“Minus? Where did that come from?”

<Gentle reader — If that question looks unfamiliar, please read the preceding post before this one.>

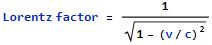

Jim’s still at the Open Mic. “A clever application of hyperbolic geometry.” Now several of Jeremy’s groupies are looking upset. “OK, I’ll step back a bit. Jeremy, suppose your telescope captures a side view of a 1000‑meter spaceship but it’s moving at 99% of lightspeed relative to you. The Lorentz factor for that velocity is 7.09. What will its length look like to you?”

“Lorentz contracts lengths so the ship’s kilometer appears to be shorter by that 7.09 factor so from here it’d look about … 140 meters long.”

“Nice, How about the clocks on that spaceship?”

“I’d see their seconds appear to lengthen by that same 7.09 factor.”

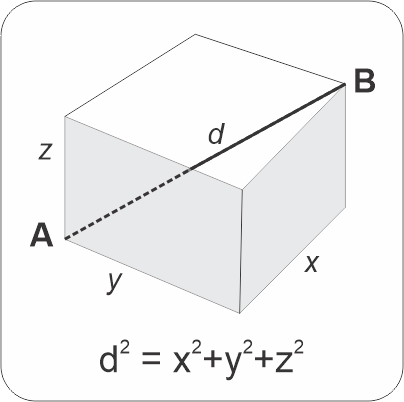

“So if I multiplied the space contraction by the time dilation to get a spacetime hypervolume—”

“You’d get what you would have gotten with the spaceship standing still. The contraction and dilation factors cancel out.”

“How about if the spaceship went even faster, say 99.999% of lightspeed?”

“The Lorentz factor gets bigger but the arithmetic for contraction and dilation still cancels. The hypervolume you defined is always gonna be just the product of the ship’s rest length and rest clock rate.”

His groupies go “Oooo.”

One of the groupies pipes up. “Wait, the product of x and y is a constant — that’s a hyperbola!”

“Bingo. Do you remember any other equations associated with hyperbolas?”

“Umm… Yes, x2–y2 equals a constant. That’s the same shape as the other one, of course, just rotated down so it cuts the x-axis vertically.”

Jeremy goes “Oooo.”

Jim draws hyperbolas and a circle on the whiteboard. That sets thoughts popping out all through the crowd. Maybe‑an‑Art‑major blurts into the general rumble. “Oh, ‘plus‘ locks x and y inside the constant so you get a circle boundary, but ‘minus‘ lets x get as big as it wants so long as y lags behind!”

Another conversation – “Wait, can xy=constant and x2–y2=constant both be right?”

”Sure, they’re different constants. Both equations are true where the red and blue lines cross.”

A physics student gets quizzical. “Jim, was this Minkowski’s idea, or Einstein’s?”

“That’s a darned good question, Paul. Minkowski was sole author of the paper that introduced spacetime and defined the interval, but he published it a year after Einstein’s 1905 Special Relativity paper highlighted the Lorentz transformations. I haven’t researched the history, but my money would be on Einstein intuitively connecting constant hypervolumes to hyperbolic geometry. He’d probably check his ideas with his mentor Minkowski, who was on the same trail but graciously framed his detailed write‑up to be in support of Einstein’s work.”

One of the astronomy students sniffs. “Wait, different observers see the same s2=(ct)2–d2 interval between two events? I suppose there’s algebra to prove that.”

“There is.”

“That’s all very nice in a geometric sort of way, but what does s2 mean and why should we care whether or not it’s constant?”

“Fair questions, Vera. Mmm … you probably care that intervals set limits on what astronomers see. Here’s a Minkowski map of the Universe. We’re in the center because naturally. Time runs upwards, space runs outwards and if you can imagine that as a hypersphere, go for it. Light can’t get to us from the gray areas. The red lines, they’re really a hypercone, mark where s2=0.”

From the back of the room — “A zero interval?”

“Sure. A zero interval means that the distance between two events exactly equals lightspeed times light’s travel time between those events. Which means if you’re surfing a lightwave between two events, you’re on an interval with zero measure. Let’s label Vera’s telescope session tonight as event A and her target event is B. If the A–B interval’s ct difference is greater then its d difference then she can see B — if the event is in our past but not beyond the Cosmic Microwave Background. But if a Dominion fleet battle is approaching us through subspace from that black dot, we’ll have no possible warning before they’re on us.”

Everyone goes “Oooo.”

~~ Rich Olcott