“Sis, you say there’s dessert?”

“Of course there is, Sy. Teena, please bring in the tray from the fridge.”

“Tiramisu! You did indeed go above and beyond. Thank you, Teena. Your Mom’s question must be a doozey.”

“I’ll let you enjoy a few spoonfulls before I hit you with it.” <minutes with spoon noises and yumming> “Okay. tell me about entanglement.”

“Whoa! What brought that on?”

“I’ve seen the word bandied about in the popular science press—”

“And pseudoscience—”

“Well, yes. I’m writing something where the notion might come in handy if it makes sense.”

“How can you tell what’s pseudoscience?”

“Good question, Teena. I look for gee-whiz sentences, especially ones that include weasely words like ‘might‘ and ‘could.’ Most important, does the article make or quote big claims that can’t be disproven? I’d want to see pointers to evidence strong enough to match the claims. A respectable piece would include comments from other people working in the same field. Things like that.”

“What your Mom said, and also has the author used a technical term like ‘energy‘ or ‘quantum‘ but stretched it far away from its home base? Usually when they do that and you have even an elementary idea what the term really means, it’s pretty clear that the author doesn’t understand what they’re writing about. That goes double for a lot of what you’ll see on YouTube and social media in general. It’s just so easy to put gibberish up there because there’s no‑one to contradict a claim, or if there is, it’s too late because the junk has already spread. ‘Entanglement‘ is just the latest buzzword to join the junk‑science game.”

“So what can you tell us about entanglement that’s non‑junky?”

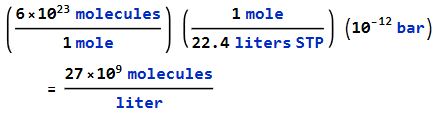

“First thing is, it’s strictly a microscopic phenomenon, molecule‑tiny and smaller. Anything you read about people or gemstones being entangled, you can stop reading right there unless it’s for fun.”

“Weren’t Rapunzel and the prince entangled?

“They and all the movie’s other characters were tangled up in the story, yes, but that’s not the kind of entanglement your Mom’s asking about. This kind seems to involve something that Einstein called ‘spooky action at a distance‘. He didn’t like it.”

“‘Seems to‘?”

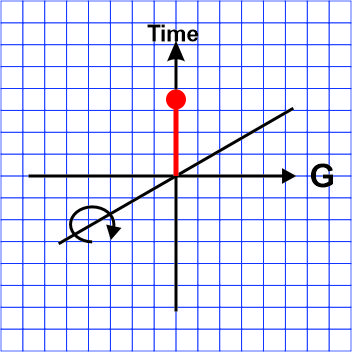

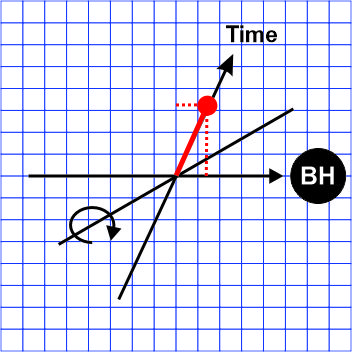

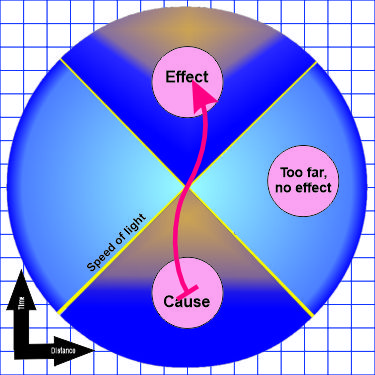

“Caught me, Sis, but it’s an important point. You make a system do something by acting on it, right? We’re used to actions where force is transmitted by direct contact, like hitting a ball with a bat. We’ve known how direct contact works with solids and fluids since Newton. We’ve extended the theory to indirect contact via electric and other fields thanks to Maxwell and Einstein and a host of other physicists. ‘Action at a distance‘ is about making something happen without either direct or indirect contact and that’s weird.”

“Can you give us an example?”

“How about an entanglement story? Suppose there’s a machine that makes coins, nicely packaged up in gift boxes. They’re for sweethearts so it always makes the coins in pairs, one gold and one silver. These are microscopic coins so quantum rules apply — every coin is half gold and half silver until its box is opened, at which point it becomes all one pure metal.”

“Like Schrödinger’s asleep‑awake kitty‑cat!”

“Exactly, Teena. So Bob buys a pair of boxes, keeps one and gives the other to Alice before he flies off in his rocket to the Moon. Quantum says both coins are both metals. When he lands, he opens his box and finds a silver coin. What kind of coin does Alice have?”

“Gold, of course.”

“For sure. Bob’s coin‑checking instantly affected Alice’s coin a quarter‑million miles away. Spooky, huh?”

“But wait a minute. Alice’s coin doesn’t move. It’s not like Bob pushed on it or anything. The only thing that changed was its composition.”

“Sis, you’ve nailed it. That’s why I said ‘seems to‘. Entanglement’s not really action at a distance. No energy or force is exerted, it’s simply an information thing about quantum properties. Which, come to think of it, is why there’s no entanglement of people or gemstones. Even a bacterium has billions and billions of quantum‑level properties. Entanglement‑tweaking one or two or even a thousand atoms won’t affect the object as a whole.”

~~ Rich Olcott