An excited knock, but one I recognize. In comes Vinnie, waving his fresh copy of The New York Times.

“LIGO‘s done it again! They’ve seen another black hole collision!”

“Yeah, Vinnie, I’ve read the Abbott-and-a-thousand paper. Three catastrophic collisions detected in less than two years. The Universe is starting to look like a pretty busy place, isn’t it?”

“And they all involve really big black holes — 15, 20, even 30 times heavier than the Sun. Didn’t you once say black holes that size couldn’t exist?”

“Well, apparently they do. Of course the physicists are busily theorizing how that can happen. What do you know about how stars work, Vinnie?”

“They get energy from fusing hydrogen atoms to make helium atoms.”

“So far, so good, but then what happens when the hydrogen’s used up?”

“They go out, I guess.”

“Oh, it’s a lot more exciting than that. Does the fusion reaction happen everywhere in the star?”

“I woulda said, ‘Yes,’ but since you’re asking I’ll bet the answer is, ‘No.'”

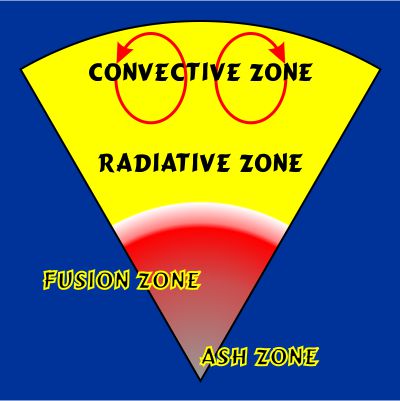

“Properly suspicious, and you’re right. It takes a lot of heat and pressure to force a couple of positive nuclei close enough to fuse together despite charge repulsion. Pressures near the outer layers are way too low for that. For our Sun, for instance, you need to be 70% of the way to the center before fusion really kicks in. So you’ve got radiation pressure from the fusion pushing everything outward and gravity pulling everything toward the center. But what’s down there? Here’s a hint — hydrogen’s atomic weight is 1, helium’s is 4.”

“You’re telling me that the heavier atoms sink to the center?”

“I am.”

“So the center builds up a lot of helium. Oh, wait, helium atoms got two protons in there so it’s got to be harder to mash them together than mashing hydrogens, right?”

“And that’s why that region’s marked ash zone in this sketch. Wherever conditions are right for hydrogen fusion, helium’s basically inert. Like ash in a campfire it just sinks out of the way. Now the fire goes out. What would you expect next?”

“Radiation pressure’s gone but gravity’s still there … everything must slam inwards.”

“Slam is an excellent word choice, even though the star’s radius is measured in thousands of miles. What’s the slam going to do to the helium atoms?”

“Is it strong enough to start helium fusion?”

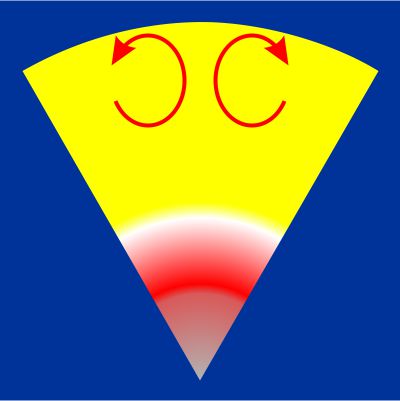

“That’s where I’m going. The star starts fusing helium at its core. That’s a much hotter reaction than hydrogen’s. When convective zone hydrogen that’s still falling inward meets fresh outbound radiation pressure, most of the hydrogen gets blasted away.”

“Fusing helium – that’s a new one on me. What’s that make?”

“Carbon and oxygen, mostly. They’re as inert during the helium-fusion phase as helium was when hydrogen was doing its thing.”

“So will the star do another nova cycle?”

“Maybe. Depends on the core’s mass. Its gravity may not be intense enough to fuse helium’s ashes. In that case you wind up with a white dwarf, which just sits there cooling off for billions of years. That’s what the Sun will do.”

“But suppose the star’s heavy enough to burn those ashes…”

“The core’s fresh light-up blows away infalling convective zone material. The core makes even heavier atoms. Given enough fuel, the sequence repeats, cycling faster and faster until it gets to iron. At each stage the star has less mass than before its explosion but the residual core is more dense and its gravity field is more intense. The process may stop at a neutron star, but if there was enough fuel to start with, you get a black hole.”

“That’s the theory that accounts for the Sun-size black holes?”

“Pretty much. I’ve left out lots of details, of course. But it doesn’t account for black holes the size of 30 Suns — really big stars go supernova and throw away so much of their mass they miss the black-hole sweet spot and terminate as a neutron star or white dwarf. That’s where the new LIGO observation comes in. It may have clued us in on how those big guys happen.”

“That sketch looks like a pizza slice.”

“You’re thinking dinner, right?”

“Yeah, and it’s your turn to buy.”

~~ Rich Olcott

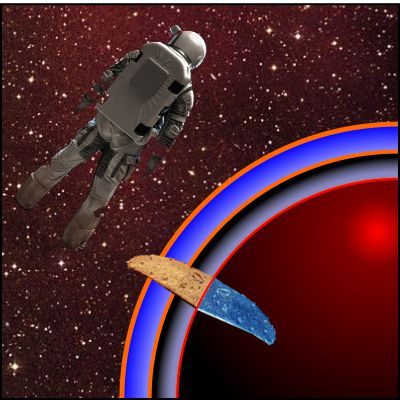

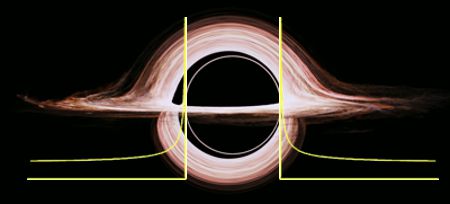

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”