A warmish Spring day. I’m under a shady tree by the lake, waiting for the eclipse and doing some math on Old Reliable. Suddenly there’s a text‑message window on its screen. The header bar says 710‑555‑1701 . Old Reliable has never held a messaging app, that’s not what I use it for, but the set-up is familiar. I type in, Hello?

Hello, Mr Moire. Remember me?

Of course I do. That sultry knowing stare, those pointed ears. Hello, Lieutenant Baird. It’s been a year. What can I do for you?

Not Lieutenant any more, I’m back up to Commander, Provisional.

Congratulations. Did you invent something again?

Yes, but I can’t discuss it on this channel. I owe you for the promotion. I got the idea from one of your Crazy Theories posts. You and your friends have no clue but you come up with interesting stuff anyway.

You’re welcome, I suppose. Mind you, your science is four centuries ahead of ours but we do the best we can.

I know that, Mr Moire. Which is why I’m sending you this private chuckle.

Private like with Ralphie’s anti‑gravity gadget? I suggested he add another monitoring device in between two of his components. That changed the configuration you warned me about. He’s still with us, no anti‑gravity, but now he blames me.

Good ploy. Sorry about the blaming. Now it’s your guy Vinnie who’s getting close to something.

Vinnie? He’s not the inventor type, except for those maps he’s done with his buddy Larry. What’s he hit on?

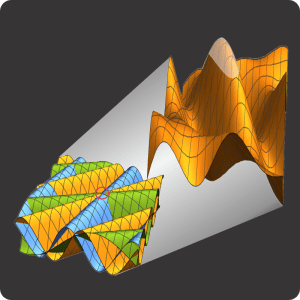

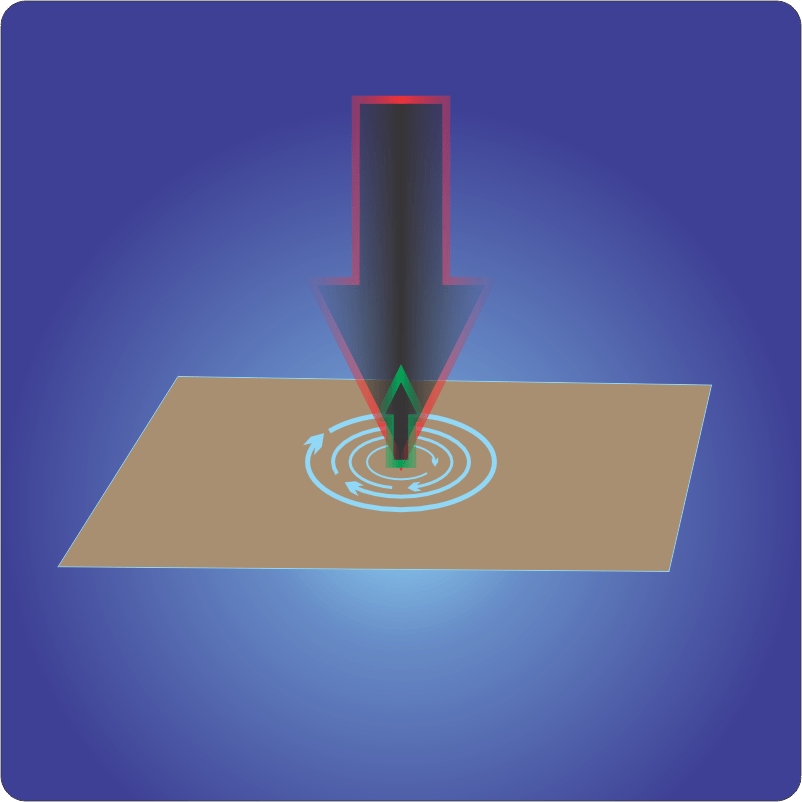

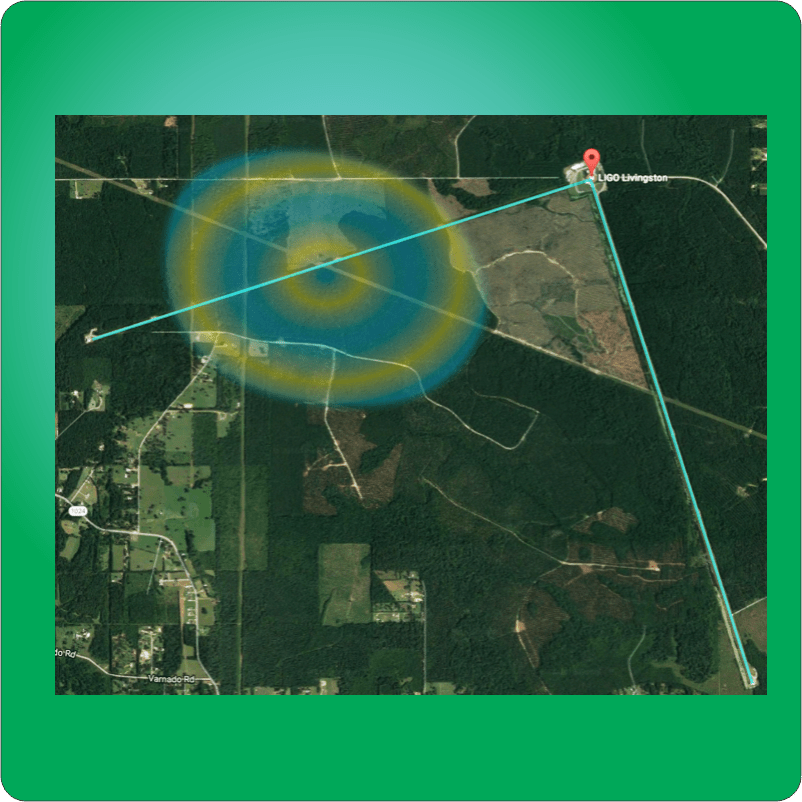

His speculation from your Quantum Field Theory discussion that entanglement is somehow involved with ripples in a QFT field, ripples that are too weak to register as a particle peak. He’s completely backwards on entanglement, but those ripples—

Wait, what’s that about entanglement?

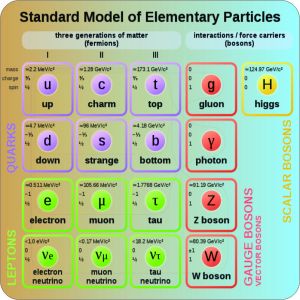

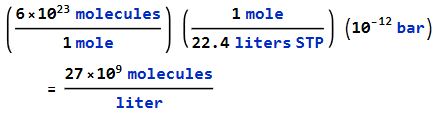

Entanglement is the normal state for quantized particles. Our 24th‑Century science says every real and virtual particle in the Universe is entangled with every other particle that shares the same fields. It’s an all‑embracing quantum state. Forget your reductionist 20th‑Century‑style quantum states, this is something … different. Your Hugh Everett and his mentor John Archibald Wheeler had an inking of that fact a century before your time, though of course they didn’t properly understand the implications and drew a ridiculous conclusion. Anyway, when your experimenting physicists say they’ve created an entangled particle pair, they’ve simply extracted two particles from the common state. When they claim to transmit one of the particles somewhere they’re really damping out the local field peak linked to their particle’s anti‑particle’s anti‑peak at the distant location and that puts an anti‑anti‑particle‑particle peak there. Naturally, that happens nearly instantaneously.

I don’t follow the anti‑particle‑anti‑peak part. Or why it’s naturally instantaneous.

I didn’t expect you to or else I wouldn’t have told you about it. The Prime Directive, you know. Which is why the chuckle has to be private, understand?

I won’t tell. I live in “the city that knows how to keep its secrets,” remember?

Wouldn’t do you any good if you did tell and besides, Vinnie wouldn’t think it’s funny. Here’s the thing. As Vinnie guessed, there are indeed sub‑threshold ripples in all of the fundamental fields that support subatomic particles and the forces that work between them. And no, I won’t tell you how many fields, your Standard Model has quite enough complexity to <heh> perturb your physicists. A couple hundred years in your future, humanity’s going to learn how to manipulate the quarks that inhabit the protons and neutrons that make up a certain kind of atom. You’ll jiggle their fields and that’ll jiggle other fields. Pick the right fields and you get ripples that travel far away in space but very little in time, almost horizontal in Minkowski space. It won’t take long for you to start exploiting some of your purposely jiggled fields for communication purposes. Guess what a lovely anachronism you’ll use to name that capability.

‘Jiggled fields’ sounds like communications tech we use today based on the electromagnetic field — light waves traveling through glass fibers, microwave relays for voice and data—

You’re getting there. Go for the next longer wavelength range.

Radio? You’ll call it radio?

Subspace radio. Isn’t that wonderful?

~~ Rich Olcott