It’s getting nippy outside so Al’s moved his out‑front coffee cart into his shop. Jeremy’s manning the curbside take‑out window but I’m walking so I step inside. Limited seating, of course. “Morning, Al. Here’s my hiking mug, fill ‘er up with high‑test and I’ll take a couple of those scones — one orange, one blueberry. Good news that the Governor let you open up.”

“You know it, Sy. Me and my suppliers have been on the phone every day. Good thing we’ve got long‑term relationships and they’ve been willing to carry me but it gets on my conscience ’cause they’re in a crack, too, ya know?”

“Low velocity of money hurts everybody, Al. Those DC doofuses and their political kabuki … but don’t get me started. Hey, you’ve got a new poster over the cash register.”

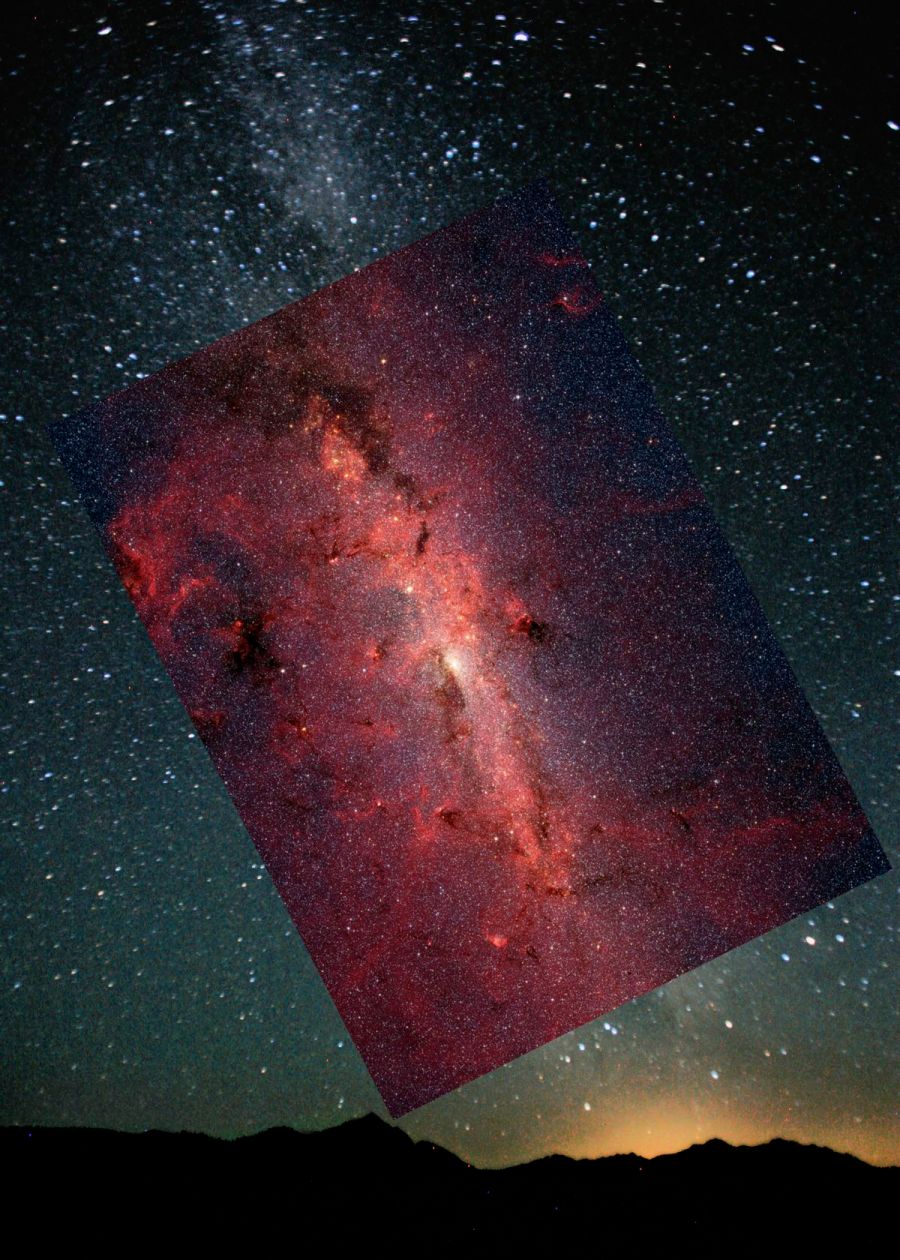

“You noticed. Yeah, it’s a beaut. Some artist’s idea of what it’d look like when a star gets spaghettified and eaten by a black hole. See, it’s got jets and a dust dusk and everything.”

“Very nice, except for a few small problems. That’s not spaghettification, the scale is all wrong and that tail-looking thing … no.”

Under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

“Not spaghettification? That’s what was in the headline.”

“Sloppy word choice. True spaghettification acts on solid objects. Gravity’s force increases rapidly as you approach the gravitational center. Suppose you’re in a kilometer-long star cruiser that’s pointing toward a black hole from three kilometers away. The cruiser’s tail is four kilometers out. Newton’s Law of Gravity says the black hole pulls almost twice as hard on the nose as on the tail. If the overall field is strong enough it’d stretch the cruiser like taffy. Larry Niven wrote about the effect in his short story, Neutron Star.”

“The black hole’s stretching the star, right?”

“Nup, because a star isn’t solid. It’s fluid, basically a gas held together by its own gravity. You can’t pull on a piece of gas to stretch the whole mass. Your news story should have said ‘tidal disruption event‘ but I guess that wouldn’t have fit the headline space. Anyhow, an atom in the star’s atmosphere is subject to three forces — thermal expansion away from any gravitational center, gravitational attraction toward its home star and gravitational attraction toward the black hole. The star breaks up atom by atom when the two bodies get close enough that the black hole’s attraction matches the star’s surface gravity. That’s where the scale problem comes in.”

Al looks around — no waiting customers so he strings me along. “How?”

“The supermassive black hole in the picture, AT2019qiz, masses about a million Suns‑worth. The Sun‑size star can barely hold onto a gas atom at one star‑radius from the star’s center. The black hole can grab that atom from a thousand star‑radii away, about where Saturn is in our Solar System. The artist apparently imagined himself to be past the star and about where Earth is to the Sun, 100 star‑radii further out. Perspective will make the black hole pretty small.”

“But that’s a HUGE black hole!”

“True, mass‑wise, not so much diameter‑wise. Our Sun’s about 864,000 miles wide. If it were to just collapse to a black hole, which it couldn’t, its Event Horizon would be about 4 miles wide. The Event Horizon of a black hole a million times as massive as the Sun would be less than 5 times as wide as the Sun. Throw in the perspective factor and that black circle should be less than half as wide as the star’s circle.”

“What about the comet‑tail?”

“The picture makes you think of a comet escaping outward but really the star’s material is headed inward and it wouldn’t be that pretty. The disruption process is chaotic and exponential. The star’s gravity weakens as it loses mass but the loss is lop‑sided. Down at the star’s core where the nuclear reactions happen the steady burn becomes an irregular pulse. The tail should flare out near the star. The rest should be jagged and lumpy.”

“And when enough gets ripped away…”

“BLOOEY!”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to T K Anderson for suggesting this topic.

- Link to Technical PS — Where Do Those Numbers Come From?.