I heard a familiar squeak from the floorboard outside my office.

“C’mon in, Vinnie, the door’s open. What can I do for you?”

“I still got problems with LIGO. I get that dark energy and cosmic expansion got nothin’ to do with it. But you mentioned inertial frame and what’s that about?”

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Huh? Depends on where you are, I guess.”

“Well, there you are.”

“Waitaminnit! That can’t be all there is to it!”

“You’re right, there’s more. It all goes back to Newton’s First Law.” (showing him my laptop screen) “Here’s how Wikipedia puts it in modern terms…”

In an inertial reference frame, an object either remains at rest or continues to move at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by a net force.

“That’s really a definition rather than a Law. If you’re looking at an object and it doesn’t move relative to you or else it’s moving at constant speed in a straight line, then you and the object share the same inertial frame. If it changes speed or direction relative to you, then it’s in a different inertial frame from yours and Newton’s Laws say that there must be some force that accounts for the difference.”

“So another guy’s plane flying straight and level with me has a piece of my inertial frame?”

“Yep, even if you’re on different vectors. You only lose that linkage if either airplane accelerates or curves off.”

“So how’s that apply to LIGO’s laser beams? I thought light always traveled in straight lines.”

“It does, but what’s a straight line?”

“Shortest distance between two points — I been to flight school, Sy.”

“Fine. So if you fly from London to Mexico City on this globe here you’d drill through the Earth?”

“Of course not, I’d take the Great Circle route that goes through those two cities. It’s the shortest flight path. Hey, how ’bout that, the circle goes through NYC and Atlanta, too.”

“Cool observation, but that line looks like a curve from where I sit.”

“Yeah, but you’re not sittin’ close to the globe’s surface. I gotta fly in the flight space I got.”

“So does light. Photons always take the shortest available path, though sometimes that path looks like a curve unless you’re on it, too. Einstein predicted that starlight passing through the Sun’s gravitational field would be bent into a curve. Three years later, Eddington confirmed that prediction.”

“Light doesn’t travel in a straight line?”

“It certainly does — light’s path defines what is a straight line in the space the light is traveling through. Same as your plane’s flight path defines that Great Circle route. A gravitational field distorts the space surrounding it and light obeys the distortion.”

“You’re getting to that ‘inertial frames’ stuff, aren’t you?”

“Yeah, I think we’re ready for it. You and that other pilot are flying steady-speed paths along two navigation beams, OK?”

“Navigation beams are radio-frequency.”

“Sure they are, but radio’s just low-frequency light. Stay with me. So the two of you are zinging along in the same inertial frame but suddenly a strong gravitational field cuts across just your beam and bends it. You keep on your beam, right?”

“I suppose so.”

“And now you’re on a different course than the other plane. What happened to your inertial frame?”

“It also broke away from the other guy’s.”

“Because you suddenly got selfish?”

“No, ’cause my beam curved ’cause the gravity field bent it.”

“Do the radio photons think they’re traveling a bent path?”

“Uh, no, they’re traveling in a straight line in a bent space.”

“Does that space look bent to you?”

“Well, I certainly changed course away from the other pilot’s.”

“Ah, but that’s referring to his inertial frame or the Earth’s, not yours. Your inertial frame is determined by how those photons fly, right? In terms of your frame, did you peel away or stay on-beam?”

“OK, so I’m on-beam, following a straight path in a space that looks bent to someone using a different inertial frame. Is that it?”

“You got it.”

(sounds of departing footsteps and closing door)

“Don’t mention it.”

~~ Rich Olcott

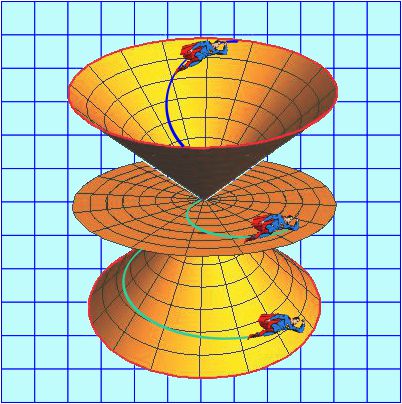

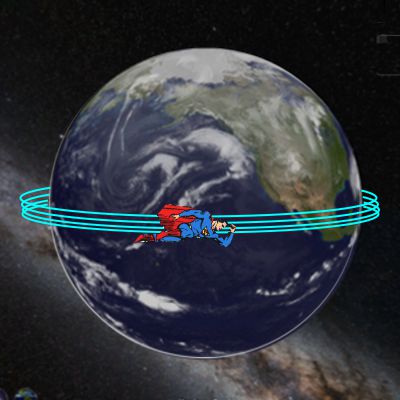

But for this post let’s consider a trope that’s been taken off the shelf again and again since those days, even in the movies. This rendition should get the idea across — Our Hero, in a desperate effort to fix a narrative hole the writers had dug themselves into, is forced to fly around the Earth at faster-than-light speeds, thereby reversing time so he can patch things up.

But for this post let’s consider a trope that’s been taken off the shelf again and again since those days, even in the movies. This rendition should get the idea across — Our Hero, in a desperate effort to fix a narrative hole the writers had dug themselves into, is forced to fly around the Earth at faster-than-light speeds, thereby reversing time so he can patch things up.

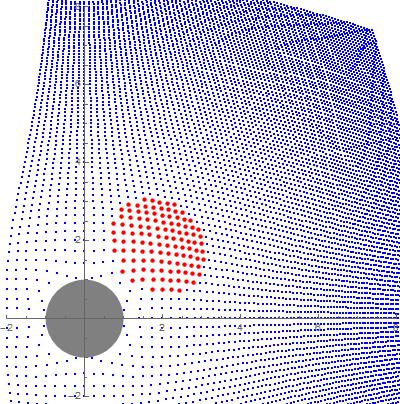

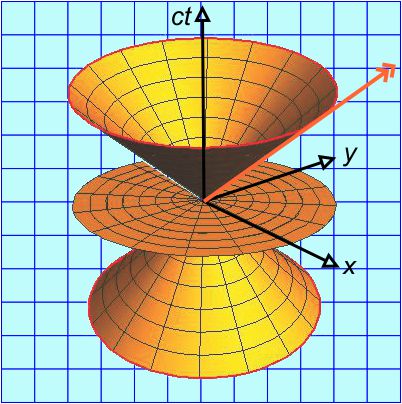

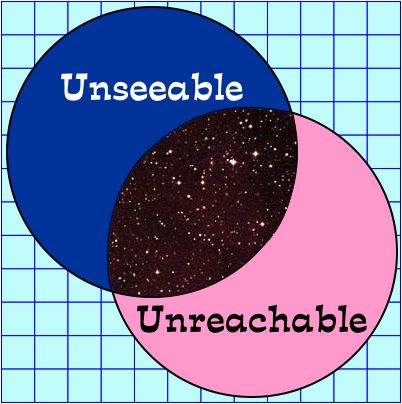

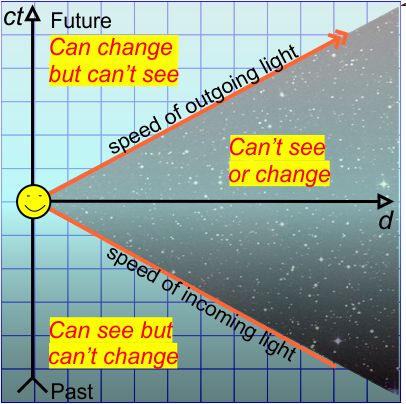

The rest of the Minkowski diagram could do for a Venn diagram. We at (0,0,0,0) can do something that will cause something to happen at (ct,x,y,z) to the left of the top orange line. However, we won’t be able to see that effect until we time-travel forward to its t. That region is “reachable but not seeable.”

The rest of the Minkowski diagram could do for a Venn diagram. We at (0,0,0,0) can do something that will cause something to happen at (ct,x,y,z) to the left of the top orange line. However, we won’t be able to see that effect until we time-travel forward to its t. That region is “reachable but not seeable.”

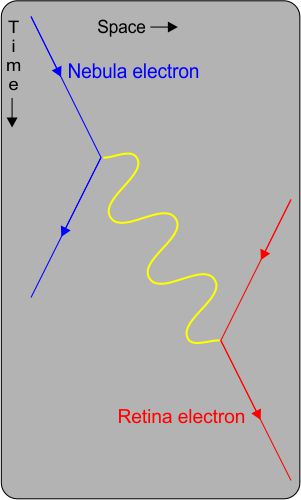

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

Sure enough, that’s a straight line (see the chart). Reminds me of how Newton’s Law of Gravity is valid

Sure enough, that’s a straight line (see the chart). Reminds me of how Newton’s Law of Gravity is valid