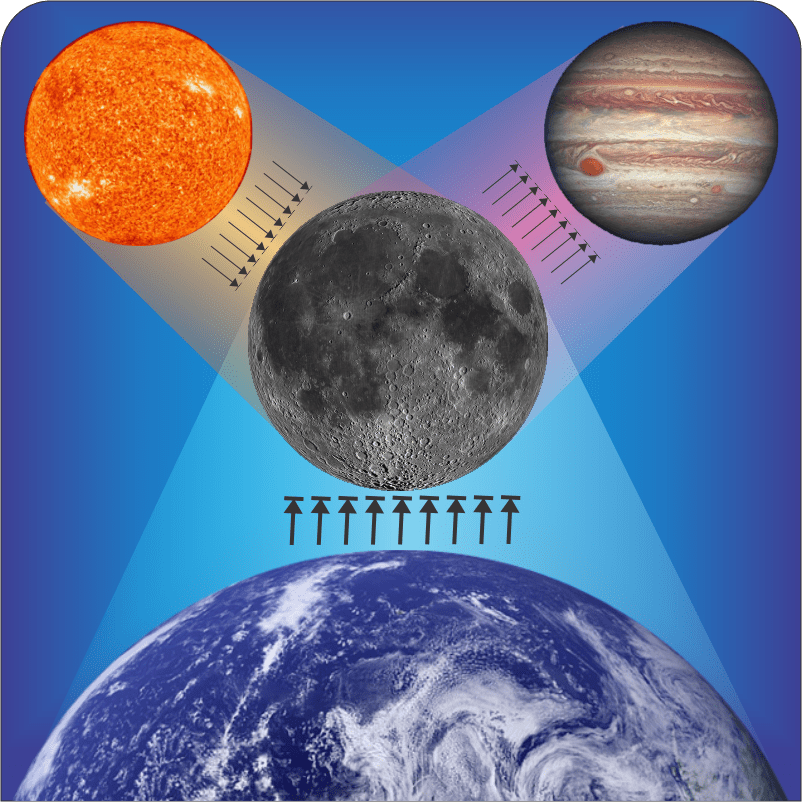

“No UFOs, Mr Feder, I’ll try to be non‑technical. Except for the big close objects like the Sun and its planets, telescopes show heavenly bodies as circular disks accompanied by faint rings. In the early 1800s an astronomer named George Airy proved that the patterns are an illusion produced by the telescope. His math showed that even the best possible apparatus will force lightwaves from any small distant light source to converge to a ringed circular disk, not a point. The disk’s size depends on the ratio between the light’s wavelength and the diameter of the telescope’s light‑gathering aperture. How am I doing, Al?”

“Fine so far.”

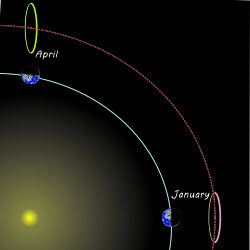

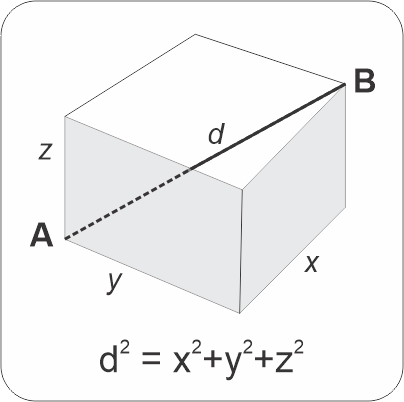

“Good. Rayleigh took that one step further. Suppose you’re looking at two stars that are very close together in the sky. You’d expect to see two Airy patterns. However, if the innermost ring from one star overlaps the other star’s disk, you can’t resolve the two images. That’s the basis for Rayleigh’s resolvability criterion — the angle between the star images, measured in arc‑seconds, has to be at least 252000 times the wavelength divided by the diameter.”

licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 International license.

“But blue light’s got a shorter wavelength than red light. Doesn’t that say that my scope can resolve close-together blue stars better than red stars?”

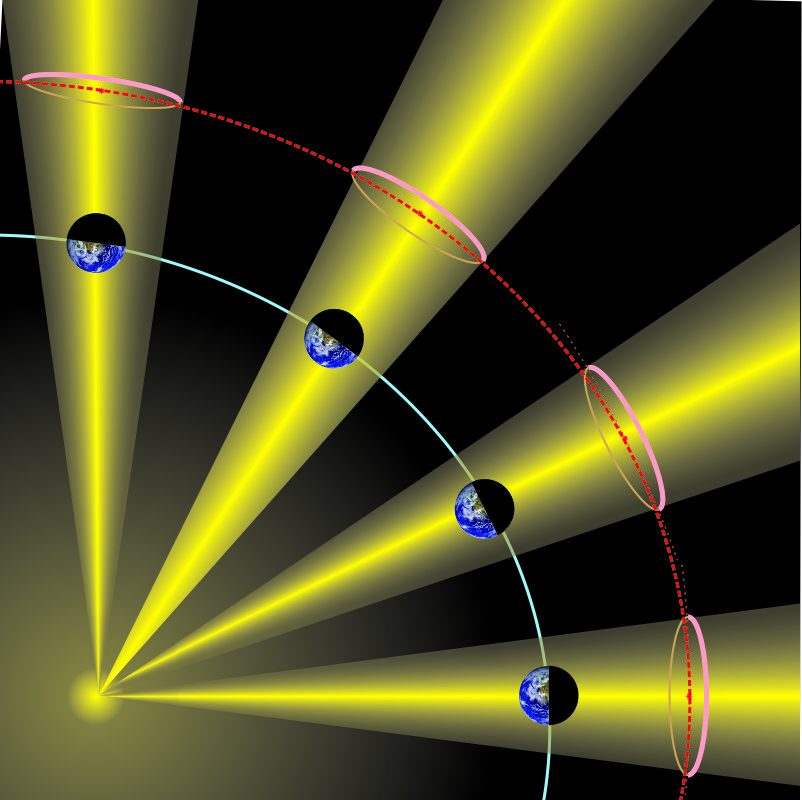

“Sure does, except stars don’t emit just one color. In visible light the disk and rings are all rimmed with reddish and bluish fuzz. The principle works just fine when you’re looking at a single wavelength. That gets me to the answer to Mr Feder’s question. It’s buried in this really elegant diagram I just happen to have on my laptop. Going across we’ve got the theoretical minimum angle for resolving two stars. Going up we’ve got aperture diameters, running from the pupil of your eye up to radio telescope coalitions that span continents. The colored diagonal bands are different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. The red bars mark each scope’s sensor wavelength range. Turns out JWST‘s size compared to Hubble almost exactly compensates for the longer wavelengths it reports on.”

~~ Rich Olcott