Suddenly there’s a hubbub of girlish voices to one side of the crowd. “Go on, Jeremy, get up there.” “Yeah, Jeremy, your theory’s no crazier than theirs.” “Do it, Jeremy.”

Sure enough, the kid’s here with some of his groupies. Don’t know how he does it. He’s a lot younger than the grad students who generally present at these contests, but he’s got guts and he grabs the mic.

“OK, here’s my Crazy Theory. The Solar System has eight planets going around the Sun, and an oxygen atom has eight electrons going around the nucleus. Maybe we’re living in an oxygen atom in some humongous Universe, and maybe there are people living on the electrons in our oxygen atoms or whatever. Maybe the Galaxy is like some huge molecule. Think about living on an electron in a uranium atom with 91 other planets in the same solar system and what happens when the nucleus fissions. Would that be like a nova?”

There’s a hush because no-one knows where to start, then Cathleen’s voice comes from the back of the room. Of course she’s here — some of the Crazy Theory contest ring-leaders are her Astronomy students. “Congratulations, Jeremy, you’ve joined the Honorable Legion of Planetary Atom Theorists. Is there anyone in the room who hasn’t played with the idea at some time?”

No-one raises a hand except a couple of Jeremy’s groupies.

“See, Jeremy, you’re in good company. But there are a few problems with the idea. I’ll start off with some astronomical issues and then the physicists can throw in some more. First, stars going nova collapse, they don’t fission. Second, compared to the outermost planet in the Solar System, how far is it from the Sun to the nearest star?”

A different groupie raises her hand and a calculator. “Neptune’s about 4 light-hours from the Sun and Alpha Centauri’s a little over 4 light-years, so that would be … the 4’s cancel, 24 hours times 365 … about 8760 times further away than Neptune.”

“Nicely done. That’s a typical star-to-star distance within the disk and away from the central bulge. Now, how far apart are the atoms in a molecule?”

“Aren’t they pretty much touching? That’s a lot closer than 8760 times the distance.”

“Yes, indeed, Jeremy. Anyone else with an objection? Ah, Maria. Go ahead.”

“Yes, ma’am. All electrons have exactly the same properties, ¿yes? but different planets, they have different properties. Jupiter is much, much heavier than Earth or Mercury.”

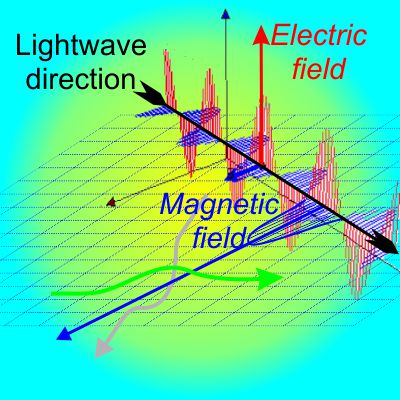

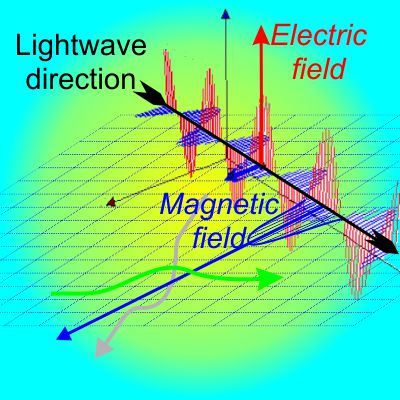

Astrophysicist-in-training Jim speaks up. “Different force laws. Solar systems are held together by gravity but at this level atoms are held together by electromagnetic forces.”

“Carry that a step further, Jim. What does that say about the geometry?”

“Gravity’s always attractive. The planets are attracted to the Sun but they’re also attracted to each other. That’ll tend to pull them all into the same plane and you’ll get a flat disk, mostly. In an atom, though, the electrons or at least the charge centers repel each other — four starting at the corners of a square would push two out of the plane to form a tetrahedron, and so forth. That’s leaving aside electron spin. Anyhow, the electronic charge will be three-dimensional around the nucleus, not planar. Do you want me to go into what a magnetic field would do?”

“No, I think the point’s been made. Would someone from the Physics side care to chime in?”

“Synchrotron radiation.”

“Good one. And you are …?”

“Newt Barnes. I’m one of Dr Hanneken’s students.”

“Care to explain?”

“Sure. Assume a hydrogen atom is a little solar system with one electron in orbit around the nucleus. Any time a charge moves it radiates waves into the electromagnetic field. The waves carry forces that can compel other charged objects to move. The distance an object moves, times the force exerted, equals the amount of energy expended by the wave. Therefore the wave must carry energy and that energy must have come from the electron’s motion. After a while the electron runs out of kinetic energy and falls into the nucleus. That doesn’t actually happen, so the atom’s not a solar system.”

Jeremy gets general applause when he waves submission, then the crowd’s chant resumes…

.——<“Amanda! Amanda! Amanda!”>

~~ Rich Olcott

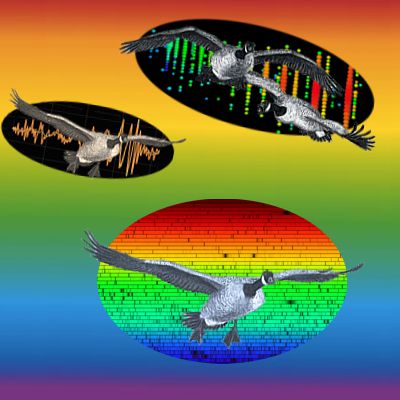

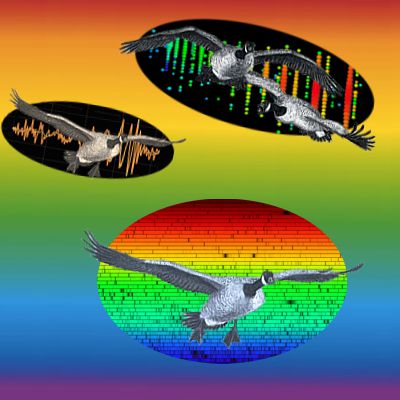

“Thanks, Sy. Look, we’ve got three intervals where everything syncs up. See the new satellite peaks half-way in between? There’s more hidden pattern where things look chaotic in the rest of the space.”

“Thanks, Sy. Look, we’ve got three intervals where everything syncs up. See the new satellite peaks half-way in between? There’s more hidden pattern where things look chaotic in the rest of the space.”

“Why should there be flashes? I thought neutrinos didn’t interact with matter.”

“Why should there be flashes? I thought neutrinos didn’t interact with matter.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

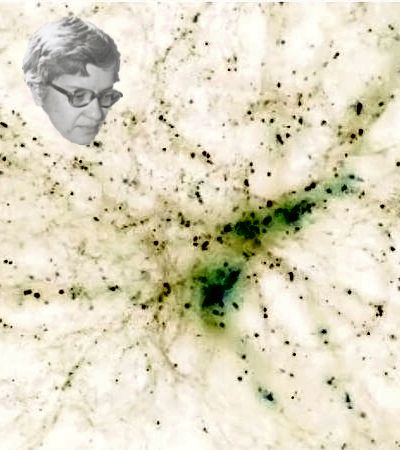

“Not much. We can’t see it, and they say there is much more of it than the matter we can see. If we can’t see it, how did she find it? That’s a thing I don’t understand, what I came to your office to ask.”

“Not much. We can’t see it, and they say there is much more of it than the matter we can see. If we can’t see it, how did she find it? That’s a thing I don’t understand, what I came to your office to ask.”

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by

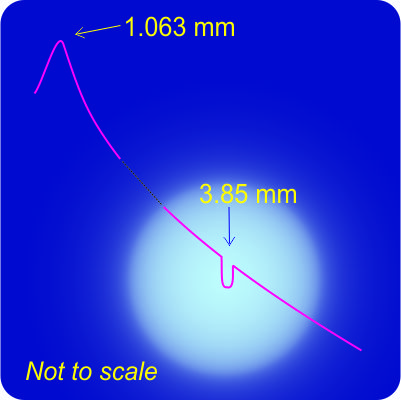

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by  Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

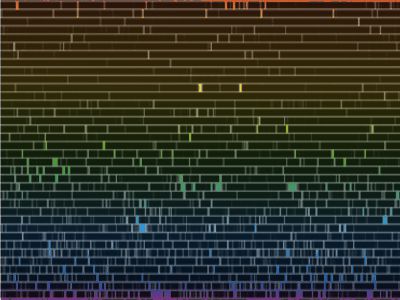

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”