<Cliff‑hanger Cathleen strikes again> “How can you even measure a 2‑million year half‑life?”

Kareem’s right back at her. “What’s a half‑life?”

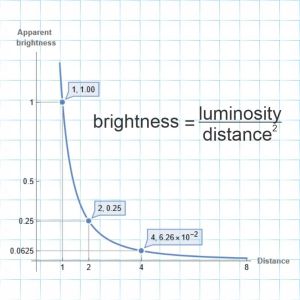

“Start a clock, weigh a sample, wait around for a while and then weigh it again to see how much is still there. When half of it’s gone, stop the clock and you’ve measured a half‑life. Simple.”

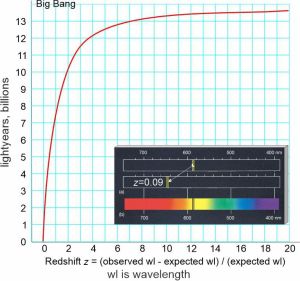

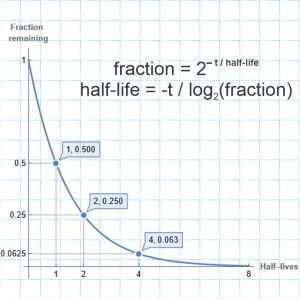

“Simple but not that simple or maybe a bit simpler. For one thing, you don’t have to wait for a full half‑life. For spontaneous radioactivity, all you have to know is the interval and whatever fraction disappeared. There’s a nice equation that ties those two to the half‑life.”

“Spontaneous? Like there’s another kind?”

“Stimulated radioactivity. That’s what nuclear reactors do — spew neutrons at uranium‑235 atoms, for instance, transmuting them to uranium‑236 so they’ll split into krypton and barium atoms and release energy and more neutrons. How often that happens depends on neutron concentration. Without that provoking push, the uranium nuclei would just split when they felt like it and that’s the natural half‑life.”

“Wait. I know that curve, it’s an exponential. Why isn’t e in the equation?”

“It could be. Would you prefer e-0.69315*t/half‑life? Works just as well but it’s clumsier. Base‑2 makes more sense when you’re talking halves. Usually when you say ‘exponential’ people visualize an increase. Here we’re looking at a decrease by a constant percentage rate but yeah, that’s an exponential, too. You get a falling curve like that from a Geiger counter and you’re watching counts per minute from someone’s thyroid that’s been treated with iodine‑131. Its 8‑day half‑life is slow enough to track that way. Really short half‑lives I don’t know much about; I care about the slow disintegraters that are either primordial or generated by some process.”

“Primordial — that means ‘back to the beginning’, which in your specialty would mean the beginning of the Solar System. We’re pretty sure the Sun’s pre‑planetary disk was built from dust broadcast by stars that went nova. Isotopes in the dust must be the primordial isotopes, right? Which ones are the other kind?”

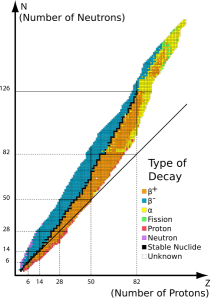

“Mmm, aluminum‑26 is a good example. The half‑life equation still applies even for million‑year intervals. Half‑life of aluminum‑26 is about 0.7 million years and it decays to magnesium‑26. Whatever amount got here from the stars would have burnt down to a trillionth of that within the first 30 million years or so after arrival. Any aluminum‑26 we find today couldn’t be primordial. On the other hand, cosmic rays can smack a proton and neutron out of a silicon‑28 nucleus and voila! a new aluminum‑26. There’s a steady rain of cosmic rays out in space so there’s a steady production of aluminum‑26 out there. Not here on Earth, though, because our atmosphere blocks out most of the rays. Very nice for us geologists who can compare measured aluminum‑26 to excess magnesium‑26 to determine when a meteorite fell.”

“Excess?”

“Background magnesium is about 10% magnesium‑26 so we have subtract that to get the increment which came from aluminum‑26. A lot of the arguments in our field hinge on how much of which isotope is background or was background when a given rock formed. That’s one reason you see so much press about tiny but rugged zircons. They’re key to uranium‑lead dating. Crystallizing zirconium silicate doesn’t allow lead ions into its structure but it happily incorporates uranium ions. Uranium‑235 and uranium‑238 both decay to crystal‑trapped lead, but each isotope goes to a different lead isotope and with a different half‑life. The arithmetic’s simpler and the results are more definitive when you know that the initial lead content was zero.”

“So that aluminum‑magnesium trick’s not your only tool?”

“Hardly. The nuclear chemists have given us a long list of isotope chains, what decays to what with what half‑life and how much energy the radiating particle gets. Nuclei flit between quantum energy levels just like atoms and molecules do, except a spectrum of alpha or beta particles is a different game from the light‑wave spectrum. Tell me a radiated particle’s energy and I can probably tell you which isotope spat it out and disappeared.”

“Your ladder rungs are Cheshire Cat grins.”

~~ Rich Olcott